University budgets are moral documents

Universities are creating a(n intentional) recursive doom loop for the Humanities

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

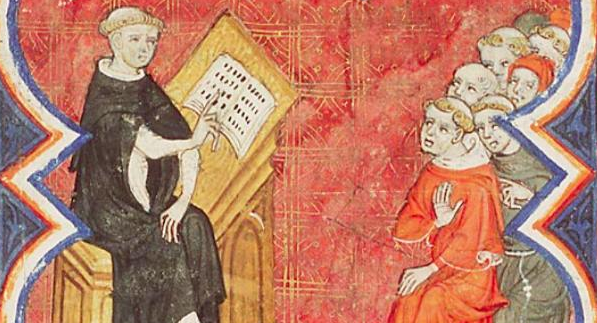

The university is one of the foremost legacies of the Middle Ages, developing into a formal institution from various other modes of instruction into the something very close to what we know today. This happened for three main reasons: First and most importantly, faculty and students wanted power to resist outside (political and social) control over what was taught. Second (and not unrelated), medieval European students got into a lot of bar fights with townies and wanted protection from consequences. History ain't all glamorous. And third (also related), faculty wanted the right to organize themselves - "university" comes from the Latin "universitas" and means, originally, "community" - and this meant, at least in part, control over the money.

We are in a tough moment for the Humanities generally and the discipline of History in particular (and Medieval European History in even more particular). It's true that this crisis has been felt for a long time, but the data seems to show that it got worse around 2016, hasn't improved, and has led to a related collapse in hiring in the tenure-track job market.

There are lots of reasons for this collapse, but even if the more typical responses - we need historians, history majors get jobs, humanities are good for society - are important, perhaps we need to begin thinking a bit differently about this all. Making arguments about culture, ideas, even outcomes, is overlooking the ways that universities use budget distribution models and other administrative choices (which are, admittedly, much less sexy topics than the emotion and intellectual "value" of the humanities) to divert resources away from those disciplines.

Last week, University of Chicago classics professor Clifford Ando wrote a detailed article on how the money gets spent at his institution, arguing that declines in the humanities are a matter of choice rather than financial necessity. It's a lengthy article, focusing on presidential compensation, the persistent decision by the upper administration to take on financial risk, the expansion of professional (business, etc.) schools, and more. At one point, Ando writes:

The Humanities Division at the University of Chicago spends just shy of 95 percent of its budget on salary and benefits. It is impossible to cut the budget, again and again, without cutting people—but since its budget, in a world of revenue-centered management, depends crucially on aggregate undergraduate enrollment, cutting people strikes at its ability to sustain and, indeed, justify itself down the line. So the Division has been doing more and more of its teaching not by means of “expensive” research faculty, but rather via instructional staff whose cost per course is much less and who are not required to perform research. The human costs and the challenges to the community of such moves are well known to everyone in the University; the costs are also epistemic, because the total coverage of areas of inquiry by research faculty is notably reduced.

In other words, Ando is describing a recursive doom loop: a smaller budget means fewer instructors and available seats for students which means fewer students which means smaller budgets. The only way to plug the gap is through cheap part-time instructors.

They key here is this concept of "responsibility centered management" (RCM - also known as "Incentive-Based Budgeting" or IBB), where units are charged with bringing in their own money to operate (UChicago moved to a slightly modified version of this budget model in 2018). But this budget model didn't just happen - it's not even really that old! - and it's not the only way of doing things. There's a history here.

Kevin McClure has written a bit about the widespread adoption of RCM for the AAUP. The idea originates, as many bad things do, with an idea out of Harvard. Supposedly, since the 19th century, their budget principle has been "Every Tub on its Own Bottom." As explained by Harvard Magazine, "In Harvard parlance, a tub is a high-level institutional unit... Each tub is expected to be self-financing: to prepare its own budgets, raise its own funds, and keep itself solvent." This idea was then spread to UPenn in the mid 1970s by Jon Strauss, an electrical engineer who was hired as a Professor of Computer Sciences at UPenn and then suddenly promoted (for... reasons?) to the VP Budget and Finance. Strauss was then hired away to the University of Southern California in 1981, brought this new budget model with him, and teamed up with John R Curry to spread the good word.

From there, like missionaries, they helped colonize universities across the country - between them working at UCLA, CalTech, MIT, WPI, Harvey Mudd, and Texas Tech, and then countless others through their work in consulting.

The problems with RCM/ IBB are many but we'll focus on 2. First, briefly, as McClure emphasizes in his AAUP piece, there's been almost no empirical study of whether or not this budget model actually works. One of the few that has been done - from 2006 - showed VERY mixed results, even just in regards to economic "efficiency."

The second issue, but the more important one that relates to Ando's piece above, is that RCM/ IBB has been a soft coup that steals power at the university away from the faculty.

In a 2002 article by Curry and Strauss, reflecting back on their years spreading RCM to other universities, they write in their opening paragraphs:

Decentralization is a natural act in universities. Decentralization of authority, that is. Decentralization of responsibility is not a natural act. That requires intention and design. Many academic leaders will say that most authority lies with the faculty in departments and schools, and most responsibility lies with central administrators...

Faculty make decisions within departments about curriculum, admissions requirements, class size, and numbers of sections offered. Such decisions affect the number of admissible freshmen, access to popular majors, and time until degree. These, in turn, can have major impacts on enrollments, and hence tuition revenues. Yet such decisions are all too often uninformed by their financial consequences. Revenues are someone else's problem: the provost's, the admissions director's, or the chief financial officer's; that is, the people responsible for revenues.

Look at this again. Pay attention to its framing. Faculty are a burden. The university - meaning its people - are a burden. The faculty, who indeed did and indeed SHOULD make decisions on curriculum, admissions, time to degree (you know, what a university does), are faulted for having that authority, so it's taken from them.

Isn't it the responsibility of the upper administration to manage the running of the university, to ensure that it can carry out its function? What RCM then does, in other words, is to change the function of the university - away from a place of education that serves a public, to one of exploitation. Here, there is no public good.

Just to point out one very basic fact - with RCM, even if you believe its stated goals, upper administration has no ways of generating their own revenue. There always has to be something outside the system and it has to pull from somewhere. Where it pulls from is, then, a choice. And that choice has, persistently, been to suck the blood from the core of the university from its medieval origins to today: the Humanities.

Add a comment: