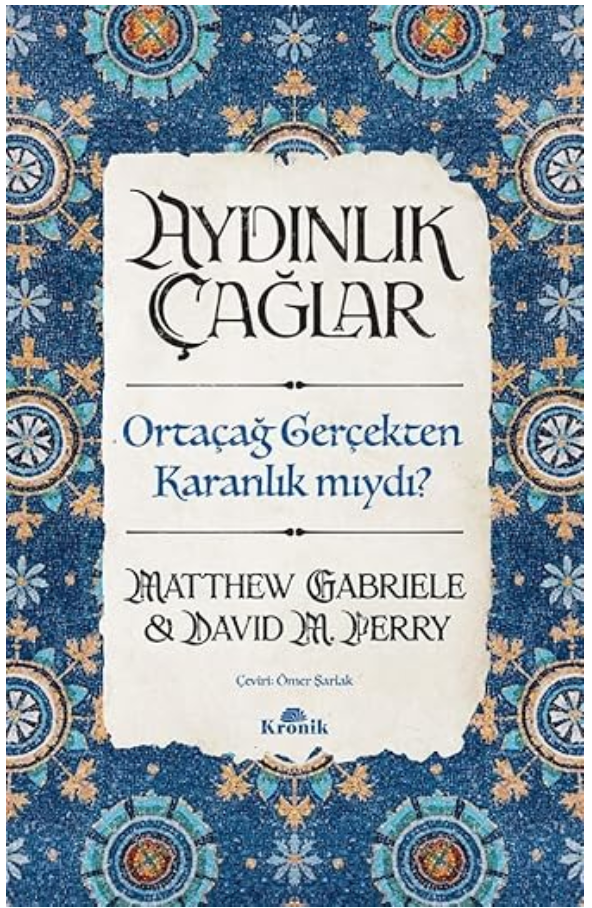

The Bright Ages in Turkey

A peek into the process of translation, thanks to Ömer Şarlak

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

The Bright Ages has now been translated into many languages, but it’s mostly a mysterious process. Our agents contact us with an offer, we agree, we each get a tiny check, years go by, and then one day a translated edition shows up on our doorstep. It’s magical and mysterious to see “your book” but in different alphabets, sometimes with wholly reimagined artwork, and to wonder what the text actually says. This is especially interesting because some wordplay lies at the very heart of the book, our shift from “dark ages” to “bright.” Does that metaphorical shift work in other languages? We mostly don’t know.

Except in Turkish, where the translator, Ömer Şarlak, reached out on Bluesky to tell us about the translation and chat with us about his process. He also offered to translate, and share, his preface to the Turkish edition, which we’ve published in full below.

Translator’s Preface

Before getting started, I must address certain conceptual issues that, while some have been resolved in the original language of the book and others remain subjects of ongoing debate, are particularly significant when translating into Turkish. I wish to make it absolutely clear that I have no intention of "stealing the authors’ role." As such, rather than drafting extensive treatises on these matters, I would like to briefly share with readers the nuanced challenges I encountered during the translation process.

The first and perhaps most critical issue is avoiding the conflation of ortaçağ (lowercase, one word) as a cultural concept with Orta Çağ (uppercase, separated) as a historical time period. While we lack definitive evidence regarding whether the notion of dividing time into distinct periods was used with such clarity in earlier times, Augustine, in his Confessions, divides the narrative of his life into six periods: infancy (infantia), childhood (pueritia), adolescence (adolescentia), youth (iuventus), maturity (gravitas), and old age (senectus). Similarly, in the ninth book of The City of God, Augustine identifies six epochs: "the first from Adam to Noah, the second from Noah to Abraham, the third from Abraham to David, the fourth from David to the Babylonian captivity, the fifth from the Babylonian captivity to the birth of Christ, and the sixth lasting until the end of time." The first narrative is structured like the second.

Turning to a thinker from more recent times, Voltaire divides time into four periods. In his 1751 work Le Siècle de Louis XIV, the term siècle (century) does not refer to the span of one hundred years beginning with “00” and ending with “99,” as it might commonly suggest, but rather to an “era,” similar to the modern Turkish usage of the term çağ. However, Voltaire refrains from assigning specific names to these eras.

The first instance of naming historical periods occurs earlier, in the 14th century. Petrarch (1304–1374) referred to the period between Rome and his own time as media ætas, meaning the "Middle Ages." For Petrarch, the Roman period represented the old (ancien), while the humanist thought of his own time, which he identified with, represented the new (moderne). According to Jacques Le Goff, the term "Middle Ages" was first employed as a chronological designation by Giovanni Andrea Bussi (1417–1475), the papal librarian, in 1469. However, neither the Middle Ages ended there, nor did debates surrounding the term.

As you can see, both the division of history into distinct periods and the naming of these periods have a complex and long-standing history. In Turkish, the term ortaçağ encompasses two distinct concepts. One refers to the span of time denoted in the original text as the Middle Ages. Following the perspectives of Voltaire and Le Goff, I deemed it appropriate to translate this as Orta Asırlar ("Middle Ages"). The other meaning of ortaçağ in Turkish includes the cultural aspects of the time, such as its prevailing thought, architecture, politics, and sociological structures. This corresponds to the term medieval in the original text. Throughout this work, instances of ortaçağ should be understood in this latter sense.

Another issue I have addressed throughout the book concerns the names of the characters. Predictably, the authors have opted to use names that are well-known and familiar within the English-speaking world. However, with all due respect, I have chosen to use either the well-established Turkish equivalents—for instance, Şarlman (Charlemagne)—or the original names in their historical periods and languages, particularly as we journey across three continents and through various nations, beliefs, and cultures in the course of the book. For instance, historical figures universally referred to as "William" in the text are rendered as Guillaume, Duke of Normandy; Wilhelmus, son of Charles the Bald; Kaiser Wilhelm II; or Willem of Rubruck, depending on the context. Although it does not appear in the book, the name "William" also has variations such as Guillerme in Spanish, Guglielmo in Italian, and Guillem in Catalan. In preserving this diversity, I drew upon the privilege of being part of a Mediterranean civilisation that, at the crossroads of Asia and Europe, bears traces of numerous cultures from both continents. I hope readers and the authors alike will understand these nuanced choices.

The meticulous work of our esteemed authors, Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry, is both awe-inspiring in its historical depth and perspective and captivating in its literary richness. I must confess that preserving this richness in Turkish proved to be a challenging endeavour. To maintain this depth, I employed certain terms and concepts that may not seem immediately familiar in everyday usage. For this reason, I hope readers will find the glossary I included at the end of the text useful.

Lastly, I must express my heartfelt gratitude to my mother, who patiently understood when I had to place some household responsibilities on the back burner during the months I dedicated to this translation. I am deeply indebted to my long-time friend —"şekerim"—Ertuğrul İnanç who shared my enthusiasm from the very beginning, illuminated my path with his profound knowledge of the Middle Ages and antiquity, offered valuable feedback during our joint readings, corrected my mistakes, endured my moods, and patiently assisted me with the concepts and sentences I, perhaps excessively, dwelled upon. Lastly, I am grateful to Nurgül Koç, who persistently encouraged me to keep my language simple and fluent whenever I risked making the text overly complex.

Our great thanks to Ömer Şarlak.

-

Such a fascinating read!

-

-

It seems you are fortunate to have Ömer as your translator!

-

wow, what a blessing to have someone as passionate about their own culture and your book to make such effort to get it right, so that the people reading in that language will best understand what you were trying to convey. Congratulations on creating a book that inspired such a person to do his best.

-

Thank you for sharing this look into the “back of the house”!

-

Translation IS a tedious business … and I agree completly with you. Really good translators are hard to find and the above is really rare. A huge eloge to Mr Ömer Sarlak 👌🏻 (and his mother)

Add a comment: