Human Monsters and Monstrous Humans

An interview with Dr. Surekha Davies about her new book

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

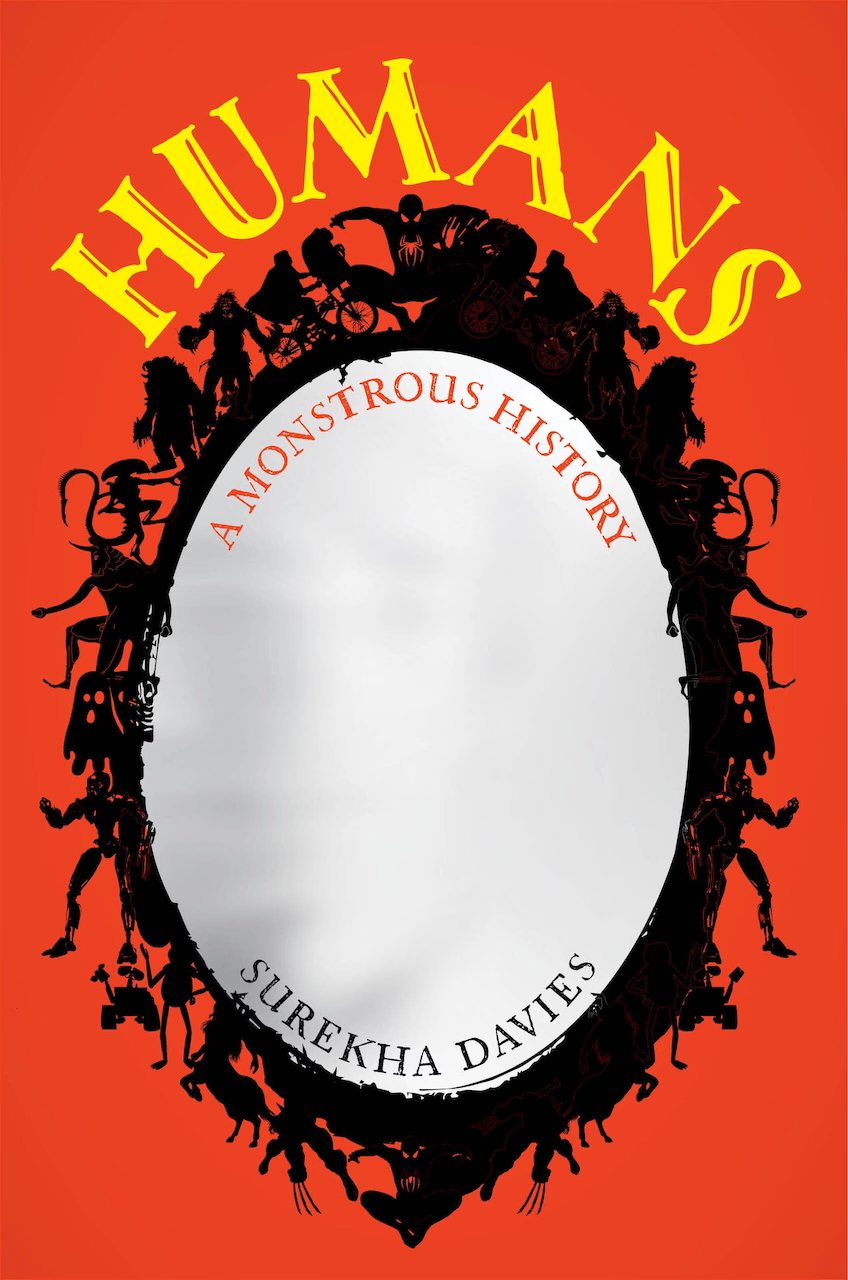

We’re delighted to have recently received a copy of a great new book - Humans: A Monstrous History, just out recently from University of California Press, written by Dr. Surekha Davies. The book, overall, is a history of how we classify things we think we don’t know. We create monsters outside ourselves, sometimes with horrible consequences.

We were lucky to meet Dr. Davies earlier this year and contacted her over email. Her responses to our questions are below (it has been very lightly edited for clarity):

How did you become interested in writing this book?

There’s a three-part answer. First, I watched too much Star Trek as a child.1 Between that and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, encountering extraterrestrials was at the top of my bucket-list. When I studied history of science at college, it was inevitable that I’d do my BA dissertation on sixteenth-century encounters between Europeans and Indigenous peoples in the Americas. I discovered that I could experience the “encountering Martians” feeling by studying first-contact moments between the so-called Old World and the New.

Second, I noticed that European maps of this period often contained distinctive images and descriptions of peoples of the Americas: Brazilian “cannibals,” Patagonian “giants,” the supposedly headless Ewaipanoma and Amazons of Guiana, the city-dwellers of the Mexica and Inca empires, and so on. A number of these maps explicitly described some of these peoples as monstrous. These maps then became the subject of my PhD dissertation and eventually my first book, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters. By this point I’d noticed that “monster” in the most general sense simply meant category-breaker: something that shows where our existing, finite number of categories doesn’t encompass everything in the world. It seemed that a culture’s monsters revealed not monsters per se, but something about how they defined and organized beings in the world.

Finally, in 2014, I was turning that PhD dissertation into a book while on fellowship at the Library of Congress when something happened that flipped a switch in my mind: something that showed me that historians and history nerds weren’t the only people for whom my insights on the age of exploration and on monster-making were relevant. I attended a conference in the building on astrobiology (the study of the origins and early evolution of life on earth and the possibility of life on other planets and in other galaxies). One of the sessions was about how humanity could prepare for apocalyptic alien encounters: intelligent aliens who were hostile, or space microbes that made us sick. All the scientists could talk about was the science side of things – especially weapons. This struck me as mildly ludicrous: as if working on our weapons was likely to lead to a magic bullet sophisticated enough to overpower an alien species that had the technology to get to earth. It was obvious to me that tech wouldn’t save us – that it wasn’t the most important thing to work on.

I hope readers find that the book helps them avoid falling for today’s monstrifying narratives… Today’s tech and especially AI company CEOs are using a playbook of dehumanization, but with a difference: almost no one will be left who counts as a person whose rights will not be trampled, whose data and creative works will not claimed by corporations. And if we outsource creative activities that are the essence of being human – like writing, painting, making music, and performing, actions with which we share our brains and souls with others, activities that transform us through the effort they require – will we still be human? By defining what tech is for, we’re re-defining what humans supposedly are.

So in the q and a period, up went my hand.

I asked: shouldn’t “preparing for discovery” include preparing society for dealing with the fact that intelligent life had been found, or that aliens or space germs were on earth? How would people deal with an event that seemed to go against their religion? What if there was widespread panic and looting? And if humanity is to find solutions, either to communication impasses with aliens or to a space-based pandemic, shouldn’t we learn how to get on with one another better, first?

As I laid out my questions, people in the audience nodded – but the chair of the session looked cross, and he cut me off, saying “that’s the wrong question.” Evidently all he wanted to talk about was scientific and military solutions. This is when I realized just how much I, as a historian of sixteenth-century cultural encounters, had to offer to science and public policy, insights that at least some people in those fields had no clue about. And I began to realize that that “something” had to do with understanding how and why people categorize and classify beings in the world the way they do, and the consequences this has for how people interact with said beings (humans and everything else). It seemed important to find a way to share my expertise with a broader audience than academics and students in the humanities, at some point.

This is, of course, a deeply learned book that draws from your academic expertise. But the book is so readable and clearly aimed at a wider audience. How and why did you decide to make that transition in scope/ tone?

Well, when I started I thought I might be leaving academia soon. My first book had come out at the end of my fourth year in a teaching-focused job, and had won prizes. Yet research-focused universities wouldn’t hire me and my own institution was in financial trouble. There were hardly any jobs in my fields, especially if you weren’t prepared to move anywhere, anytime, for short-term contracts, for work that didn’t leave much time for research and writing on topics of your own choosing. I’d already crossed the Atlantic twice for academic jobs and was now in a fixed-term appointment. I’d been applying for jobs in half a dozen countries (a full-time job for someone who works across disciplines and continents). I had spent a decade writing job and and grant application materials instead of writing books – that’s a LOT of writing time. I was done waiting around for academia. Perhaps, I thought, I could make a living making very different things with words.

Second, not enough of the findings of academic research make it into the public sphere in genres and writing styles that reach a general audience. There was, for me, an ethical imperative to becoming a public intellectual.

Third, the lens of monsters had, as I saw it, immense potential for telling big, sweeping histories. I could imagine writing something that was fun and exciting for general readers, and that also gave them a fresh way to understand the categories that lie behind politics, economics, science, race, gender, culture, and technology. I wanted to write a big book about big ideas that would add “monster history” as a serious, significant theme and form of analysis. And I wanted the form of the book to emerge out of the sources and the questions, rather than mimicking “big history” books on conventional topics.

Having decided that I was going to write this book for a general audience, I looked at a bunch of other trade history books to get a sense of the range of possibilities for scope, structure, and style. I also looked at popular science books: I’d say that my book contains elements of popular science writing as well as popular history writing (in which there are a lot of different styles). And I began to read a lot more fiction and literary/culture magazines, like the New Yorker. Longform documentary journalism turned out to be a great model in the early stages of writing. For the next book, I’d like to also learn from the models that fiction has to offer for immersive storytelling.

Did anything surprise you in doing the research or writing?

I was surprised to find how intellectually demanding it was to write this book, even though I had regularly taught a history of monsters class and had written a book about Renaissance European monster-making. The writing process was challenging in a good way: stretching my problem-solving muscles, activating zany creativity, making me think about structure, voice, and pacing. Writing and revising this book was WAY more intellectually challenging and rewarding that writing my academic monograph (which was itself wide-ranging and ambitious). For future books, I’ll want to map out the scope in ways that leave me more time to create immersive stories as opposed to reading and digesting mountains of material. Distilling important ideas and information into writing that’s at once readable, exciting, and beautiful takes time. At stake is the number of people who will read, absorb, and talk about the ideas, and be changed by them.

Your Epilogue ends with something like a “call to action.” What do you hope emerges from the book, from those who engage with it?

I hope readers find that the book helps them avoid falling for today’s monstrifying narratives.

The first lesson is to recognize monstrification for what it is: a storytelling process that pushes people out of the category of the normal, even of the human. Monstrifying turns off the empathy button. Perhaps readers will remember how in the 19th century, for example, individuals who were differently abled or embodied, or who were kidnapped overseas or coerced to board ships sailing to Europe or North America, were treated by scientists, impresarios, and the general public as objects of entertainment, not as thinking, feeling, people — people who deserved privacy, dignity, and agency over their own lives. We should beware losing empathy towards people who are different. There are other ways to respond to the fact that, in the end, each of us is unique.

Part of recognizing monstrifying narratives involves noticing the hidden agendas of people pushing these narratives. Stories about how people who look different from the average person in a community, or whose religion is different from that of the local majority or of whoever’s in power, often tap into older patterns of dehumanization. Sexist, gender-normative, classist, racist, and antisemitic stereotypes in the present draw on longstanding myths about how entire classes of people deserve “less” because they are lesser beings. At times, stories about them hinge on how they are supposedly a threat to “normal” people.

And third, I hope readers better appreciate how monster-making is contagious: claiming that some of us are a threat to the body politic on the basis of our gender, embodiment, private lives, place of birth, or nationality is only a step or two away from declaring that everyone is a threat. This is a message to talk about with your friends, relatives, colleagues, and bookclubs!

Today’s tech and especially AI company CEOs are using a playbook of dehumanization, but with a difference: almost no one will be left who counts as a person whose rights will not be trampled, whose data and creative works will not claimed by corporations. And if we outsource creative activities that are the essence of being human – like writing, painting, making music, and performing, actions with which we share our brains and souls with others, activities that transform us through the effort they require – will we still be human? By defining what tech is for, we’re re-defining what humans supposedly are.

Anything else we should know?

I write a free newsletter, Notes from an Everything Historian: https://buttondown.com/surekhadavies.2 It’s about history, science, culture, books, monsters, writing, and life as a full-time authorpreneur. Also, I’m currently on book tour in the US, and will be in the UK in late April. A few of these talks will be online/hybrid; a few are being recorded and will be streamable afterwards. And I’ve recorded bunch of podcast episodes! For all this and more, my website, surekhadavies.org, is the info hub, and signing up for my newsletter is a way to receive updates on future events and recordings. And I’m on BlueSky at @drsurekhadavies.bsky.social.

Add a comment: