Medieval Women: In their own words

A guest post about the stunning new exhibition on "Medieval Women" now on at the British Library

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

(from Matt and David: This is a guest post by Phoebe Joyce from @thehistorybelles. Go follow them - immediately! - on Instagram.)

On 21st March 1478 Constance Reynyforth made plans for a servant to collect a forged letter. That letter, supposedly from her uncle, would allow Constance to secretly meet with her lover, John Paston II. Later, Paston’s wife Margaret will provide 10 marks to his and Constance’s illegitimate daughter after Constance’s death in 1484. Not two years later, Alice Claver (successfully) petitioned King Edward IV for economic protections; as a skilled silk woman in medieval England, records show the king regularly commissioning and paying for her goods. It’s no wonder the king granted her requests.

Constance, Alice, and Margaret are just a few touchpoints in the British Library’s astonishing new exhibition Medieval Women: In Their Own Words which runs until 2nd March 2025. Quite frankly, the exhibition (and accompanying events programme both in person and online) is so good that at the time of writing I’ve visited twice. It’s rich in detail and brings the visitor face to face with women we who study the medieval world know well (I’m looking at you, Hildegard of Bingen and Margery Kempe) as well as those that we don’t. Women we think we know but whose footprints in the archive has been accessible only to academics or those with the knowhow to navigate and immerse themselves in these sources.

The focus of the exhibition overall is on the ‘real’ lives of women across the social and economic divides of their periods. In that focus, real moments of humanity come through. Lead Curator Dr Eleanor Jackson is quoted in The Guardian as wanting to ‘show a real richness of women’s lives and culture from the period’ and the exhibition certainly does that. The idea of agency in medieval women’s lives is explored in such a nuanced way that the medieval world comes alive. Alice Crane writes to her dear friend Margaret Paston in c.1455 enquiring about her friend’s health after a bout of illness. Alice poignantly thanks Margaret for her friendship before signing off in her own hand. Across the channel, Joan of Arc dictates a letter requesting supplies for her planned siege of La-Charité-sur-Loire, but signs her own name at the bottom in a shaky, rudimentary hand, identifying her as one not used to making her own mark on the page. Whilst the gulf between them is wide, the parallel between Alice and Joan – asserting that they themselves had a voice in this world - is moving.

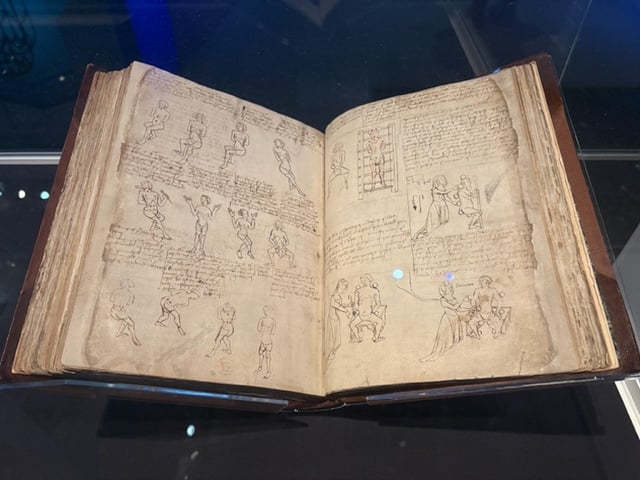

When reinstating women into their place in history, oftentimes the best of intentions can censor the lived experience of the past; it can be tempting to write women back into history as reflecting values we pin so much on today. But the research and curation of Medieval Women doesn’t fall into this trap. There’s no attempt to make women of the past modern, feminist, or independent in a way that isn’t accurate to their circumstances. A delicious medieval treatise from the 15th century provides detailed imagery of women administering cupping treatment exclusively to men, a technique which is still used today. In another instance, Margaret Starre, whilst scattering the burnt ashes of Cambridge University documents during the Peasant’s Revolt, reportedly shouts ‘Away with the learning of clerks! Away with it!’ .It’s clear that female agency comes in all different shapes, sizes… and cups.

There are, of course, women who broke the mould and defied expectations. Maria Moriana, who was likely an enslaved woman of colour, petitions the Mayor and Sheriff of London in the late 15th century after refusing to be sold by her captor. The Bolognian noblewoman Nicolosa Sanuti argues against sumptuary laws restricting the clothing of women, because Sanuti believes that women’s overall contribution to society meant they had earned the right to wear whatever they please. In other words, women had agency and hold space in both their seen and unseen contributions to medieval society.

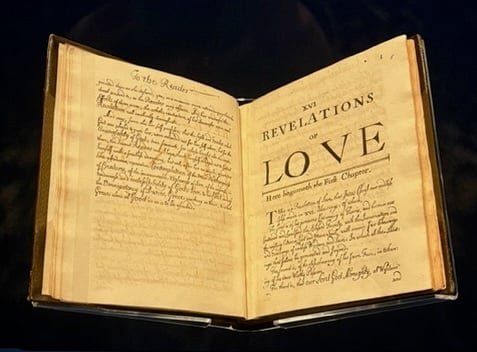

A personal highlight was seeing the surviving copies of Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love for the first time. A heroine of mine, Julian’s withdrawal from society and borderline heretical writings on God’s motherly love all from within her anchoress’s cell, gives a snapshot into how varied women’s lives as well as their own personal rebellions could be. For Julian, her act of rebellion came from withdrawing from the world, whereas someone like Marguerite Porete’s assertion of her agency came in throwing herself into preachings, public speaking and ultimately the stake.

In many ways, the exhibition’s ‘wow moments’ are in the mundane and the moments that show us that at the crux of it all were women’s relationships and an innate desire to muddle through life with whatever joy they could grasp. For 13th century anchoresses (and myself, a woman married to a man and not God) the joy that comes with ‘ne schule ye habben nan beast bute cat ane’ (‘you should not keep any animals, except a single cat’) is unmatched. But if a cat wasn’t good enough, Annes Wales’ petition to Huw Cae Lloyd for a pet monkey for her nunnery might be more your thing. Criticism from a 12th century treatise on hair and beauty that the issue with young girls of marriageable age is that they spend too much time in front of a mirror and applying make up to ensure good matches for themselves, is deserving of a chuckle from the medieval and modern woman alike.

Whilst the plethora of manuscripts and written work on display will occupy you for hours, fans of material culture and the tangible connection to the past it brings will not be disappointed. Early in the exhibition we encounter immersive audio recordings taken from a medical treatise giving advice on women’s health. These add a poignant reminder that the ideas in these texts were being shared used – shared orally by and for the benefit of women who lived in the world. The exhibition also encourages you to smell hair perfume and breath freshener recipes recommended in the 12th century work De ornatu mulierum. As the path of the exhibition takes us towards female mystics, visionaries and nuns, Julian of Norwich’s description of the stench that accompanies her vision of the devil has been carefully recreated and certainly wakes you up! Alongside, Margery Kempe’s olfactory experience of the presence of angels is a sweeter antidote.

Additional highlights include a 15th century English birthing girdle covered in prayers, charms and an apparently to-scale depiction of Christ’s wound. All of which endeavour to keep mother and baby safe during birth. The skull of a lion found at the Tower of London believed to belong to Margaret of Anjou stopped me in my tracks!

I leave you then with one of my favourite items from Medieval Women. Midway through the exhibition we meet Eleanor Rykener, a sex worker born John Rykener. We begin to uncover her story through the documentation of her trial (likely for sodomy) in 1395. Here, Eleanor stated that she undertook a range of jobs to keep food on the table and a roof over her head, including as a barmaid and embroideress. We know so little about her, but the exhibition allows us to imagine; and thanks to this exhibition I can indeed imagine that Eleanor, whilst on the margins of society, had a community of friends around her, people to nod too in the street, people who would comfort her during her trial and who would miss her when she was gone.

Phoebe Joyce holds a BA and MA from Queen Mary, University of London, where she specialised in medieval and early modern British history. Her academic work includes in-depth theses on exorcism in the late 1580s, as well the constriction and self-fashioning of Mary I’s queenship. Phoebe currently works in leadership at HM Tower of London, blending her historical expertise and passion with practical heritage management. In 2022, she co-founded The History Belles with Annabel Johnstone; from heritage site recommendations, book reviews, and video content on history events across London, The History Belles has something for everyone. In 2024, The History Belles launched The History Belles Classroom, a sister account designed to provide educators with resources and inspiration to bring history to life in the classroom. Through its wide-reaching content and learning-driven approach, The History Belles strives to inspire and make history both accessible and exciting for all.

Add a comment: