Coin Flows and the "End" of the Ancient World

Revisiting Modern Assumptions about the Past

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

We’ve been thinking a bit about the supposed “Fall of Rome” lately.

Well, in fairness, we kind of do that all the time. Part of the reason is that’s just us™, part of the reason is that there’s been some more nonsense on line with econobros and military bros who don’t work on the European Middle Ages (or anything adjacent) confidently stating there was a “Dark Ages,” and then more interestingly (but alas related) we saw this post on Bluesky from Dr. Charles West.

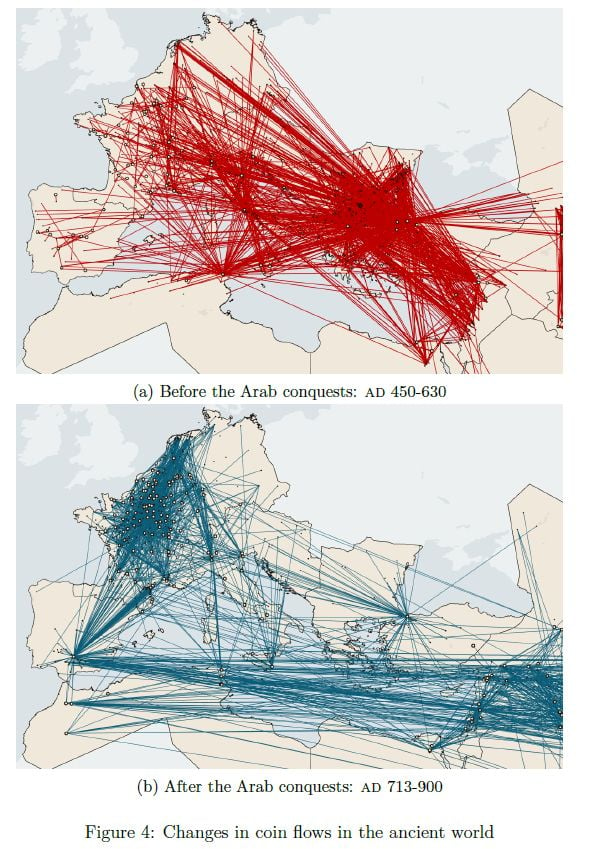

What’s immediately noticeable in the image is how the locus of coinage transmission shifts pretty dramatically between the 7th and 8th centuries. Whereas in the earlier period, everything flows through Constantinople, in the later period coins come from Francia in the West and Baghdad in the East and then flow through Iberia to connect the 2 regions.

Ultimately, this analysis is a revisitation of what’s known as the “Pirenne Thesis” and at its most basic the early 20th-century thesis argued that the rise of Islam functionally ended Antiquity because it severely slowed movement and trade within the Mediterranean. This functionally turned Europe into a backwater, although the thesis concedes that this did allow the rise of the Franks and the creation of their own civilization culminating in Charlemagne.

The (to the best of my understanding, non peer-reviewed working) paper by 2 economists without training in history that the image is taken from argues that Pirenne was both right and wrong (but mostly right). They argue that there was indeed a “newly formed trade barrier between the emerging Arab Caliphate and the Christian West” but that drops in trade “cannot have had any meaningful impact on the Frankish economy because pre-conquest trade shares were low” and that “the Byzantine Empire experienced the largest declines in economic activity in the seventh century, being faced with a triple shock of a lowered access to trade, reductions in relative productivity, and a drop in seigniorage revenues.”

Sigh.

In 2017, the scholar Bonnie Effros wrote a peer-reviewed article entitled “The Enduring Attraction of the Pirenne Thesis.” There, she made a couple of key points: first that there’s been a resurgence of interest in the Pirenne Thesis lately mostly among right-wing nationalists and neoconservatives as a way of demonizing Islam as a fundamentally destructive force, and second that Pirenne’s work (from the 1st ½ of the 20th century) is riddled with colonialist assumptions about Islam and the “East.”

That’s not to say that all new revisitations of the Thesis by non-specialists are right-wing politics (though we should be suspicious, given this context, by non-specialists rampaging into fields outside their own), since medievalists of all specializations have at least had to confront the thesis ever since its publication.

And there is, of course, much to admire about Pirenne’s work within its historiographical niche, as Effros so ably demonstrates, she also notes how archeological discoveries have cast the Thesis into fundamental doubt. Ultimately, “evidence has been building that medievalists would do well to avoid focusing on where the Pirenne Thesis is accurate or inaccurate and to move beyond its scaffolding in favor of new questions and parameters.” The future is, instead, “big, messy, and interdisciplinary.”

we cannot ethically read back our own contemporary measures of political and economic “success” onto the premodern world

What this means in relation to the maps above is that, we think, it’s a mistake to make sweeping conclusions about changes to societies and kingdoms based on… coin flow. What the map above shows is a transformation, but one that should be free of value judgment.

Coins moved differently. Evidence is incomplete. Other objects - and people! - moved in different ways during that same period.

But maybe more importantly, and this is why historians are so important to include in these types of analyses, we cannot ethically read back our own contemporary measures of political and economic “success” onto the premodern world. We measure success by international trade and stable currency - but, although those were certainly important in the period we’re taking about, they’re not the measures they used in the past.

Here we have evidence about coins. Does that reflect something bigger? Well, for that, you gotta do more reading, man.1

Just as reminder, and in a serendipitous coincidence, Matt’s podcast “American Medieval” is now available! Two episodes are out now and a new one is coming this week. Indeed, this week (Wednesday), he’s happy to be hosting the amazing Sarah E. Bond and we’re talking about… Rome and why Americans kind of need the supposed “Fall of Rome” so much.

Please consider subscribing, or just have a listen for free! Subscriptions are 30% off this November, with code “ALLYEAR.” What a deal!!!

Economists. ↩

Add a comment: