Carolingian Biodiversity

How Interdisciplinary Can and Should Work

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

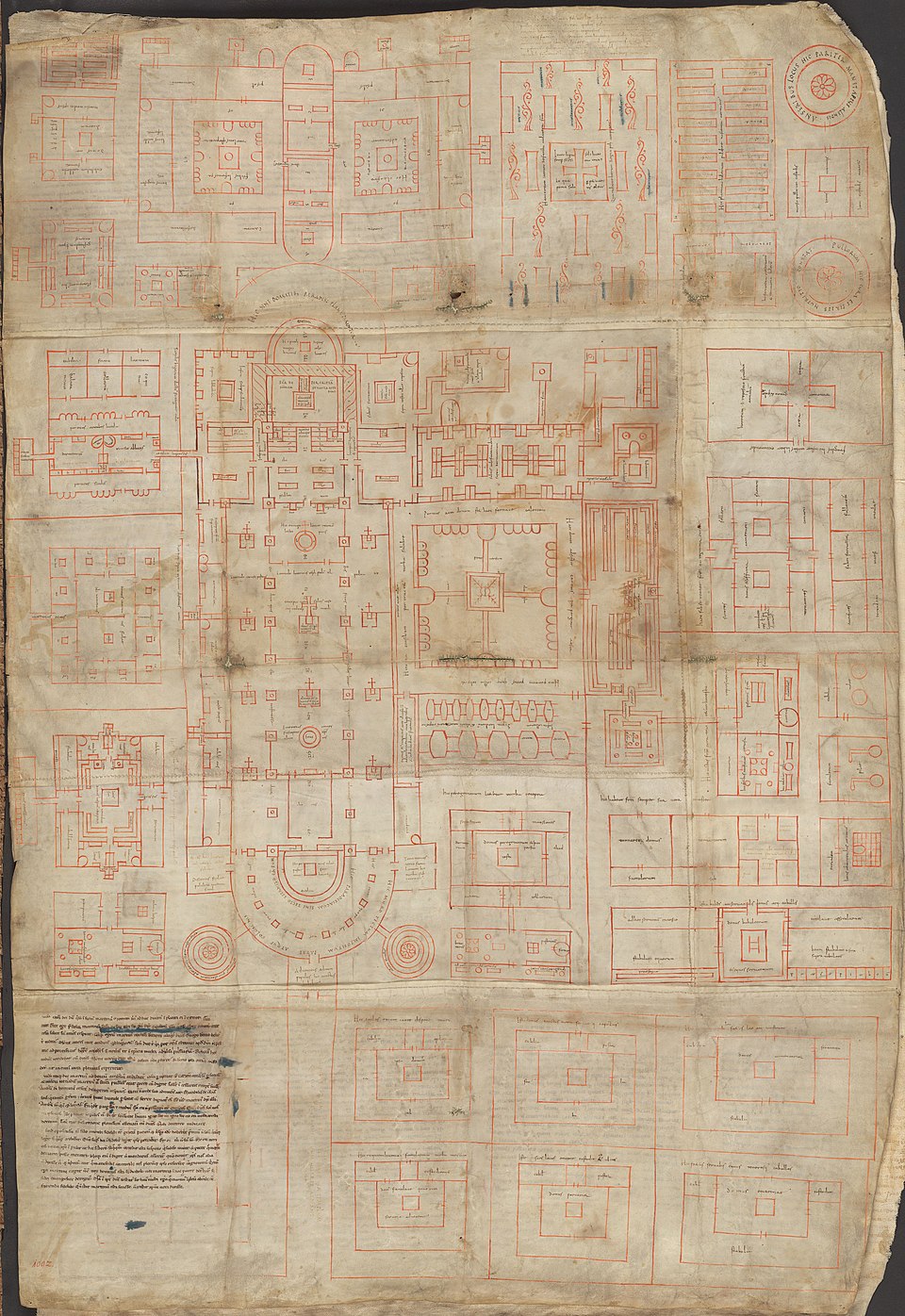

In the 8th century CE, along the shores of Lake Constance in what is today Southwestern Germany, the monks of St. Gall gradually came into possession of more and more agricultural territory thanks to gifts from Carolingian nobles. The lands they oversaw were fertile and rich, and the monks sought to organize to holdings, so did what monks like to do - write things down. The resulting records of the Abbey of St. Gall offer a rare archival portrait of agricultural management in the late 8th century, just as the Carolingian Empire was growing into its fullest form.

Now, an interdisciplinary team out of the Max Planck Institute, has determined that on account of human agricultural activity, plant biodiversity reached its peak level in the region between 500-1000. Their study is not only important in its findings, but also as a model for how teams of experts in science and archival research can partner to genuinely improve our understanding of the past.

The paper, “Cultural innovation can increase and maintain biodiversity: A case study from medieval Europe,” uses 6 pollen cores to estimate changes in plant diversity in the western Lake Constance region (modern day Switzerland) over the past 4,000 years. They found that:

Pollen-estimated plant diversity along the western shores of Lake Constance expanded markedly in the latter half of the first millennium CE. Regional pollen-estimated plant diversity then dropped significantly around 1350 CE... Pollen-estimated plant diversity then increased again after 1450 CE and remained elevated through the 20th Century [but] it never fully returned to its pre-1350 CE levels.

But, then perhaps more importantly, they combine this analysis with archaeobotanical evidence and historical documents from local archives to identify and describe what happened and when. This research then supported the initial analysis, allowing the researchers to conclude that they too could see diversification of agricultural procedures (i.e. crop rotation to avoid exhausting soil) as a result of human decisions.

In other words, medievals (likely connected to the monastery of St. Gall) worked the land and vastly helped to expand the biodiversity of the region. This has implications for today, because

Landscape mosaicking through agriculture has, in the Lake Constance region and elsewhere, exhibited the potential to increase plant diversity while maintaining society-sustaining food production. If undertaken at the appropriate scale and in a manner respectful of critical ecological thresholds, similar landscape management techniques may be useful in modern biodiversity conservation.

People’s attentiveness to living with the land can lead to much more productive and sustainable agriculture. Just another way that 2025 is saying we should be more medieval.

But let us focus on one other thing. As opposed to some other recent research, this study on biodiversity seems like an ideal model for interdisciplinary work — not scientists swooping in to solve history for us humanists, but rather robust partnerships that connect genuinely new evidence from scientific analysis to the expertise of those who have been studying the region for a long time using archival sources.

And as a result, we all genuinely learn more.

Add a comment: