1066 and 1944 ("Medieval" D-Day)

Using the Middle Ages to Remember a Modern War

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

As I’m sure many of you already know, June 6 is the anniversary of D-Day - the day, in 1944, when a massive Allied landing took place in Normandy and began the endgame of World War II. What many don’t know, however, is how the war in Europe shaped how we understand the medieval past.

Robert Bartlett, for example, has a new book coming out on the huge number of archives destroyed (both accidentally and on purpose) in the centuries after the end of the Middle Ages.

But the war machines that moved across Europe in the 1940s destroyed much more. Today, we’re exceptionally happy to welcome a guest post by Prof. Leonie Hicks of Canterbury Christ Church University (UK). Prof. Hicks is an exceptional scholar of medieval Normandy and her piece below meditates on D-Day and how its impacted how we know about medieval Normandy.

Enjoy the guest post, then go buy Prof. Hicks’ book - A Short History of the Normans.

‘We once conquered by William have now set free the Conqueror’s native land’’ reads the inscription in Latin on the memorial at the British Military Cemetery in Bayeux. This resting place of those who died during D-Day and the Battle of Normandy speaks to a link between the events of 6 June 1944 and those of 14 October 1066.

For historians of medieval Normandy, like myself, the two events are connected in all sorts of ways. D-Day and the ensuing battle saw heavy military and civilian casualties and these are rightly remembered. But less well know is the destruction to the material culture of the region. History is also a casualty of war.

For example, the Archives départementales de Manches were destroyed by the Americans during their aerial bombardment of the city on D-Day itself. Not only was the city destroyed but so was the cultural memory of the region through the loss of irreplaceable documents. In addition, some of the famous churches and abbeys built by William the Conqueror, Duchess Matilda and their court also played a role in the events the liberation. William’s magnificent abbey of St Etienne (Abbaye aux Hommes) in Caen served as a shelter for the citizens of the city during the fierce battle for control of the city between June and August 1944. It was thankfully spared bombing as the people hung an enormous red cross flag outside. And interestingly, the abbey’s use as a refuge is a direct echo of medieval church council statutes that enabled the use of sacred spaces as shelter in times of war.

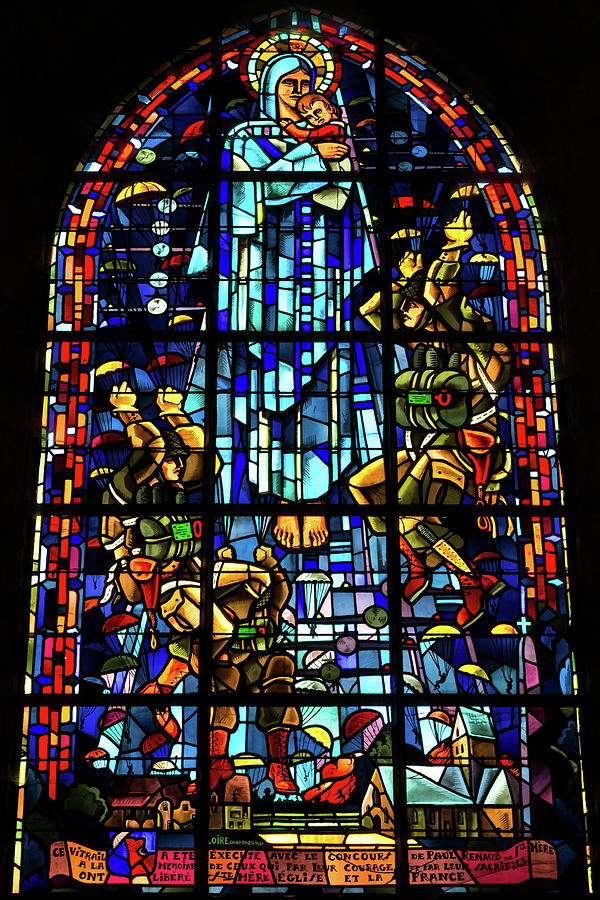

After the war beginning in 1945, Norman history provided inspiration for the commemoration of D-Day and the liberation. In some of the neo-gothic churches of the region, new stained glass commemorated different, modern warriors. In the town of Ouistreham (the port of Caen), British units involved in the capture of Pegasus Bridge are honoured in some of the church windows of the church of St Samson. You can also see a depiction of paratroopers descending from the sky at Sainte-Mère-Église along with St Michael, patron of paratroopers and also one of the Normans’ favoured saints.

That most famous of Norman artefacts, the Bayeux Tapestry, provided plenty of inspiration for journalist, artists and politicians who wanted to mark the D-Day. The 15 June 1944 issue of The New Yorker, the one printed just after the Allied landing, took elements from the embroidery, including a soldier looking out from up a tree, for its cover design. Montgomery and Eisenhower pour over a map. Instead of ships full of horses and knights, we see infantry in landing craft supported by the navy and air force.

Indeed, new “medieval” artifacts were created. Hanging in the D-Day museum in Portsmouth is the Operation Overlord Embroidery designed by Sandra Lawrence and commissioned by Lord Dulverton in 1968 who had visited the Tapestry in Bayeux. This piece pays tribute to the backroom staff, like the map-plotters, but does not shy away from depicting the horror of war, particularly the American landing at Omaha Beach and the battle for Caen. It is a moving testimony to the Allied campaign and includes fabric from military uniforms and regimental patches. Lawrence’s original paintings from which the embroidery was worked are now in The Pentagon.

As preparations are underway to mark another significant anniversary for Normandy and the United Kingdom in a few years’ time, that of the birth of William the Conqueror (b.1027), the echoes of 1066 in 1944 serve asa reminder of a millennium-long shared history.

-

It is fascinating how the propaganda and military commemorations of the Middle Ages were transformed in honor and reverence for the past into something commemorating a modern liberation. The paratrooper frieze is beautiful. I hope to see more articles like this. I originally subscribed to you via substack. I am still writing myself on substack on legal issues. I wanted to pitch co-writing an article with you on trial by combat. Funny enough, the history of this medieval court proceeding is still taught in law schools and I fear it may have more relevance to the present and future than most think. Let me know what you think. Here is a link to my page - https://ryanknutson.substack.com/ .

Best,

Ryan

Add a comment: