Autumn Newsletter: On Habits and History

Hallo From Berlin!

Three weeks ago, my family and I flew to the German capital, where we’ll be living until March while my husband is on sabbatical. He’s working in a lab here, our kids are in a bilingual school, and I’m busy working with my editor on manuscript revisions for my book, which is due out next spring.

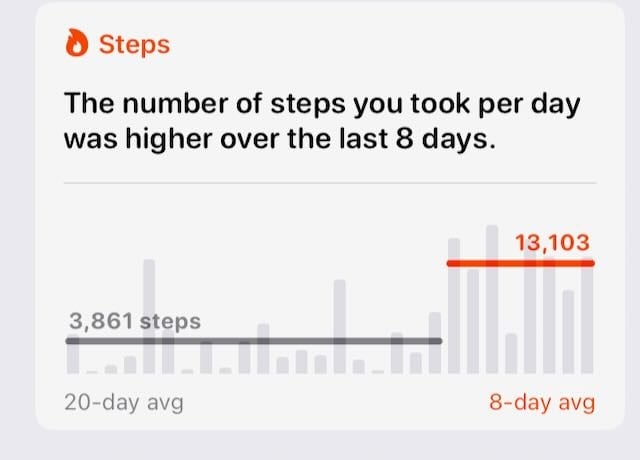

We’ve mostly settled into a routine by now. The kids have joined soccer (ahem-football) teams, we’ve acquired bikes, and we’re enjoying Berlin’s amazing parks and public transit. It’s also a good chance to reflect on the differences between Germany and my home country. Here’s one noticeable difference, brought to you by my cell phone step tracker:

Back in Seattle it’s a struggle for me to be as active as I probably should. I know walking is good for me, and I enjoy it, but I find it difficult to carve out the time. This often feels like a personal failing—the result of my own poor choices. And yeah, okay, it is…to an extent.

But here in Berlin, my step count tripled overnight without me even really giving it much thought. And that has gotten me thinking about the whole ecosystem that surrounds my actions, which can make the good choices either easier or harder— the habitat for my habits, if you will.

Take the habit of walking to the grocery store: good for me, good for the environment, often irritating in practice. But here in Berlin I’ve brought home our groceries almost exclusively on foot, and I honestly kinda like it.

There’s a whole slew of reasons for this:

We have access to a car, but there’s no parking at our apartment, so often as not the car is parked a block or more away: not that convenient. Meanwhile…

there are at least six grocery stores within a three-block radius, ranging from a fancy organic “Biocompany” to the giant Kaufland with its Target vibe.

But the items in all of those stores tend to be smaller; we buy milk by the liter, not the gallon—

—and that’s just as well, because our refrigerator is child-sized. There’s no shelf that would even hold a gallon of milk.

So instead of stocking up for a week, we buy just a few days’ worth of groceries at a time.

Luckily the apartment was furnished with one of those rolling carts, making it easy to carry home a few days’ worth of groceries.

We take the kids to and from school either on foot or on the bus, so twice a day I’m out and about, passing all those stores, and it feels easy to stop and pick up a few things.

I could go on. (All the walking gives me lots of time to think.) But the point is, I have a lot of help here: a lot of things in my environment that support my positive individual choice to walk instead of drive. (This is similar to the tech concept of friction: Berlin has removed a lot of the friction that was holding me back from walking to the store.)

Back in the US, when we talk about big problems—from rising rates of chronic illness to climate change—it feels like the onus is often placed on individuals to solve them. And sure—each one of us must do our part.

But the way to really move the needle on system-wide problems is to shift things within the system itself, so that the easy or default choice for most people becomes the choice that is good for them and good for society.

That’s really what I’m thinking about on all my long walks: how can we, as Peter Maurin of the Catholic Worker Movement suggested, make the kind of society “where it is easier for people to be good”?

Hackeschermarkt train station Recommended Reading

You know the Faulkner quote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past”? Berlin is a great place to be reminded of this. Nearly everywhere I go I find memorials to, even scars left over from, events I learned about in high school history. It begins to sink in just how recent those events were, and how they continue to shape life today.

Metal plates in the ground through the city center mark the former line of the Berlin Wall, which came down only 36 years ago. This past weekend we attended a football game in the massive stadium built under Hitler for the 1936 Olympics. And throughout the city, you can find Stolpersteine: brass plates, embedded underfoot amid the cobblestones, marking the former homes of people deported and murdered under the Nazi regime.

Stolperstein for Rebecka Hirsch: born 1861, deported to Theresienstadt 1942, died 1943. These Stolpersteine are just one of many memorials to victims of Nazi atrocities across Germany; the country has done significant, admirable work to reckon with that shameful history. I’ve heard it suggested that the US might look to Germany’s example in order to more fully reckon with its own shameful history of slavery. A few years back I read an excellent article on this subject by Clint Smith in The Atlantic. In addition to exploring ways in which this comparison between the US and Germany may indeed be instructive, Smith also outlines some complications and caveats that surprised me and gave me lots to think about. I really recommend the whole article. You can find a gift link here.

Book Updates

Over the summer I had a couple of consults with my editor and the publication team: one about my book title, another about the cover. The less said about the first round of cover designs, the better. Now there’s a revised cover that I think will work with a little more tweaking.

Meanwhile, the team vetoed my original title and asked me to suggest four or five alternatives. So I threw out a title that had been my personal favorite all along but that I’d thought was too obscure. They liked it, but paired it with a new subtitle that helps people clue in to what the book is about. I hope to share it soon.

*

What are you thinking about on your walks these days?

Bis später, alligator,

Mary