Is it Finally Time to Start Talking About Peak Oil Again?

Hi there,

This month, I wanted to dive into about a subject I wrote a lot about years ago but has recently faded from the discourse. As always, I'd love to hear your thoughts.

In the early aughts, a series of books from oil industry experts, petroleum engineers, and physicists warned that global oil production had peaked and would soon begin declining — signaling a world-changing inflection point that could cause recessions, an end to globalization, and potentially, to modern civilization as we knew it.

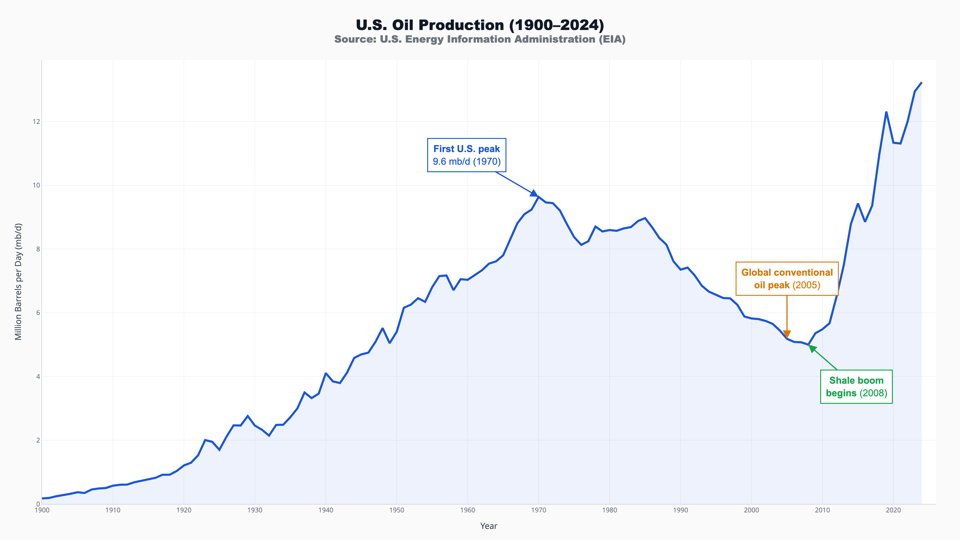

For a brief moment, the peak oil movement seemed prescient. Conventional oil reached a peak in production around 2005-2006. Prices spiked, with Brent crude at one point hitting $145 a barrel in 2008. There was a financial crisis and the global economy collapsed.

But with rising prices, more expensive and difficult ways of producing oil and natural gas became economical. Fracking of shale deposits opened up huge new reserves in shale deposits across the United States. The rapid rise of shale oil in the 2010s turned the United States into a net oil exporter for the first time in many decades.

Fracking also made natural gas so cheap and abundant that companies started liquifying and exporting it overseas. Talk of global oil peak faded.

Now though, it seems possible that the shale boom is stalling out, if not over. As many others have pointed out, U.S. oil production in 2026 is set to decline for the first time in five years.

Last month, Harold Hamm, a famous wildcatter, told Bloomberg that he was ending drilling operations in North Dakota for "the first time in over 30 years" — just the latest signal that all might not be well.

Compared to conventional oil, shale oil wells tend to peak and decline rapidly, forcing drillers to keep up with an ever-accelerating treadmill of discovery, drilling, and depletion. Over the past year, there have been a number of industry announcements suggesting that shale production may be hitting limits, at least at current price points. Last June, a top executive from EOG resources (one of the largest oil and gas production companies in the U.S.) said that U.S. shale production is likely in decline.

The problem, according EOG COO Jeff Leitzell, could theoretically be solved with more drilling, but that would degrade the "capital efficiency" investors are demanding today.

What does that mean? In early 2022, Ben Cahill of CSIS gave a concise summaries of the conundrum:

The first decade of the shale boom created jobs, delivered tax revenue to states and the federal government, and helped reduce the trade deficit—but destroyed investor capital on an unprecedented scale. Quarter after quarter, many shale companies reinvested all their cash flow as management teams were incentivized to seek growth rather than returns. The result was a lost decade for investors. According to one estimate, free cash flow for the entire U.S. shale sector for 2010–2019 was a stunning -$300 billion.

In 2020 though, the oil price crashed, decimating the industry. Shale companies consolidated.

This contraction, painful as it was, created a more disciplined and resilient industry ... [companies] focused on paying down debt and returning cash to shareholders through increased dividends and share buybacks ... Capital discipline helped the sector to generate enormous cash flow.

The problem, according to Cahill, is that this lower level of investment is unsustainable.

Last year most shale companies reinvested less than 50 percent of their cash flow in new drilling, as the industry downshifted into “maintenance capex” mode. But initial production rates at wells usually drop off quickly, so companies need to drill continuously to sustain output. They can only pull back on investment for so long without sacrificing future production levels and cash generation.

In other words, U.S. shale oil appears to face a structural Catch-22: invest aggressively to keep the treadmill going and never turn a profit, or cut back on capital expenditures, buy back stock and reduce debt—at the cost of future production.

But even this assumes that there is a never-ending supply to be drilled if the capital is there. At some point however, the best resources are already drilled, and the production gets much harder.

Independent journalist Justin Mikulka has been an early and consistent voice on this topic. In 2018, Mikulka wrote that while shale oil production had been impressive, it had never actually turned a profit:

There is no doubt fracking can lead to production of large volumes of light oil, but it comes at the cost of approximately a quarter trillion dollars more than the industry has made since 2007.

By late 2022, Mikulka was warning that

the U.S. fracking boom is ending far earlier than many industry experts and CEOs predicted. After an understandable dip in 2020 due to the pandemic, oil production still has not regained the record levels achieved in 2019, and predictions that the industry would set new records this year have not materialized, despite 2022’s high oil prices.

At the time, Mikulka argued that industry forecasts were wildly overstated. The builders of the Sea Port Oil Terminal (SPOT), for example, predicted that the United States would be exporting 8 million barrels a day by 2025 (of which SPOT would export 2 million).

The math doesn't add up. U.S. crude oil exports averaged just under 3.5 million barrels per day in the first 11 months of 2022. With U.S. shale oil peaking, how are exports expected to more than double? ... [The SPOT export terminal] perhaps made sense in 2019 when Rystad was predicting a big and bright future for U.S. shale. Now it is likely to be a stranded asset.

Early last year, Enterprise Products Partners announced that the SPOT project "lacks sufficient customer interest to move forward with commercialization." By the end of of the year, the U.S. was exporting just around 4.5 million barrels a day total — 3.5 million barrels short of 2022 projections.

A big part of shale's problem is that, relative to conventional oil, it's expensive to produce under any circumstances. Current oil prices don't support new drilling. The industry estimates a breakeven price of around $61 a barrel; with West Texas Intermediate trading at around $64 a barrel, margins that are too small to justify new wells. But the situation may be worse than that. According to a September report from energy data analytics firm Enverus, the marginal cost of fracked oil today is actually closer to $70 a barrel, and is projected rise to $95 a barrel by the mid 2030s as resources get scarcer. Uncertainty around tariffs and their impact on critical drilling inputs like steel is likely making drillers even more skittish.

The EIA predicts that the price of WTI will drop from an average of $65 a barrel in 2025 $52 in 2026 and $50 in 2027. More production from Venezuela — in the unlikely event that that the Trump administration's adventures there are successful — won't help the industry.

Oil Declines in Other Countries

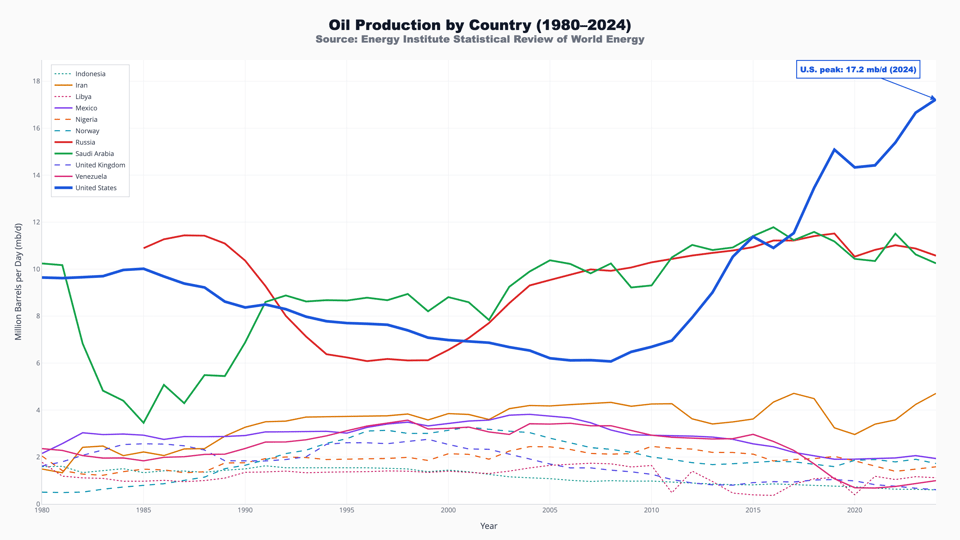

Even as U.S. oil production was rising over the past two decades, it has been falling in many others. As Jeff Kimmel pointed out last week, "Venezuela is not the only country far below its past oil production peak."

The US added 13 million barrels per day over the past 15 years ... 10 countries collectively lost 16 million from their peak levels ... that math (13 million gained, 16 million lost) explains a lot about global energy security and why US production growth has been so geopolitically significant.

Oil's Demand Destruction Problem

In the past, oil production struggles have usually led to price spices and short-to-medium term economic and geopolitical realignments. The first time U.S. oil production peaked, circa 1970, prices spiked, OPEC gained leverage, and the nation entered more than a decade of inflation. In the early 2000s, oil price spikes contributed to the bursting of the housing bubble and the Great Recession — and eventually led to resurgence of production in the United States from shale.

That dynamic has yet to materialize this time around. By all accounts, producers have overshot demand in the last year, leading us into a 2026 global supply glut. Last year China soaked up a lot of the excess supply as it filled its strategic reserves.

There are a number of factors at play, but we shouldn't underestimate the role of structural demand destruction.

In an October 2025 report, the IEA predicted that 1.9 barrels per day of oversupply in 2025 was leading to an "untenable surplus of nearly 4 mb/d in 2026" as OPEC phased out voluntary production cuts.

The report points out that

Oil demand is inelastic by nature, meaning that it takes large oil price moves to materially impact demand in the short term. For example, a lasting 10% rise in oil prices would roughly reduce global oil consumption by around 0.3%.

The flip side is that just because there's oil on the market doesn't mean that people will burn it, especially if they've already made permanent changes to reduce demand.

For example, according to a 2024 IEA report, electric vehicles have already replaced 1.3 million barrels of diesel and gas globally, and that figure could rise to more than 6 million per day by 2030 — even with relatively low prices and a global oil surplus.

Globally, the projected EV fleet displaces 6 million barrels per day (mb/d) of diesel and gasoline in 2030, a sixfold increase on displacement in 2023. By 2035, even less oil is needed for road transport, with displacement reaching 11 mb/d in the STEPS and 12 mb/d in the APS. In fact, we expect global demand for oil-based road transport fuels to peak around 2025.

These are structural changes. In energy markets, "demand destruction" (instead of just demand reduction) typically happens when alternatives become competitive or when efficiency improvements reduce the need for the commodity regardless of its price.

In the years since conventional oil peaked, industry voices have frequently reframed "peak oil" as "peak oil demand" — arguing that the peak and decline of global oil production would be driven not by geologic limits but by the demand side of the market. As an April 2025 blog post from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York explained:

“Peak oil”—the notion that the depletion of accessible petroleum deposits would soon lead to declining global oil output and an upward trend in prices—was widely debated in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Proponents of the peak supply thesis turned out to be wrong, given the introduction of fracking and other new extraction methods. Now the notion of peak oil is back, but in reverse form, with global demand set to flatten and then fade amid growing use of EVs and other low-carbon technologies. The arrival of “peak demand” would turn global oil markets into a zero-sum game: Supply growth in one region or field would simply push down prices, driving out higher-cost producers elsewhere. A key question is how U.S. producers would adapt to the new market environment.

But the idea of peak oil was never that oil would literally vanish, but that extracting what remained would become prohibitively expensive. Peak supply was always really about peak affordable supply; at some price point, demand destroys itself because alternatives become cheaper.

To put it another way, if oil stayed at $20/barrel indefinitely, EV adoption would slow considerably. The "structural change" narrative assumes oil can't sustainably price itself below competing technologies, which is a supply constraint in practice.

So what lies ahead? In the short term, there's a good chance that OPEC+ will cut production to keep prices from collapsing entirely. But these producers also have an incentive to keep prices low enough to keep U.S. producers sidelined as they attempt to retain and grow market share.

Longer term, it's hard to imagine U.S. shale production growing much at all — much less at the rate it did in the early 2010s — especially if the rapid electrification of transportation continues to suck up demand growth and keeps margins too low for shale producers to make a profit.

As for oil peak's implications for the broader energy transition, a lot depends on the trajectory of renewables and other fossil fuels—especially the closely-related fate of natural gas, the subject of my next post.

Until next time,