The Adventures of Ruby

Let’s start of with deep thanks to Discord user trackerbell_4114 for the grounded analysis of the situation.

Who is Ruby?

Ruby (IMO: 9626390, callsign: 9HA3017) is a breakbulk cargo ship currently sailing under the Maltese flag 🇲🇹. She (why do ships always use feminine pronouns?) was in the news because she carried a cargo of “seven times the amount of ammonium nitrate that caused the Beirut explosion” (more info on that incident here).

Why it matters

As you’ll see in the timeline below, ports kept refusing entry to Ruby which must have been endlessly frustrating to the crew. Delaying the responsible offloading of this cargo gives mental strain on the crew and increases the likelihood of an explosion at sea. That would be both tragic for the crew and their kin, and a massive environmental disaster. Trackerbell_4114 provides good explanations on why these refusals happened. But reporting on this vessel has been deeply sensationalist, as trackerbell_4114 says “Dangerous cargo like this passes through waterways near land many times each day.“ It’s not a Russian op or anything like that. The dangers of this ship has been magnified by the media’s thirst for “shock value” in journalism.

Additionally, their reception in Norwegian waters was colored with racism. Local reporting from the Barent Observer said this was a “dangerous vessel” that is staffed with “mostly Syrians”.

Crewing a ship is a dangerous job. Aside from all manner of natural disasters one can expect at sea, people have been trapped and starved on vessels by their employers. So naturally, the people who crew ships are often (but not always) those who are desperate enough to need the work.

Timeline

2024-08-22

According to Newsweek Ruby picked up the cargo from Kandalaksha and was headed to the Las Palmas in the Atlantic.

2024-08-26

Ruby requests refuge from a storm according to Barent Observer.

2024-09-03

According to Newsweek docked at Tromsø.

2024-09-04

Barent Observer report is published, revealing that there is damage to the hull, rudder and propeller. Local fire department assures public that the cargo poses no danger.

2024-09-23

Malta Today reports that entry has been denied. Report also confirms refusal of entry from Lithuania.

2024-09-26

TrackerBell reports that the Ruby is at anchor. There's also a tug (Kamarina, IMO 9499644) that left the Dutch port of Delfshaven last night and seems to be slowly heading for the Ruby. At 2,11 NM (nautical miles) from Ruby, there's also a bunkering vessel (Fortuna III, IMO 9896828) that left Rotterdam last night heading straight for the Ruby. BBC reported on her as she enters UK waters. They confirm that they are about to begin bunkering operations and that damage was due to running aground.

2024-09-28

Trackerbell reports that bunkering started “a few mins ago” (at 15:13 UTC+1). They say that weather is perfect for it at the moment and that they should be done by tomorrow morning.

In-depth analysis of the situation was provided, see below.

2024-09-30

Kamarina is still at anchor but now showing ETA 17 Oct 24 on one site and 11 Oct 24 on all others and changed its destination to Malta OPL (Off Port Limits) with ETA 10 Oct 24 07:00 UTC. Amber II (an anchor hoy IMO: 9425423, callsign: 9HLD9) is still moored in Rotterdam. As for the weather, the forecast for the voyage looks perfect for the next few days.

Fortuna III, has started heading back to Rotterdam, but suddenly stopped after only a short distance. For a short moment, her status indicated that she was heading back to port. Then suddenly a highly unusual status appeared 'Channel 16 for info'. Channel 16 is the emergency radio channel. The status disappeared as quickly as it was given. Since vessels in the vicinity - in their efforts for collision avoidance - continually check the status of all crossing or oncoming vessels, this could mean that the Fortuna III wanted to be of assistance, sort of like a flag pole indicating if you want to know what's happening, listen in on channel 16. Ships don't radio each other directly unless absolutely necessary. Since the Ruby is basically just in the middle of the entrance into the Thames estuary, it could be that ships entering the area - which then come pretty close to the Ruby - keep inquiring about her status for safety reasons.

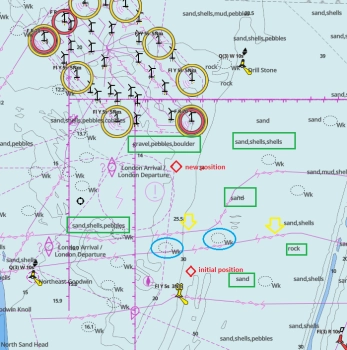

Ruby has shifted locations. She now lies much farther north and west of her original anchoring site. Since her status 'at anchor' never changed, I am assuming that she is dragging her anchor. The problem is that, she's come very close to a 'no go' zone, namely an offshore wind part to her north and west. If the anchor cannot be lifted in time, she would likely drift into the windpark. Since I (trackerbell_4114) measured the distance a few minutes ago, the Ruby has moved North by 0.3 NM.

2024-10-01

New auxiliary vessel appeared - the Carlo Martello (IMO: 9442275, callsign: IBCO), a so-called 'anchor hoy'. It came flying out and just slowed to join the Kamarina. An anchor hoy usually serves oil rigs and other vessels that don't have a propulsion of their own. So, it appears that the anchor of the Ruby is fouled (stuck on the seafloor) and assistance is required to raise it. This now offers the explanation as to why she didn't leave immediately given the ETA displayed.

5 hours later the anchor hoy 'Carlo Martello' is currently heading back to port after staying alongside the Kamarina for a while - where they probably exchanged details on the current situation.

2 hours later (16:03 UTC+1) Ruby's position hasn't changed in the last hours. She's still at the same distance to the windpark as before. Amber II is still in port - by now at her 3rd position - in an area where other tugs are moored as well. The anchor hoy Carlo Martello will arrive in Rotterdam in approx. 1 h 10 mins.

At 20:34 (UTC+1) the wind (11 kn from the NW) has already turned and apparently, that is enough to keep her stable at the moment. She's at 1.2 NM from the restricted zone but appears to be south of her anchor. That means that winds are pushing her away from the windpark. The anchor hoy is moored right next to the Amber II,

2024-10-02

There's no movement at all in regards to the tugs. They are all where they were last night and no others appear to be heading out. The Ruby is moving ever so slightly away from the windpark. Given that Ruby's situation looks stable for the next 3 days, today included, there's still time. The only thing to consider is that - every vessel heading out to her would take around 10+ hours to get to her. She's 125 NM from Rotterdam.

At 12:00 (UTC+1) the tanker Waterboot 12 (ENI: 2314461, callsign: PF2323) appeared besides Carlo Martello and Amber II. Shortly afterwards, the custom's vessel Albatros (ENI: 2316862 callsign: PH7739) appeared next to the tanker. It left after 15 mins. One hour later, the tanker left as well. At 18:35 (UTC+1), Carlo Martello moved to a new mooring site in the same dock and shortly afterwards tanker Hilda S (ENI: 2338005, callsign: PF6761) arrived and she left at 22:00 (UTC+1).

Carlo Martello in the night, A bit later than expected - and, surprise, not heading for the 'Ruby' but instead to a port named Nordenham in the North of Germany, ETA tomorrow 16:18 LT (local time) - which might change depending on the tide. The status is displayed as 'Restricted Manoeuverability' and the speed is relatively slow for such a powerful tug.

2024-10-03

An article by The Isle of Thanet News clarifies that Ruby ran aground in Norwegian waters.

2024-10-04

At 19:49 (UTC+1) Carlo Martello is just now heading into port,arrived in Nordenham late in the night. Apparently dropped off the heavy cargo and more or less immediately left again - traveling back to Rotterdam at a much more normal speed for that kind of vessel and no longer displaying the status 'Restricted Manoeuverability'.

2024-10-05

Kamarina keeps standing by. Ruby has drifted farther north. As of this moment, she's roughly 0.1 NM closer to the windpark than before.

2024-10-06

Ruby's position with regard to the windpark has stayed rather stable over the last 24 hrs. A new interesting development is that Ruby finally appears to finally have found someone willing to help with the damage she suffernd during the grounding. The unlikely hero is a small marine services company from Kent who went out to meet her and - apparently did a first inspection of her rudder today. After a short time at her stern, the vessel returned to port. Carlo Martello and Amber II are, once again, moored side-by-side in Rotterdam.

2024-10-28

MV Ruby docks at Great Yarmouth Port, marking the end of this ship’s journey.

In-depth analysis

Provided kindly by Discord user trackerbell_4114 with light editing from me.

I feel the need to elaborate on a few things that aren't said anywhere. Industry press articles likely don’t talk about it because it’s obvious to their audience. However, normal people now learning through daily newspapers about the vessel won’t find this information anywhere. This leads to misunderstandings and – in my opinion – overblown fears. I am going to this length because I feel that, while certainly (at times) well-intentioned, the reporting is drifting heavily into the realm of disinformation by causing emotional responses to facts that can be reasonably explained. It just takes a bit more knowledge to sift through the finer detail to see more clearly. So, I’ll try my best to fill the gaps that I’m seeing. First of all, it is now clear that Fortuna III was on site for bunkering. The tug Kamarina obviously had taken the place of the tug (Amber II) that had accompanied the Ruby to this spot off the British coast. At present, the Amber II is still docked at Rotterdam, but I expect her – or another tug - to return and accompany the Ruby on her further voyage. Seeing the historic track of the Kamarina and the Fortuna III in conjunction with Ruby’s timing was the initial giveaway that indicated what was going to happen. The Fortuna can carry 2 different types of fuel, so it is not obvious, which kind was transferred. I am guessing that they topped off – either because the coming voyage is longer than the initially planned one, or they want to play it safe and have ‘reserves’ in case they end up somewhere offshore and need to remain in a waiting position for an extended time period.

Usually, the only time a ship’s engine is really shut off is when they are at berth – i.e. docked in a harbor. In all other circumstances, even at anchor or drifting, the engines will be running. They’ll run extremely slowly, but they’ll run. And they’ll consume fuel. At anchor, they run because they often need to put tension on the anchor chain to hold the position. While drifting, they keep adjusting their course because winds, currents and tides push the vessels from their location. So, unless a vessel is firmly attached to something that really doesn’t move one bit, the engines are running. Now to the accident: accidents happen all the time. Big and small ones. Running aground is more common than most people realize – because only the really big cases make the news. Hull damage can occur for various reasons. Sometimes ships strike things floating in the water, like lost containers or other unknown obstacles. Hull damage in modern tankers isn’t that dramatic anymore since all the newly built vessels have double hulls. Older, single-hull vessels are at a much greater risk of experiencing catastrophic damages when hitting an obstacle. Anyone who has ever seen a detailed map used by navigators will quickly realize that the sea isn’t always as deep as one thinks – and that there are lots and lots of known – but sometimes also unknown obstacles. To give an example: parts of the English Channel are only +/- 5 m deep. Those areas are closed for large ships – but, in the event of a major storm, a ship could veer off course and end up hitting the seafloor in the middle of the channel.

Besides the obvious obstacles in the sea, there are also sometimes floating obstacles such as debris, lost cargo like shipping containers, or even whales. I don’t have access to the relevant maps and accident details pertaining to the Ruby, but a bad storm can get literally every vessel into trouble. When winds and high waves are pushing the structure into a certain direction – accidents do happen. To anyone who’s interested in learning more: there are real-time weather maps including wave height available online. We’re heading into winter and storms up North can be really bad with waves that are often 10 m in height. That’s everything BUT smooth sailing. So, while there are reckless masters out there, most crews do want to come home safe and sound. A bad storm is always something you try to survive. You’ll never control your ship 100% during a storm. You live from wave to wave.

It was argued that the Ruby could have stopped at Murmansk for repairs. Yes, the Ruby passed the last Russian port it – theoretically - could have stopped at. However, Murmansk is not only the base of Russia’s nuclear submarine fleet but also a harbor with a number of crude oil terminals. Every day, several VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers) – i. e. huge takers measuring 400+ m in length - are at those terminals.

While no one will likely ever find out if the Murmansk port authority was contacted and what their reply might have been, the above 2 points could explain why it did not stop there. The other would be that Russia desperately needs Murmansk as a port. It is of a huge strategic importance and I doubt anyone would run the risk of destroying the harbor to salvage a ship like the Ruby. Also, Murmansk lies farther inland. It’s not immediately accessible from the open sea. The actual port of Murmansk lies approx. 35 NM inland – and there’s no getting there in a straight line. With the Ruby already having rudder problems – plus the weather - it would have represented a huge risk to try and access the port. But, most of all, I doubt anyone wants the explosive cargo anywhere near nuclear vessels or oil terminals. What I am not completely clear on is whether Murmansk would even have had the facilities to unload and repair the Ruby at all. And that leads to the next point: The Ruby has to be unloaded in order to be repaired. Usually a hull damage requires welding and that’s a big NO-NO, when there’s such a cargo on board. To unload such a cargo, you need the right equipment, storage facilities, trained personnel and – these days – all kinds of licenses. It’s not like unloading a pile of scrap metal or sand by whatever means possible. Tromsø was the next – and nearest possible destination.

Norway ultimately sent her on her way again for a variety of very valid reasons – but they also examined the ship to ascertain the Ruby was seaworthy – even with difficulty. The next intended destination was Klaipeda in Lithuania. The port of Klaipeda is very narrow. There’s no room for error and the main cargo is – besides fertilizers – LNG, oil but also containers and grains. Stepping back and ignoring the heightened risk due to huge fertilizer silos and LNG or oil terminals, one also has to consider that Klaipeda is of strategic importance to provide goods to the Baltic countries. It’s also vital for the fleets of the 3 Baltic countries in light of the situation with Russia. If a port like Klaipeda got destroyed, the power dynamics between Russia and – likely not only – Lithuania would be greatly impacted. So, I absolutely don’t blame them for refusing. But – before the Ruby could ever get to Lithuania, she would have needed to pass through the Great Belt. That’s a very tricky route with a ship that has rudder trouble – and there’s a lot of traffic. So, I don’t blame Denmark and Sweden either for refusing. Malta’s refusal also makes a lot of sense. Malta is a tiny island and Valetta’s shipyard lies smack-dab in the middle of Valetta. I absolutely understand that they want Ruby to unload her cargo before heading into their port.

There’s no easy answer to the situation. So – since it was clear that the Ruby couldn’t head into the Baltic, they went looking elsewhere. There are some usual suspects when it comes to repairs like this. Many are way too far away, so they’ll have to improvise – and quickly, because winter is coming. I’m absolutely convinced that they got a lot more negative answers from ports than is now known. However, they did manage to organize the bunkering off the British coast – before heading into the Channel. This link explains in relatively broad strokes what bunkering actually means. What is not made clear enough, though, is the fact that, once bunkering has started, there's no quick aborting it. Any bunkering or ship-to-ship transfer (STS) performed at sea is always an extremely risky undertaking. During bunkering, both ships are pretty much 'stuck together’, because they have to be firmly attached, meaning, they can't separate on the fly if necessary. They are then also unable to maneuver normally and they will signal that to their environment by changing their AIS status, flags, light and sound signal. Any and all traffic around them will have to stay clear of them as they will be unable to maneuver to get out of the way of anything or anyone – which is why there are such strict rules for where and under what circumstances STS is allowed. While all this sounds highly risky, bunkering is usually done under completely different circumstances than in this present case. Every ship has to bunker regularly, or else they couldn’t operate. However, it is usually done inside the harbor or in an anchorage zone – where risks can be mitigated.

STS of crude oil is usually done at sea, as there will be huge tankers stuck to each other for a day or two during the whole procedure. They also won’t be at anchor but slowly moving in some sort of a circular motion in a defined area. This is done away from shipping lanes and anchorages to avoid running into trouble. They will then also display ‘Restricted maneuverability’ which informs other vessels that they have to steer clear of them. STS as such, though, is not bunkering. But, I’m mentioning it because the risks are similar and in the case of the Ruby, it’s a bunkering that looks a bit like an STS. I dare say, that bunkering at this exact same spot just off the coast of Kent is probably a first in history – and it won’t take a sophisticated guess that without a very clear permission to do so, this would not be possible at all. While there is no reporting on any such permission, I believe that someone made an exception – not least because of the environmental risk. Otherwise, the ship would have been surrounded by lots of ‘official ones’ in no time. The Ruby is currently roughly 14 NM off the coast of Kent and a minimum of 6 NM from any shipping lanes or wind parks. Under normal circumstances, an STS or bunkering wouldn't be allowed in this area at all. Period. However, the situation is as far from normal as it gets. In order for the Ruby to be able to continue, she must bunker.

What’s bugging me is that newspapers are, however, just basically saying that ‘this ship that can blow up just stopped outside our door’. And yes, of course, the Ruby carries a high-risk cargo, but the mood that this kind of reporting is creating is neither helpful nor good. Dangerous cargo like this passes through waterways near land many times each day. There’s always a risk. And – thanks to ShuckyDucky’s link it is easily verifiable that all certificates regarding the technical inspections of the Ruby are current and valid. So, apart from having had an accident, the Ruby is in proper condition – which has also been confirmed by Norway. I think it’s realistic for the Ruby to head to Las Palmas. Fertilizer is a common cargo at the port and there’s a shipyard offering the required services. On top of that, the port is very easily accessible without all the intricate navigating that would have been required in the other ports. So, that’s it. What should, however, also be said is this: there’s crew onboard the Ruby, probably around 15. What most people don’t know is that, if anything goes wrong, the crew is considered responsible for what happened. Not that they have to literally all pay damages, but they can get arrested – provided they survive the incident. Many times, after accidents, a ship’s officers or at least the Master, get arrested and sued in court. Apart from that, they often work under very difficult circumstances, meaning that the companies running the ships will ask impossible and illegal things from them. It’s often do-or-die kind of job. Say no and you don’t get the job. Say yes, and you’re in trouble when things go wrong.

The last thing that always remains a threat to the crew is that, when a ship runs into trouble, there are owners who literally jump ship on their crews. That means that, from one second to the next, there’s no one in charge of the bills for the ship, insurance, port or passage fees, fuel bills or the pay slips or insurance of the crew. There are ships at anchor in different places of the world, where crews can’t leave the ship because of such a situation. They’re stuck on the ship. It’s worth taking the time to read these stories. They are harrowing tales. This is just one example. Last but not least, COVID has taken a serious toll on all crews around the world. There were many cases where crews did not or could not change after their time was up and they stayed onboard the same ship for sometimes up to 3 years. Being onboard a ship like the Ruby is a huge challenge for your mental health. And in the meantime, the press is going haywire.

If you look at the various available maps of Kandalaksha, you find - a lot of nothing, except railroad lines and a big section for coal loading. With the imagery I saw thus far, I am wondering how they even loaded Ruby's cargo. Current satellite imagery probably helps, but I haven't dug that far yet. From what I am seeing now, there are no silos or other storage facilities that aren’t used for coal. So, my sophisticated guess is that they load the ammonium nitrate directly from the cargo trains by using suction cranes. Consequently, the question is: where would you unload the ships cargo to, once the train has left? There are various sites explaining the storage requirements for ammonium nitrate. What they would be in Russia is probably a good question. However, I still believe that they currently only have loading capacity at the port and no fertilizer storage facilities. Maybe someone can find relevant satellite imagery proving that. Furthermore, what I’m missing is a dry dock. Depending on the extent of the damage, that may be required for repairs.

Depending on where the hull is damaged, the effect may be minor on the ships capacity to sail. Most people immediately think of sea water flowing freely into the ship. While that’s a possibility, depending on where the damage is located, it appears to be in an area where pumps can be used to get the water out. On the other hand, while still technically a ‘monohull’, all those ships have ballast tanks. This link explains where those tanks are typically located in the different ship types. So, taking the example shown here, if the Ruby sustained damage in the areas where the ballast tanks are located, she’s able to evacuate incoming seawater via the ballast pumps. While that’s certainly not a long-term solution, it does help her seaworthiness. What’s more relevant though, is the question regarding the integrity of the overall hull structure after the damage. Because that can get a lot more dangerous very quickly in the wrong kind of weather. Here’s a video that explains the shear force and bending moments in vessels.

Since the Ruby was deemed seaworthy, the damage must be in an uncritical location and can wait to be repaired.

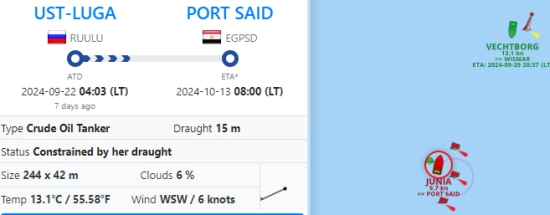

In one of the articles, the reasoning for Denmark and Sweden to not allow the Ruby to pass through the Big Belt supposedly was her draught currently indicated as being 10 m. To those unfamiliar: the draught indicates how deep a vessel lies in the water. That, however, is no valid reason in the case of Ruby. Every day, vessels twice her size with a lot more draught go through the Big Belt without difficulty. Right now, there are some good examples at this exact location: The Junia for instance has a draught of 15 m. Her status therefore is 'Constrained by her draught', which means that she has to stay in the middle of whatever shipping lanes she's in to benefit from the maximum depth of the water. At the same time, it indicates to vessels in the vicinity, that they must change course, so she can stay her course. This status is one of the very few exceptions allowing a ship to not change course to avoid collision. Collision avoidance then becomes the responsibility of all other vessels. Just north of Junia is Fjord Seal with the same status and also 14.8 m of draught. So, in contrast to what the news article said, the draught wasn't the reason for her not being allowed to pass through the Big Belt.

October analysis

At the bottom in Diagram 1, you see Ruby's (approximate) initial position and her (approximate) current position. The 2 blue ovals mark 2 wrecks. The highest point of the wreck on the right is at a depth of 34.9 m. The highest point of the wreck on the left is at a depth of 21.6 m. Water depth along Ruby's drift was ranging around 35 meters for the most of her drift. Now, she's in approx. 20 m of water. If she drifted in a straight line, she would have avoided the wrecks. Unfortunately, I cannot plot her path far enough into the past to show her exact movements. But, either way, she might have hit one of the wrecks. Maybe there will be news about what happened at some point. The other and far more troubling issue is that, along her path - and no matter what exactly her path was during her drift with the anchor down - she crossed 2 submarine cables - identified in the chart by the line with the wave and the lightning shape indicates them as high-voltage power cables. But - hold your horses: If she had destroyed the cables, we would probably have known by now - but maybe there's damage. It's 'wait-and-see' on that one. I don't want to speculate that she damaged anything. And she can't have dragged any of those cables to her current position. Her movement would have stopped much earlier if she was tangled up in the cable. If she got lucky, her anchor just slipped over them. But - in light of past events of this kind - it's worth mentioning. So, now back to the explanation regarding her anchor trouble.

No ship with a crew in their right mind would willingly drag an anchor across any distance like that. For sure not in a spot like this. So, it appears obvious that the Ruby is unable to raise her anchor. And given the fact that an anchor hoy appeared, the trouble must be an 'underwater issue' and not onboard the Ruby. Otherwise, another kind of ship would have approached the Ruby for repairs onboard. Now, why didn't the anchor hoy just stay and solve the problem? The map shows the composition of the sea floor. It appears that, thus far, the Ruby was lucky and only had sand, shells and pebbles underneath her. The boulders are to her north. It appears unlikely that her anchor got fouled due to boulders. It could still be a boulder - but we'll have to wait and see to find out if any information on this is made public. Listening in on channel 16 would be very interesting at the moment. I've tried, but I can't receive a clear enough signal. Besides boulders, though, there are lots of other possible things that could have fouled her anchor. Obviously, parts of the wrecks, but besides that also nets or maybe even other anchors/chains. The only thing that appears obvious at this point is that - while she actually needs to be well on her way to Malta - she's still there and drifting with the anchor down. Now, what about the anchor hoy returning to port? I am guessing that it is returning to port to retrieve additional material. Normally, an anchor hoy carries all the equipment necessary - however, it could be that they need some specific equipment - and potentially a diver. The water depth at Ruby's position would easily allow for diving. Since the anchor hoy isn't 'racing' back to port, I imagine that they called ahead and while they are going back to port at a normal speed, the dive crew is getting their gear ready. What is vital to understand is that, while to anyone spending his entire life onshore, all this sounds really ominous, someone who has spent enough time at sea will confirm that these things aren't so uncommon. People outside the industry just never find out, unless it makes international news. So, what I am writing is the result of meticulous analysis of the available data from industry sources - mainly because there will never be anything published by the press about what happened in detail. In order to understand the processes, you need to closely watch every move of known and unknown parties, conditions on site and in the vicinity - and then draw conclusions following the rules of the business, calculations, etc. and comparing that to past experience. Anyone looking at such charts for the first time will likely see lots of things that make strictly no sense. However, if you analyze things in detail, what's displayed becomes much clearer. It's simply like watching a foreign movie with or without subtitles. Nautical science is a highly complex field with a huge amount of special knowledge. You have to acquire a lot of very different skills in order to be able to work in the field. And to add my own disclaimer: while some might take my choice of words, when I'm saying 'I'm guessing' or 'most likely' or 'apparently', etc., as pure speculation, it is far from that. Everything I say is the result of data analysis. But, obviously, I cannot claim 100% that a particular thing will happen or has happened, if we'll never receive the physical proof for it (which we most likely never will). But, viewed with 'seeing eyes', you recognize valuable indicators for what's actually going on. And it helps disarm false or incomplete information in the press - and, thus, also remedies false perceptions of the situation as such.

2024-10-03

Carlo Martello is a powerful tug. For this tug to display a 'Restricted Manoeuverability' status, it must either carry or pull a very heavy cargo - I think it is carrying it given the mooring and departure situation last night. Both scenarios, however, would explain the status. So, wondering what the tug might be carrying, and taking a step back to look at the whole picture, I am starting to believe that 'Ruby' might have lost an anchor and maybe even the chain that goes with it. Ruby has 2 anchors. it would not make sense to even try and begin to calculate whether that may be the reason why she's moving at anchor the way she does. However, it could explain the situation as such. Now, anticipating a scenario where the she has lost one of her anchors, maybe including the chain, it would explain, not only her movement, but also, why customs appeared yesterday and why the anchor hoy is heading for Nordenham. In and around Nordenham you can find several large shipbuilding companies. If a new anchor was ordered, it could be that Carlo Martello is headed there to pick it up.But, if that's the case, why the status 'Restricted Manoeuverability'. The only possible scenario that I can come up with is that, the anchor and possibly the chain ar onboard the 'Carlo Martello'. 'Amber II', the original tug that accompanied 'Ruby' from Norway, is also an anchor hoy. When 'Carlo Martello' returned to port, it spent most of the time alongside the 'Amber II'. Maybe the 'Amber II' originally managed to retrieve the chain - but not the anchor. Or, she even retrieved both but a vital part broke that needs repairing. So, either way: customs appeared. As seems clear now, not for extra crew. However, since 'Ruby' is outside of the EU and UK waters - and will travel on to other locations, she needs customs documents and certificates, if a newly (expensive) item is on board - like for instance a new anchor and chain. It's an export scenario. Last night, when I mentioned that 'Carlo Martello' appeared to be ready to go, it was still moored but the engine were running. For a moment, it moved sideways at the mooring spot - and then the engine was turned off again. That could have been the moment, when something heavy was loaded onto the tug. Turning on the engine helped it stay in place while the heavy cargo was lifted onboard from the side. 'Carlo Martello' only left approx. 2 hrs later.

If the Amber II retrieved the chain, Carlo Martello could have taken it to Nordenham for it to be fitted with a new anchor. Given the fact that she should be low in the water due to her cargo, I doubt that this first inspection by the Kent marine small business delivered any results to determine further steps, as neither rudder nor parts of the propeller should be visible from above the waterline. I would think that they'll be back for a more in-depth assessment with appropriate equipment and possibly divers.