Mankato Grows Up: Keeping ScOR #15

The other week I had reason to visit my hometown in the Upper Midwest. Some of you will remember that I was raised in Mankato, Minnesota, a college town 80 miles from Minneapolis. Which you know because you’ve heard me talk about it in “Little War on the Prairie,” a documentary I originally made for This American Life in 2012 and repurposed for Scene on Radio’s Seeing White series in 2017.

The piece tells the story of the U.S-Dakota War of 1862, a bloody conflict that culminated in the largest mass-execution in U.S. history, right there in Mankato: the hanging of 38 Dakota (Sioux) warriors.

“Little War” explored the American habit of willful historical forgetting. An important theme was the fact that I could grow up a century later in the very place where these dramatic events happened – events that were pivotal in the history of my home state – and hear scarcely a murmur about them during my entire childhood and schooling there.

Going back to Mankato in 2025 got me thinking about how much has changed since I was a kid – and about this country’s newest war on historical truth-telling.

*

The U.S.-Dakota War was calamitous for the Dakota people, for whom Mni Sóta Makoce – the land where the water reflects the skies – has been home for at least a thousand years. The U.S. government extracted land from the Dakotas in the 1850s — roughly the southern half of today’s Minnesota — through a coercive and deceptive treaty process. This paved the way for Minnesota to claim statehood in 1858. The Dakota people were corralled onto a narrow reservation. In 1850, Indigenous people (Dakota and Ojibwe) outnumbered European settlers by five to one in Minnesota Territory. Just a decade later, so many White people had flocked in that it was the other way around.

War broke out in 1862. That August, the Dakota people were facing starvation because the U.S. government had not delivered annual food shipments as promised in the treaties. In desperation and anger, some Dakota warriors rose up and attacked settlers along the Minnesota River Valley, killing hundreds. The U.S. Army was busy with a much bigger war in the American South, but it mounted a force that defeated the Dakota fighters within weeks.

Then came the payback: Dakota people were marched into camps, where many died of cold and disease. The survivors were expelled from the state. The government convicted hundreds of Dakota warriors in quick military trials. After an intervention by President Lincoln, 38 were hanged in Mankato’s town square, the day after Christmas, 1862.

My family moved to Mankato in 1967, when I was six years old and entering first grade. I got through high school without learning about the U.S.-Dakota War or the hangings. As I told Ira Glass in “Little War,” I don’t recall the subject ever coming up in any conversation I was privy to. These defining events were almost entirely absent from the story White Minnesotans told about ourselves and our home.

*

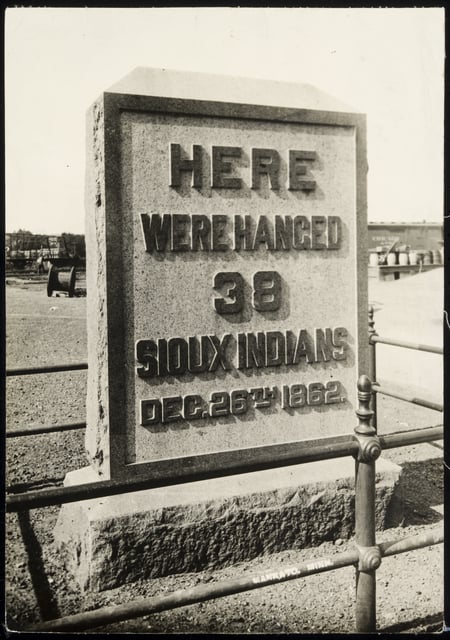

It's not that Mankato had never publicly acknowledged 1862. On the fiftieth anniversary of the hangings, in 1912, the city unveiled a granite monument on a downtown street corner. It looked like a six-foot-tall gravestone engraved with these blunt words: HERE WERE HANGED 38 SIOUX INDIANS DEC 26TH 1862.

A speaker at the dedication felt the need to say that the monument “had not been erected to gloat over the deaths of the redmen,” as the Mankato Free Press put it at the time. But many saw the marker as sending a triumphalist message. The famous lawyer Clarence Darrow came through Mankato in 1927 and reportedly remarked, “I would never believe that the people of a civilized community would want to commemorate such an atrocious crime.”

I’ve since learned that when my family moved to town in the 1960s, the 1912 monument still stood in its original spot. But the built landscape surrounding it had been transformed. The marker now stood inconspicuously in the corner of a gas station parking lot. I have no memory of seeing it or knowing it was there. In the face of protests by the American Indian Movement – and a growing sense among local White leaders that the monument and what it commemorated were nothing to be proud of – the city removed the eyesore in 1971.

This was the Mankato I grew up in: a city proud to be the site of the Minnesota Vikings’ annual summer training camp – and eager to pretend 1862 never happened.

But that was then.

Acknowledgment

Today, a hard-to-miss monument, in the form of a 67-ton stone sculpture of a buffalo, stands in a small plaza dubbed Reconciliation Park at the site of the hangings in downtown Mankato. A commemoration led by the Dakota community fills the streets there annually on December 26.

Another monument, including a plaque and a sculpture of a Native man, called “Winter Warrior,” stands across the street outside the Blue Earth County Public Library.

Every September, the Dakota tribe hosts the Mahkato Wacipi, a powwow honoring the Dakota 38 and open to all, in a park along the Minnesota River. The city of Mankato designated the site as the location for the powwow and invited Dakota elders to name it: Dakota Wokiksuye Makoce – Land of Memories Park. The first day of the powwow, Education Day, is reserved for hundreds of third graders from nearby schools to attend and learn about Dakota culture.

Fifteen miles north of Mankato, just outside St. Peter, Minn., is the Traverse Des Sioux Treaty Site History Center. The museum tells, thoroughly and accurately, the story of the treaty signed there in 1851 – a treaty so unjust to the Dakota people that it set the stage for the U.S.-Dakota War.

In Minnesota’s public schools, a two-week unit on that war, covering its causes and its devastating effects, is required for all 6th grade students.

This is not to suggest that the work is done. Minnesotans could and should do more to ensure that the story of 1862 is more deeply and widely known. Even more importantly, the state and the nation should take bolder steps to right the centuries of injustice and violence done to Indigenous Americans.

Still, Mankato has come a long way since my childhood years.

These days, with all the shouting about the allegedly novel and radical invention called wokeness, younger people especially could be forgiven for thinking that antiracism efforts and the push for historical truth-telling only emerged during the Obama years — or even after the murder of George Floyd. But a steady movement among historians, educators, and activists for more honest U.S. history gained momentum much earlier. The above efforts at acknowledgment and reconciliation in and near Mankato took place over decades.

Somehow, despite these acts of wanton wokeness and “Radical Indoctrination,” my hometown is doing just fine. Life goes on. People drive and stroll down Mankato’s Riverfront Drive past Reconciliation Park and that larger-than-life buffalo, and some, no doubt, are reminded of what happened there in 1862. And yet they proceed to their office or the supermarket. They don’t go straight home and curl up in bed, disabled by self-loathing and hatred of America. Children of all shades, after learning about Native culture and the U.S.-Dakota War, go on with their day feeling OK about themselves.

On my recent visit to Mankato I gave brief remarks at an event, and I alluded to all of this. Mankato, I said, should be proud of its acts of truth-telling. They’re signs of a community that’s grown more mature, more healthy, more willing to confront its complicated past so it can do better in the present and future.

Getting over ourselves

Among its many attempts to turn back the clock, the Trump regime has prioritized its drive to reclaim a pre-1960s, America-can-do-no-wrong approach to U.S. history. Just days after retaking office, Trump signed an executive order instructing the Education Department to impose penalties on schools that stray from “patriotic education.” He’s ordered that National Park Service exhibits be stripped of many references to LGBTQ people, women, and non-White folks, and griped that the Smithsonian says too much about “how bad slavery was.”

There are many words for people who adopt this posture toward their own national story. One that we don’t use enough is … coward.

I recently heard a Buddhist teacher say this: “What is not me cannot be a cause for shame.” He was talking about personal trauma, the way that human beings tend to carry shame about painful parts of our past – whether the trauma came from someone harming us or from our harming others. To heal, the teacher said, we need to face the past and learn what these painful episodes have to teach us. Whether the message is “that shouldn’t have been done to me” or “I shouldn’t have done that,” we can, over time, take the lesson on board and then detach ourselves – accept that something bad happened but it no longer defines us. In cases where we or our forebears were the perpetrators, an important step is renunciation. To say simply: That was wrong.

So many times I’ve scratched my head: Why, exactly, are so many of my fellow (White) Americans so stubbornly resistant to this? Why do they fume at every mention of settler colonialism, slavery, genocide, White supremacy? These are facts of American history.

Is it because they imagine they would have done these things given the chance? Or because their ancestors took part and they want to defend their forebears’ honor and reputation? Is it because they want to protect the advantages that have accrued to people who look like them thanks to these crimes? Or because they identify so strongly with a subset of humanity – White America, let’s say – that they experience criticism of the group’s prominent members as a personal attack? Are they afraid that if we White Americans admit to these crimes, and lift our boots off the necks of the peoples our country has oppressed and exploited for so long, that we’ll then have to take our place on the receiving end?

May the day come, and soon, when a critical mass of Americans find themselves able to, for heaven’s sake, let it go. Put down those burdens and fears. Be more like the people of Mankato, Minnesota. It’ll be all right.

The truth will set us free. Then we can more effectively do the work of setting things right.

If you missed past newsletters, find the archive here.

Know someone who might like Keeping ScOR? Please forward this to them!

-

Excellent essay! Thank you for writing and sharing your perspectives! I've linked to this essay in one of my blog posts (https://deep-roots.blog/2025/11/11/notes-from-the-heartland-part-5-home/)

-

Thank you for the article John! Very insightful!

-

So good and I have a big question. Sent you an email. many many thanks.

Add a comment: