“Savoir-faire essentiel"

The striking accompanists of the major French conservatories have a signed petition of support from 1400 musician colleagues. Could such a thing happen in the United States?

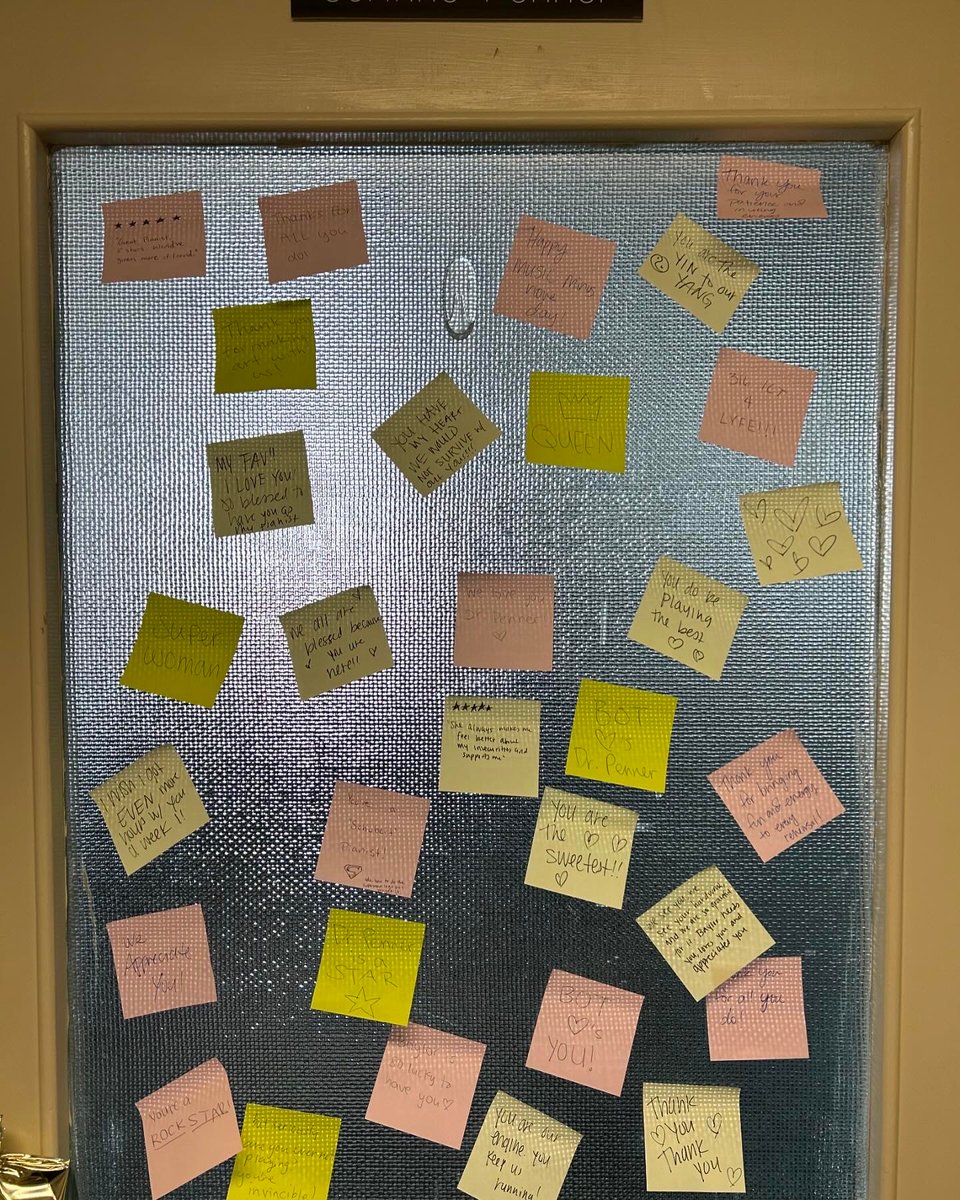

Many of you know that this newsletter is named for a fun project I got going last September. Music Minus None was originally an Instagram page dedicated to showing appreciation for accompanists/collaborative pianists. We ended up choosing September 18 as Music Minus None Day, a chance to shout out collabs across the country, and we got pretty good participation for our first try. People at about 150 colleges, conservatories, and universities posted pictures of their pianists, brought them snacks and cards at work, and shared praise for them on social media. Some administrations got into the act too. My school, Baylor, was one that showed up and showed out (among other things, the students in the vocal department covered the pianists’ office doors with loving messages on Post-Its). The whole day was celebratory, in some ways more than I dreamed.

But in all honesty, it wasn’t what I’d originally hoped for. For a couple of years now, in various colleague groups, I’ve been sending up the trial balloon of a one-day general strike for accompanists. Just one day where all the collaborative pianists stay home, to make a point about how essential we are to all of our institutions. We could even pick a day well clear of auditions, juries, or recitals, making sure we caused disruption and inconvenience rather than pain.

As we say in Texas, that dog would not hunt.

But in France, the pianistes accompagnateurs have gotten their grève on. For the last two weeks, the collaborative pianists of the Paris and Lyon conservatories have been on strike. This comes not three months after “L’accompagnement, l’autre voix,” a conference at the National (Paris) Conservatory focussing on the various specialties within the profession of accompanying. I wonder how much that gathering served to build inspiration and solidarity. In a February 13 interview with Radio France, National Conservatory pianist Bertille Monsellier said, “We are important people, and we are not used to saying it out loud.”

The pianists are not alone in raising their voices. A significant number of fellow faculty have walked off the job in support; the figure from that Radio France interview two weeks ago was 34% of the faculty in Paris. An additional 1400 musicians have signed a petition in support of the accompanists, among them conductors, singers, composers, and fellow pianists. They write, as reported in the French industry publication Diapason:

“We want to remind you here that their artistic, pedagogical and human know-how is essential to our entire profession. It cannot continue to be so little recognized and so poorly valued…finally regularizing a situation that raises great questions, and which keeps these artists in an unworthy precariousness and a shocking lack of consideration, must be an absolute priority.”

The “situation that raises great questions” is the fact that accompanists’ compensation at the two major conservatories has been capped for over a decade at about half that of their teaching colleagues. And, according to an article in Le canard enchaîné, the first two rungs of the accompanists’ payscale are below the country’s minimum wage.

In a letter, the accompanists wrote

"How can we justify that by working in these two prestigious higher education institutions, we would be less paid and considered than some of our colleagues, supervisors and instrumentalists at the initial teaching conservatories?”

According to the Diapason article, “significant progress” is being made regarding the pianists’ demands.

Could it ever happen here?

The situation of the French pianists has plenty of parallels on our side of the pond. A cursory glance at public salary information from a couple of large Midwestern state universities reveals similar disparities of compensation to those described in the French press, full time staff accompanists making 50% or less of the average studio teacher. A firestorm erupted several years ago when a Facebook post outed the major New York conservatories’ shocking $20 per hour rate for accompaniment; another colleague told me how he battled administration to get their rate raised to $40 per hour. Within the last month, I’ve talked with voice teachers at two different large universities who despair over the upcoming retirements of the lone expert pianists in their departments, people who have stayed long in undercompensated positions for the sake of family ties. These friends doubt their departments can attract an equal level of expertise for the same money, and worry about whether their administrations will respond with better support.

Such disparities are certainly rooted in ideas of faculty versus staff: studio teachers are seen as artists and pedagogues, while accompanists provide a simpler kind of service. This is where the language from the French support petition is so significant:

“Leur savoir-faire artistique, pédagogique et humain est essentiel.”

“Their artistic, pedagogical, and human know-how is essential” - in other words, accompanists are artists, and teachers, and experts as well in human relations. Those words are powerful. They are true. We know it, and our partners know it.

And yet, we are not yet used to “saying it out loud,” like Bertille Monsellier, nor are our colleagues - at least not beyond the level of snacks and shout-outs. But it’s not because we don’t collectively know what’s right, or that we don’t care. There are many significant differences between France and here - the size of our country, the number of institutions, the lack of uniformity in structure, outcomes, and connection to industry, the difficulties and burdens of funding. The biggest one, I’m certain, is the absence of a real social safety net. We don’t have to look far to see how precarious things can get, and how fast.

I’ll take heart from our colleagues in France, pianists and non-pianists alike, and take a lesson from their risk and solidarity. Their wages have been stuck for almost twenty years: courage that comes slowly is still courage. The pull of the status quo is great even in peaceful times.

These are not exactly peaceful times.

So how do we find a dog that hunts?

Here’s what I know: I’ve got savoir-faire essentiel, and so do you. That’s worth standing up for and linking arms over. It’s worth naming what we know, what we do, why we do it. And maybe more than ever, it is absolutely crucial to name what your colleagues do, what they know, and why they matter.

Everybody on the front lines: pianists, musicians, citizens, friends.

Music Minus None forever.

Add a comment: