Period 34: Menstrualsplaining

How have I gotten thirty-four issues into this newsletter and not done a basic menstrual cycle explainer?

My whole book is kind of like a menstrual cycle explainer, so if you want the long version I’d recommend buying or borrowing it. But let me give you the short-ish version.

Endometrial production and differentiation

Over the course of the menstrual cycle – from one bleed to the next – one of the main things that is happening is the production of endometrial tissue. You’re growing the lining of your uterus, thanks in large part to estrogen. This typically occurs in the first half or more of the menstrual cycle.

So the tissue is getting thicker and thicker, but at a certain point the uterus is exposed to progesterone. This can happen because of ovulation or because of a hormonal treatment. Progesterone changes what the endometrium is doing: it goes from growing and growing to differentiating. I often liken it to transitioning from some kind of flatbread to a Thomas’s English muffin – lots of nooks and crannies.

This differentiation – moving from just getting more and more tissue to becoming a more specific tissue – does a few cool things. It limits endometrial growth, so it doesn’t overdo it; it creates an opportunity for the uterus to practice tissue differentiation, a good idea for an organ that’s going to have to do this even more comprehensively in pregnancy; and of course it does lay the groundwork for an actual pregnancy to occur under the right conditions.

The nooks and crannies are not just there to look cool. They contain nutrients to feed and support an embryo should it touch down, because at the start of pregnancy there is no placenta to coordinate feeding efforts. And they contain embryo sensing capabilities to see if the embryo is of the right quality that it is worth the investment (physiologically speaking).

In a cycle where ovulation happens (more on that in a moment) and there’s no embryo present, then the corpus luteum, the thing making the progesterone, starts to degrade. Progesterone peaks about three quarters of the way through the cycle, but then starts to decline because of that degradation. All the fun nook-and-cranny-making ceases because the endometrial tissue isn’t getting the signal to keep doing so – eventually this is significant enough that the tissue starts to break down and you start to see the intentional process of menstruation occur.

Menstruation

Menstruation is of course part of the broader endometrial cycle, but I want to devote a separate moment to it here just to say (as I’ve said before) that it’s not just a time where tissue breaks down, but also a time where tissue repairs. It’s a simultaneous process and that’s why menstrual effluent itself is so cool – it’s full of all sorts of healing chemicals because that fluid is part of what contributes to the menstrual healing process.

At various moments in our lives, and because of various environmental pressures or genetic inheritances, we end up with really variable amounts of menstrual blood. It also varies a lot in how many clots you find yourself passing – much of which is actual endometrial tissue you are sloughing off.

Ovulation

For a lot of folks this is something that happens most menstrual cycles. But it’s not a guarantee or inevitability, and there are certain factors that make it less likely. So we need to stop always acting as though ovulation is an assumed part of the menstrual cycle.

There are many things that decrease the chances of ovulating (releasing a dominant follicle, often called an egg, from the ovary), like having polycystic ovarian syndrome, not meeting your energetic needs by eating less than you expend, or getting older. Other stressful circumstances may also affect ovulation, but it hasn’t been super well studied: what we do know is short term, moderate stress doesn’t seem to do much, but chronic or especially big stressors might.

The process of the next ovulation starts as soon as the last one hands – just like endometrial cycles, but offset. The process that leads to selection of a dominant follicle is more or less continuous and occurs in waves. I’ve written about this back in issue #9 so feel free to head there for more detail.

How does it all come together?

Now I will briefly explain the hormones!

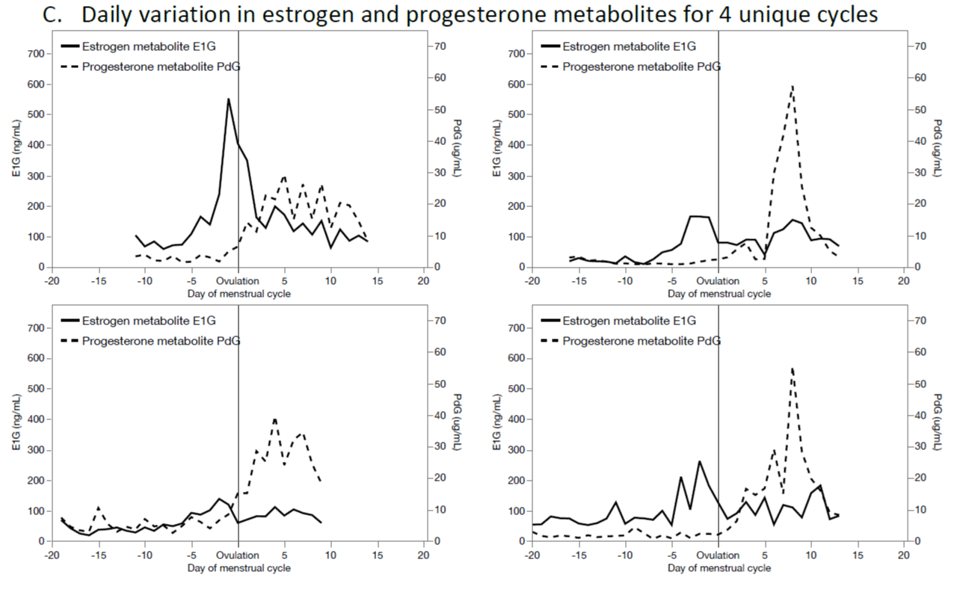

Rather than insist upon one normative way the hormones of the menstrual cycle look for everyone – something that simply isn’t true – I’m going to show you four different cycles from hormone analyses from our own lab. This is an image from a book chapter co-authored by Dr. Mary Rogers-LaVanne and me:

I’ve already reduced some of the variation from our sample with this image, because all four of these cycles are ovulatory – mainly because it’s only with ovulatory cycles that you can show what’s going on with progesterone.

What I can say is that for most ovulatory cycles estrogen goes up through the first half of the cycle, peaks at midcycle, and then sort of follows the progesterone peak in the latter half. This hormone is important for growth of endometrial tissue and for coordination of the follicle waves that lead to ovulation. Progesterone has a swell through the latter half of the cycle, though because of the way hormone production works small amounts can come from other places, so you do see small amounts in the first half as well.

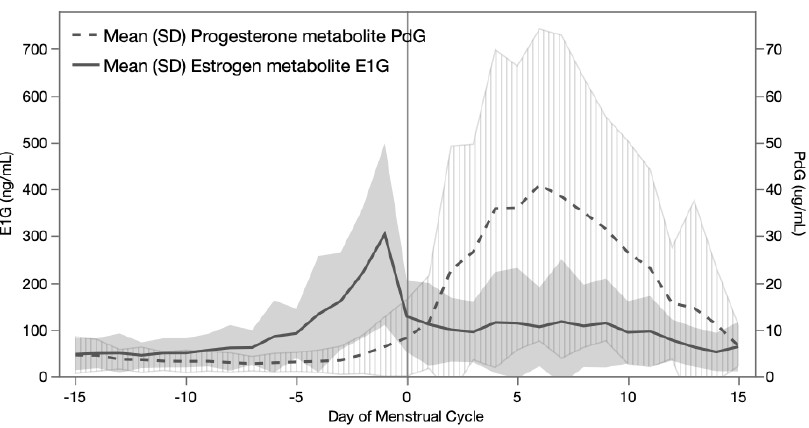

But the actual shape of these curves? The height of the peaks? They are not the same. They only look like the one you see in health textbooks if you average a whole bunch of cycles together:

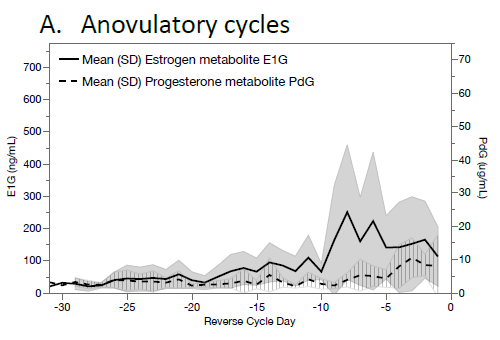

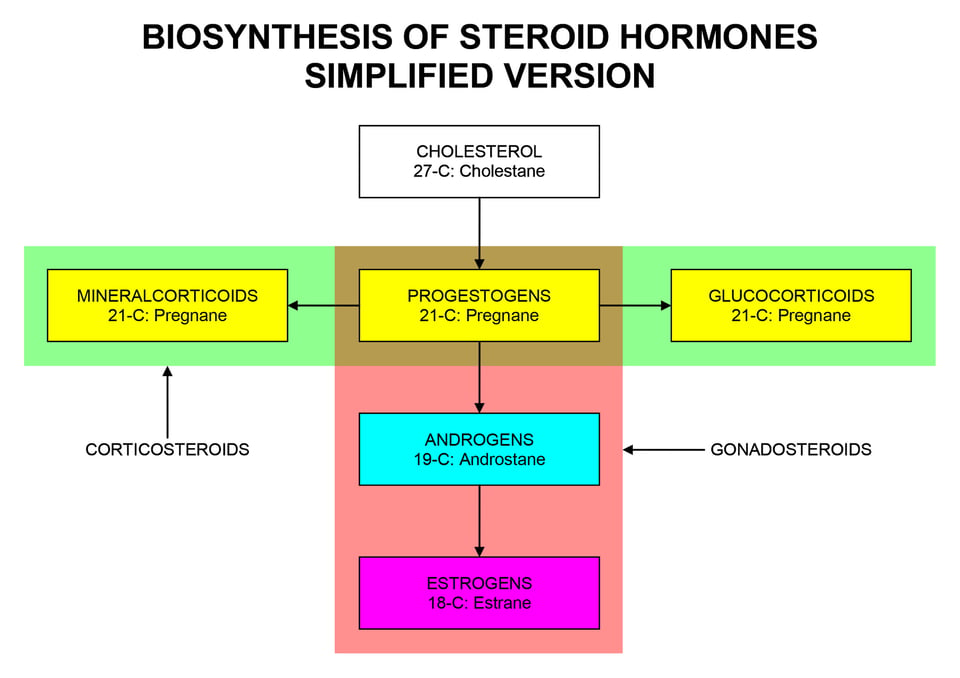

For anovulatory cycles you tend to see a lot more unopposed estrogen. The corpus luteum I have mentioned a few times is what’s left behind when ovulation happens; that’s what makes progesterone. Without a corpus luteum, all you get are the dregs of progesterone that are kind of incidental, because progesterone is a step in the production of glucocorticoids (like cortisol), estrogens, and androgens (like testosterone).

How to use this explainer towards menstrual domination

I tried to contain myself with this explainer – menstrualsplainer? – to give a basic outline of the process, but ask for clarification in the comments! I am a nerd, I like to expand on things, especially if it gives me an excuse to go read some more of the scientific literature.

Here’s what I want you to take away from this newsletter: the menstrual cycle is worth understanding in terms of its functions. The actual hormone concentrations of a given person are rarely known because the only way to know a person’s full profile is to measure them every single day. And what often matters more than your actual numbers much of the time (though of course it’s important to discuss exceptions, and I will) is what is actually happening – your symptoms, your experiences, your fertility, depending on what you want (or don’t want!) out of your cycle.

For this reason, maybe don’t trust folks claiming they can (or should) “balance your hormones” unless they are medical doctors expressly prescribing hormones.

Add a comment: