The Contemporary Archive

Felt Notes

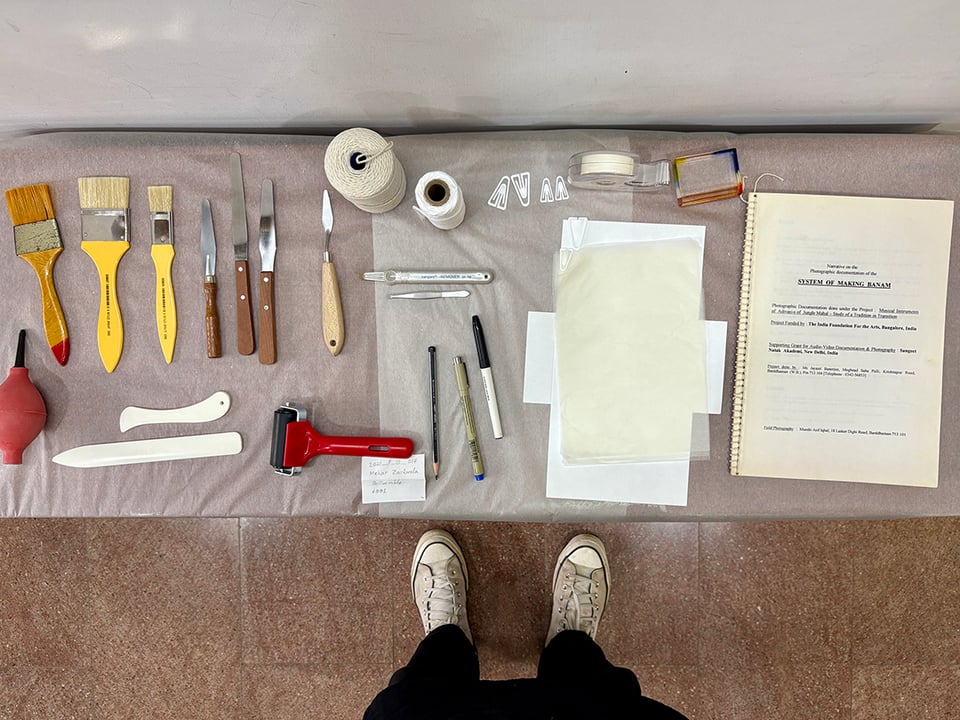

ID: On display are a set of archival tools and implements with which we began our daylong engagements at the IFA Archive on September 25th. As a classroom community, students and I have also added these tools and their references to the seminar installation with the goal to underscore and make visible distinct archival labour. Image courtesy of Kush Patel (September 2025).

This letter comes on the last day of September whilst I’m away on a much needed midterm break—and what better way to mark this moment than with an introduction to my ongoing MA seminar on “The Contemporary Archive” [1]. I’ve structured this unit around the following quoted matter, corresponding to a set of weekly themes each on archived lives; mediating the archive; and archiving as care work:

Let us stop thinking of photographs as nouns, and start treating them as verbs, transitive verbs. They do things. We need to ask not only what they are of, and what they are about, but also what they were created to do. And when they are preserved or digitized, published, or in other ways repurposed and recirculated, we must ask how their material nature has been altered, and in the process, how the relationships embedded in them have changed, why, and to what end. Archival lessons from these alternative narratives teach that we must . . . expand the range of questions we ask, so that we may better understand and account for the movement of photographs and changes in their meaning across temporal and spatial, discursive and institutional boundaries.

— Joan M. Schwartz, “The Archival Garden: Photographic Plantings, Interpretive Choices, and Alternative Narratives” quoted in Michele Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence, Memory, and the Photographic Record in Cambodia (University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 3.

Shrujana describes the archive as “a way to define Dalit artistic and cultural legacies”. Shridhar’s efforts in documenting this aesthetic are an important contribution to a weakly documented topic, and her interpretation of the objects pushes the definition of what an archive can be.

— Tanya George, “Archiving Resistance,” Fontstand News (October 21, 2021).

For [archival] science, its choices of projects, methods, and practitioners, its standards of acceptance, and reasons for exclusion and failure all [reflect] needs and interests, and deeper social, linguistic, ideological, gender, and emotional patterns and power struggles . . . Like scientists, archivists are thus (and always have been) very much a part of the historical process in which they find themselves. Archivists should accept rather than deny their own historicity, that is, their own participation in the historical process.

— Terry Cook, “Electronic Records, Paper Minds: The revolution in information management and archives in the post-custodial and post-modernist era,” Archives & Social Studies: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Vol. 1, no. 0 (March 2007), 319.

Specifically, to honor the connection between archival theory, creative practices, and archival form in the “post-custodial era,” [2] I opened the seminar with propositionings respectively by an archivist-academic, activist-artist, and archivist-scholar. Together, these selections invited us into a conversation about how we may understand archiving not just in the context of our hyphenated-professional selves, but also in the entwining of selves, community histories, and practices of classification and cataloging. What is the resulting archival form and record? How is that record produced? What does the record do in the world? And how does our use of archival records (or the questions of history and memory we ask) inflect the very definition of archives?

Bringing together students of MA Contemporary Art Practice and MA Visual Communication, the three-week-long intensive enables us to examine these questions from a set of personal, community, and institutional locations to unpack—and make specific claims to—the notion of “the contemporary archive.” Here, I use the term “contemporary” not in relation to a given clock time or period—conventionally, the present—but as an affinity to preserve memory and keep alive historical perspectives across urgent temporalities. Engaging with core debates in archival studies, art history, feminist studies, queer studies, transgender studies, and digital humanities, the seminar also includes guest visits to the classroom as well as visits involving local archives in the city to help mobilize distinct vocabularies.

I’m doubly excited about the final project, which is an installation that we are collectively building at these scholarly intersections to address the question of “the contemporary archive” in terms both intimate and intimately contested. Hopefully, I’ll be able to write some more about this installation in a future letter—stay tuned. For now, I want to extend my earnest gratitude to members of the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) Archives, especially Biswadeep Chakraborty, Pranav Sethuratnam, and Shree Nivethitha R for hosting us last week—and for fostering a mutually meaningful connection to all things critical, archival, and community-centered in the arts. I look forward to having you re-join us on the final day of the seminar next Friday, which is when we will make the installation and our unit lessons public.

Notes

[1] This unit builds upon its inaugural framing from last year and extends the discourse on archives and social justice into specific dimensions of art practices and writing. To learn about my Monsoon 2024 seminar on “Archival Activism,” read this letter by the same title.

[2] Terry Cook, “The Concept of the Archival Fonds in the Post-Custodial Era: Theory, Problems and Solutions,” Archivaria 35 (February 1992), 24-37.

About

Felt Notes are monthly dispatches about the work of the Just Futures Co-lab, and the co-labouring worlds of research and teaching in art, design, and the digital humanities that it scaffolds, furthers, and amplifies. The letter writing translates the ever so negotiated nature of this space at Srishti Manipal Institute and the discourse and scholarship on equity and justice I produce with students and wider academic and non-academic community members through critical pedagogy; archival and database constructions; interactive digital storytelling; and inquiries into queer- and trans-feminist digital technologies and knowledge infrastructures.

I hope reading this letter and its upcoming segments are a meaningful experience for you. If you aren’t subscribed yet, you may do so here. If you are already subscribed, I would love for you to share the link with friends and trusted networks as we make sense of our relationships to technology as well as our relationships to each other via technology. If you would like to write or co-write a letter in the future or share any announcements, please feel free to get in touch with me, and whilst you’re here, please also check out the Felt Notes Archive.

Kush Patel