Nonconformity

Felt Notes

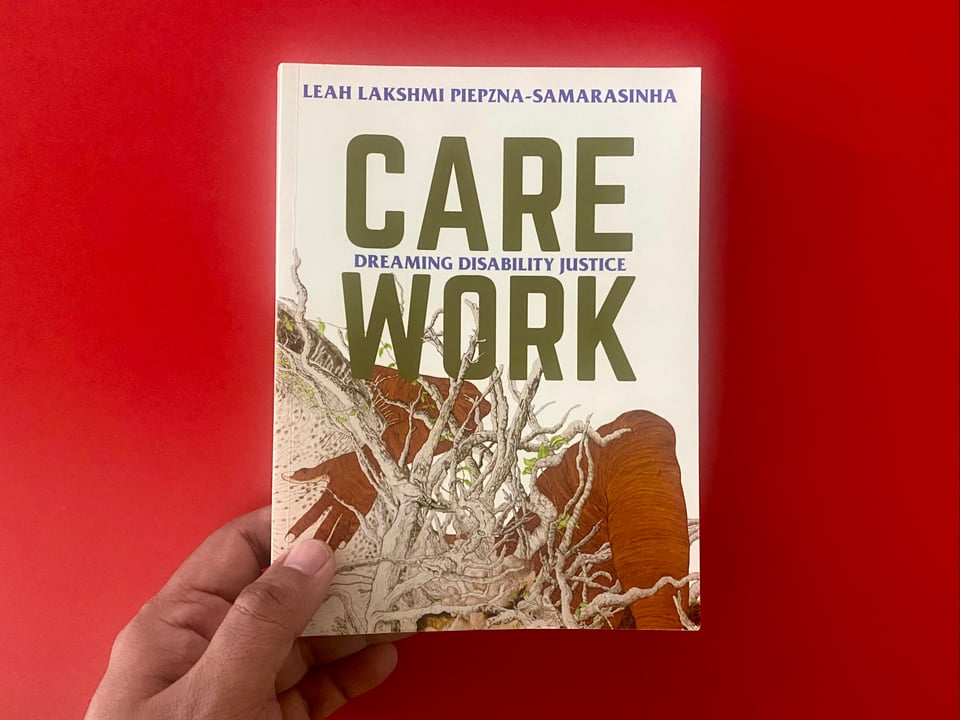

ID: Holding a copy of Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (2018) by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha in my hands; a precious copy that has traveled with me across my digital humanities research and teaching career in India and transnationally. I had opened my very first studio course at Srishti Manipal with this text; a 2021 MA studio that invited students to produce care work biographies of their interactions with technology during, but not exclusive to, the then raging COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the ways in which I brought this semester’s graduate students together in conversation about who we are and how we may come to inhabit the lab was to have them also think and reflect with me on what might constitute a neurodivergent information sheet for accessible and inclusive learning. The resulting version 1 of Neurodiverse Learning Information Sheet (shareable Google document) aims to do just that: to move away from the language and framing of disability accommodations towards centering and honoring their corresponding acts of nonconformity. Please read this document alongside, and in relation with, the other on Gender Identity, Pronoun, and Preferred Name Information Sheet (March 2024).

Disability becomes an identity—a standpoint for resisting normalizing and amplifying nonconformity.—Joshua Halstead [1]

Neurodiversity as a concept and as a movement comes out of early online autistic communities; in the 1990s, the internet was becoming available to the average consumer, you saw the emergence of message boards, chat rooms, and listservs, which in itself was a kind of a new way of forming community across much wider distances than had previously been possible.—Sarah Silverman [2]

What are my learning needs? What are your learning needs? I often begin my course introductions with these questions as a way to center an affirming learning environment for and with each of the classroom and lab members, as well as to make my syllabi accessible to multiple learning styles and comprehension abilities. These introductions are part of the activity on writing space and community guidelines where we establish a set of values and protocols that respect the subject matter under study as well as allow for each individual to challenge received assumptions about the world and about each other’s bodies; to practice embodied and experiential knowledge; and to “grow in our understanding of each other, and the course or lab matter under study” [3].

An accessibility-centered approach to teaching also invites me to explain concepts in our shared syllabus document; a form of immersion to facilitate individual and group annotations, edits, additions, and collective ownership of “the syllabus.” As a pragmatic move, I avoid using stylized fonts and graphics so that the document can be read across screen readers and I ensure any images I use always carry an image description and an alternative text (the distinctions of which I encourage us all to notice and practice) [4].

But how might we center accessibility beyond a simple checklist of tactics in the classroom, or what is consumed as byte-size factoids on social media more generally; factoids that may give individuals the language to converse, but, perhaps, and not readily, a vocabulary and framework to think with, to historicize what we have come to accept as norms, including a normative body, mind, and the body-mind binary? How might we center disability and disability-justice frameworks to structure our pedagogies around accessibility? What shifts when students and learners at large are invited to participate in this inquiry-based work all throughout their conceptual and material engagements in the lab, on campus, and beyond? In short, where might we begin to “amplify nonconformity” as praxis? [5]

Let us begin by acknowledging the needs and specificities of bodies occupying a learning space—and by making adjustments, let us move through that space to honor learning with and across difference in ongoing ways.

Let us begin by historicizing our learning and subject matter to bring to attention the longer histories and genealogies of thought, practice, and pedagogy that may be otherwise rooted in, might circle us back to, and/or inadvertently keep alive the paradigms of conformity in art and design, or what Joshua Halstead has brilliantly described as histories of “norm” pertaining to the body across their “medical,” “social,” and “identity paradigms” [6].

Let us begin by citing, listening to, and actively thinking with disabled scholars and disabled creative practitioners who have been building neuro-nonconforming worlds in all of their bodily-situated and community-centered brilliance; I want to begin by giving a shout-out to Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (on “Carewebs” 2018); Joshua Halstead (on “After Universal Design” 2023); Sarah Silverman (on “Neurodiversity for Educators” 2023), Remi Yergeau (on “Criptastic Hacking” 2014); Petra Kuppers (on “Crip Drifting” 2022); and Aimi Hamraie (on “Critical Design Lab” 2014).

Let us begin by inviting students into this theorization process. Consider, for example, the conversation involving members of this semester’s transdisciplinary research where we read Halstead’s writing, re-visited one of the recent graduates Gayatri Shanbhag’s postgraduate thesis on “Sew Many Ways to Unmake” (2022) [7], and discussed jointly: a) how standardization is closely tied with power, or how standardization creates a map of who is at the center and who is at the periphery. Power also distributes itself in similar ways and the question then becomes who is responsible for the redistribution of this power and in what ways might they do so; and b) How might we come to acknowledge a range of brain functions and behavioral traits regarded as part of a regular variation in human populations, but in non-pathologized ways—and work on the fact that we’re all part of this reality, period, whilst also working against the concept of normality?

Let us begin by expanding the social etymology of the term “neurodiversity” itself. As Sarah Silverman explains the term neuro-diversity has “roots in the early autistic community and the practice of autistic self-advocacy,” which have together helped us move the conversation about neurodiverse learning needs away from their reductionist and pathological bracketing by the medical establishment [8].

Let us begin by building upon threads of previous work coming out of the Just Futures Co-lab, in particular, the Interlude 2022 project on scaffolds for inhabiting learning entitled, “The Office of Anti-Inequity and Anti-Exclusive Excellence: Zine and Archival Metadata,” [9] where one of the project participants and faculty colleagues, Akshay Prakash, asked: “How do we understand disability in the context of higher education? Can private post-secondary institutions play a more proactive role in admitting and supporting students with disabilities, even though they are not not legally mandated by the law? How would an institution (public or private) go about providing [“]differently abled[“] students: a) institutional scaffolding and curricular support for continued education; and b) an infrastructure that would make the physical space of the university more accessible?”

And as we begin, retrace, and further this work in community, let us also remember to view the information sheet as one of creating new possibilities—situated and material—for teaching, learning, and caring; this sheet is not a solution for or a marker of what is commonly understood as disability accommodations.

Notes

[1] Josh A. Halstead, “Disability Theory,” Extra Bold: A feminist inclusive anti-racist nonbinary field guide for graphic designers by Ellen Lupton, Farah Kafei, Jennifer Tobias, Josh Halstead, Kaleena Sales, Leslie Xia, and Valentina Vergara (Princeton Architectural Press, 2021), 40.

[2] Sarah Silverman, “Intro to Neurodiversity for Educators,” Teaching in HigherEd Podcast Episode with Bonni Stachowiak (September 20, 2023), https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/intro-to-neurodiversity-for-educators/#transcriptcontainer

[3] See the opening to “Gender Identity, Pronoun, and Preferred Name Information Sheet” (March 2024), 1.

[4] See: “Write Helpful Alt Text to Describe Images,” Digital Accessibility (Harvard University Blog), https://accessibility.huit.harvard.edu/describe-content-images, Accessed November 3, 2024; and “Write Helpful Image Description,” Access Guide,

https://www.accessguide.io/guide/image-descriptions Accessed November 3, 2024).

[5] Josh A. Halstead, “Disability Theory,” Extra Bold: A feminist inclusive anti-racist nonbinary field guide for graphic designers (Princeton Architectural Press, 2021), 36–41.

[6] —.Halstead (2021).

[7] Gayatri Shanbhag, “Sew Many Ways to (Un)Make: Subverting the Gender Binary in Makerspace Apparel Design Pedagogy,” PG MDes Capstone Project [Unpublished], Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design, and Technology, MAHE, Bengaluru, May 2023.

[8] Sarah Silverman, “Intro to Neurodiversity for Educators,” Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast Episode 484 (with Bonni Stachowiak) (September 20, 2023), https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/intro-to-neurodiversity-for-educators/

[9] Members of the Scaffolds Thematic Group, “The Office of Anti-Inequity and Anti-Exclusive Excellence: Zine and Metadata,” Inhabiting Learning: Under Construction (Bengaluru: Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design, and Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, March 25, 2022).

Thank you for reading and for integrating these questions into your pedagogy. Please feel free to adapt and extend this information sheet (downloadable link) for and into your classroom inclusion policies, and if you do so, please attribute as follows:

This document was developed by Kush Patel (they/them) for the Just Futures Co-lab at Srishti Manipal Institute with feedback from students aṇu, Eyeshaan, Krishnapriya (she/her), Namitha Moses (she/her), Ruhani Chatterjee (she/they), and Shinjini Asthana (she/her) on November 7, 2024. This information is subject to additions and edits in community.

About

Felt Notes are monthly dispatches about the work of the Just Futures Co-lab, and the co-labouring worlds of research and teaching in art, design, and the digital humanities that it scaffolds, furthers, and amplifies. The letter writing translates the ever so negotiated nature of this space at Srishti Manipal Institute and the discourse and scholarship on equity and justice I produce with students and wider academic and non-academic community members through critical pedagogy; archival and database constructions; interactive digital storytelling; and inquiries into queer-feminist media technologies and infrastructures.

I hope reading this letter and its upcoming segments are a meaningful experience for you. If you aren’t subscribed yet, you may do so here. If you are already subscribed, I would love for you to share the link with friends and trusted networks as we make sense of our relationships to technology as well as our relationships to each other via technology. If you would like to write or co-write a letter in the future or share any announcements, please feel free to get in touch with me, and whilst you’re here, please also check out the Felt Notes Archive.

Kush Patel