Lab Life

Felt Notes

May 2024 marked the end of one full academic year for Felt Notes, which means our lab life saw three brilliant graduating works grow from within the pedagogy and research areas of the Just Futures Co-lab and make tremendous contributions to them as well. To Ananya, Navya, and Sowmya: thank you for aligning your inquiries with the lab’s project spaces and for enriching those worlds with your questions, subjectivities, creativity, and reflections. With your consent, I have included below individual final project abstracts as well as your reflective notes on what this lab has meant to each of you both personally and professionally. I hope the letter readers are able to find in these articulations an explicitly feminist voice, which cares for socially and technologically just futures.

Further, as part of the 2024 graduate show and public events last month, I co-led a workshop with Ammel Sharon (Project Director, Queer Archive for Memory, Reflection and Activism, NLSIU, Bengaluru) entitled, “Queer Lives, Queer Archives.” For this session, we pre-selected a set of objects each from the QAMRA Project and Just Futures Co-lab to invite participants into a discussion about the ethics and politics of archiving queer lives, as well as making those records public. In dialogue with the participants’ individual selections, Ammel and I located the objects in context and explained how they connect to the study or making of an archive in analog or digital forms. By the end of the hour and a half long event, it was great to hear the participants’ draw out an understanding of queer archives based on these activities (see the workshop reflections below).

The idea of an archive being more than just a repository of records or an institutional place while being perpetually sensitive to issues of consent as both layered and complex is one way in which I would describe a queer archive. And the very questioning of assigned identities, subverting of expectations, offering representation, finding a safe space and potential for community, and giving queer stories and voices a platform are some of the ways, I feel, that make an archive queer — Reflection 1

The Karnataka Prohibition of Beggary Act of 1975 describing “public manifestations of sexuality” in the context of people being uncomfortable with Hijras on the road and considering them as “disruptive” and “divergent” to “normative” sexuality has stayed with me. Documenting the temporary qualities of queer and trans lives, archiving documents, and organizing the catalog as a place to remember are also some of the things I’ve noted from this workshop. We have to remember how we disappear but this remembering has to be more than a visualization — Reflection 2

The care work being put into archiving by the emotion it evokes in the hands of someone who seeks comfort. The community care needed to fuel and keep alive this protest by celebration and nostalgia. These are my workshop notes — Reflection 3

My thanks again to Ammel for this wonderful collaboration and for her deeply affirming words about the lab or what she saw as the lab doing for faculty members and students alike on campus.

For me, one of the other highlights of the recently concluded graduate show and academic year was the keynote address by Jayna Kothari (Senior Counsel, Supreme Court of India and Co-founder, Center for Law and Policy Research, Bengaluru). Speaking to the Class of 2024, Jayna advocated brilliantly in her capacity both as a practitioner of the law and an activist for why social justice matters in the world—and why it should also matter to the community of art and design graduates, faculty members, and staff of Srishti Manipal. Citing her work with queer and trans communities on the ground and drawing from her sustained research and practice in areas including constitutional law, gender and sexuality law, disability rights, and discrimination law, Jayna argued for viewing social justice not as a choice, but rather as “our constitutional duty”—now and always! When she visited the Just Futures Co-lab after the keynote, I shared the work and agenda of the lab with her and was delighted to hear her respond with such care and encouragement about what this space may continue to offer to communities on campus and beyond.

Last month, I was invited by Julia Wintner (Eastern Connecticut State University Professor, Artist, Curator, and Director of ECSU’s Art Gallery, USA) to display the Co-lab or a small component of it in response to her curatorial framing and exhibition at 1ShanthiRoad entitled “Prophets, Visionaries and Disciples: Srishti Faculty and Students.” The exhibition, which ran from May 3 to May 12, featured SMI individuals, per Julia’s curatorial note, “whose work represents an on-going confluence of artistic research and practice [and] whether prophets, visionaries or disciples, they offer us a profound insight into their recent conceptual and formal investigations.” I’ve included below my exhibition label and note to offer a glimpse into this event and the lab’s presence in the city.

Kush Patel, with quoted matter from Kim Munro

Felt Notes, August 2023-April 2024, Poster

Akshay Prakash, Athena David, Gayatri Shanbhag, Hamna, Kush Patel, Neeraja D, Nithya Kirti M, Santhosh Jayakumar (Srishti Manipal Institute); Aishwarya Das (Shiv Nadar University); Chinmay Gheware and Tanvi Karia (CEPT University); Rupali Gupte (School of Environment and Architecture)

The Office of Anti-Inequity and Anti-Exclusive Excellence, March 2022, Zine

The poster and zine are artifacts from the Just Futures Co-lab, modeling a form of care work that is labour-intensive, joyful, deeply embodied, and even essential for scaffolding the discourse on equity and justice that I produce and co-produce with students and non/academic community partners through critical pedagogy; work on archives and databases; interactive digital storytelling; and inquiries into queer-feminist media technologies. The work of sustaining this lab is also challenging, considering the long history of gendered workload inequities in institutional spaces, involving those of us who are precarious and living outside the system’s cis-heteronormative defaults. Felt Notes are such deliberate entwinings.

And now to a quick announcement: I’ll resume the writing of Felt Notes in August with the start of the new academic year and some exciting news about the lab’s next moves programmatically. As discussed at the beginning, however, I have included the graduating abstracts and reflections of Ananya, Navya, and Sowmya in the section below. Please continue reading this letter, take good care of yourselves, and have a restful break!

Ananya Vepa (he/him)_Postgraduate Diploma Program in Contemporary Art Practice

Embodied Making: Transness and Neurodivergence

Who has wielded sensitivity to resist dominant power structures that seek to control them? How did they do it? Many months ago, a friend and I came across touch-me-nots on the road outside our campus. We knew it was a touch-me-not (Mimosa pudica) because it shrank away from our touch. We knew it to be highly sensitive (a gust of wind could make its leaves fold in on itself), and we knew what it wanted us to do in its name itself: touch-me-not. Yet we touched it to confirm that we knew what it was, and it curled inwards and away from us.

This act was not an incident which seemed memorable to me, until this moment, when I have come to the end or a current ending of working on this keyword entry for the Co-lab’s project space of Queer Futurities. I now realize that my understanding of sensitivity used to be as small as the image of the touch-me-not folding two leaves at a time, but now and based on the work of the last seven weeks at the lab, I have learned to think about my own particular sensitivities as having larger implications than just disruption in my own body. I am still ruminating on this question of self and the larger social self that Kush led me to ask; a question in some ways still rooted in my own individual hangups and insecurities, or what value does my sensitivity have to the world? But in other ways, the scope of my thinking has broadened with the lab: How does my sensitivity compel me, teach me, and help me choose how to act, against the structures that deemed my sensitivity invaluable in the first place?

To help locate myself dialogically, and based on my independent study with Kush, I have dived into the works of two scholars, thinkers, and teachers who have shook me to my core and helped me move from my first question to my second question: Sara Ahmed on on feministkilljoys research blog (2015-Present) and M. Remi Yergeau on Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness (2018).

Reflection

I first heard the term “embodiment” at the Just Futures Co Lab, led and stewarded by Dr. Kush Patel. In the introduction to the Lab, Kush spoke about “embodied research” as integral to the work of the lab, or in their words to the lab’s orientations and approaches, “…the Co-lab will center inquiries and connections that respond to and remain rooted in participatory learning, equitable labor, mutual accountability, and embodied research across its project spaces.”

This “embodiment” both confused and excited me. Hearing it felt like I had a metal detector that had detected something big and important under the sand, but I couldn’t see it or understand it yet. I just had to keep digging and feeling out its contours and work around it to gain an understanding of what it meant to embody something.

Embodiment suggested being moved within your body to study something, to be guided intrinsically to what needed attention. This is how I’ve been drawn to my research interests before, but what the Co-lab has taught me is that embodiment is not only rooted in the body and what you feel strongly about, it is rooted in practice. It is rooted in putting your politics in action. It is rooted in being moved to create, act, and resist. The bodymind—non dualistic, sensitive, embodied—can guide us to resist oppressive structures, to collectivize, and to make.

The Just Futures Co-Lab created a space to learn at my own pace, and to safely explore concepts that required an evolution in how I conceived myself and the world around me. I am deeply grateful for the generosity, openness, and access that Kush’s advising and the Lab community holds for all who come there, and for the lab’s approach to research and pedagogy that has taught me to aspire beyond my essential facts and towards meaningful social action. — Ananya

Navya S (she/her)_Postgraduate Program in Human-Centered Design

Approaching the Question of Safety against Technology-facilitated Gender Based Violence on College Campuses Toward Drafting Collective Community Declarations

College campuses are a place for students to discover themselves and learn. They are environments where students shape their identities. However, with the increased use of and reliance on technology, including online and social media technology in campus life, the cases of Technology Facilitated Gender Based Violence (TFGBV) have also increased in the last decade, leading to low self-esteem and extreme cases of self-harm and death. Additionally, social media algorithms amplify racial and gendered oppressions, arising from data that these systems are trained on. For instance, platform algorithms push sexist and misogynistic content because it gets more visibility than the everyday thoughts, musings, and perspectives of women, including transwomen, and non-binary persons. TFGBV gets particularly amplified from a given social media’s feedback system of comments and post likes.

Technology facilitated gender based violence can take various forms from doxxing, stalking, fraping, morphing, sock puppet, flaming, and more. Fostering a safer online environment becomes crucial where students’ space is respected and their views are heard not only on campus, but also their digital and online extensions into the world. Often, however, when there are support groups in colleges, they feel like a distant entity, placing the burden on students to lead the conversation. When students do reach out, there is a stigma attached to accessing support. Adding to these predicaments and challenges are issues of conscious and unconscious bias that we and the institutions we inhabit travel with, as well as concerns of privacy within and connected to institutional support services and spaces.

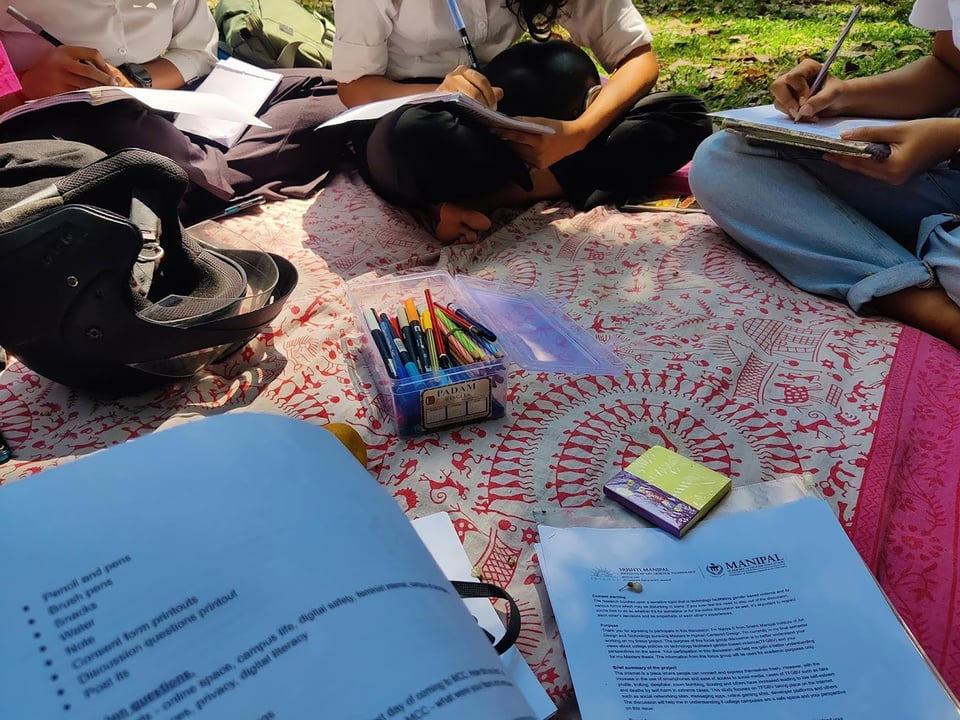

My postgraduate capstone project focused on understanding if college campuses are indeed safe spaces. My inquiry involved unpacking current college policies on online gender based violence; examining provisions at the intersection of law and technology; and studying digital media platform policies. Further, during the course of the semester, I analyzed policies of twenty-five top colleges in India from various disciplines; studied their reporting mechanisms; and looked at current legal scenarios such as the Information Technology (IT) Act, 2000; IT (Amendment) Act, 2008; sections of the Indian Penal Code; Prevention of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act; the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023; and anti-bullying and harassment policies and community guidelines of common digital platforms such as Instagram, Whatsapp, X, Meta, Snapchat, and Github.

Through qualitative research strategy involving tactics such as focus group discussions and one-on-one interviews with legal experts from the Alternative Law Forum (ALF) and digital feminist organizations such as ITforChange, my project aimed to draft a collective and an ongoing set of declarations specific to TFGBV so that our actions and interventions become a community practice, which enable us to foreground questions of accountability and extend them into the academic institutions we inhabit, the digital platforms we encounter and experience, and the discourse on feminist internet we wish to build and nurture collaboratively.

Reflection

I spent my first year at Srishti Manipal exploring various domains of research and design—and finding myself. I attended studios related to product design, typography, data visualization, and user experience design. I interned and learned tools such as Figma, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Photoshop, and After Effects among others. I also wanted to be better at coding, so I enrolled into open web-based courses, practiced coding for a few months, and hosted my projects on GitHub. By the end of the year, I felt that I could be good at all of them with consistent efforts, but I couldn’t focus on building an inquiry because I wanted to learn new tools and do everything all at once. Being enrolled in a masters program, I felt I would graduate without building proficiency at anything in particular.

It was at this moment that I enrolled into the MA studio led by Dr. Kush Patel called “Care Matters and Justice Dreams” as part of their ongoing iteration and interpretation of the course on The Measure of All Things: Quantifying the Human. The studio changed my perspective on art, technology, and society. Positioned at the “intersection of personal data, digital technologies, and the becoming of a human subject connected to workplace surveillance,” we explored everyday digital technologies, unpacked them through a feminist lens, understood the relationship between law and technology implicating data and gendered divisions of labor—and learned how to weave. Yes, weaving as coding and storytelling! By the end of the five-week cycle, I knew I wanted to situate the next steps of my postgraduate learning within the Just Futures Co-lab.

Before the MA studio, my view of digital technology was instrumentalist and design neutral, but approaching technology from a humanities and an explicitly feminist lens helped me understand its ethical and political implications, as well as the impact of its encoded and often dominant norms and values on marginalized lives. At the end of the studio we had to produce an analytical textile piece, a woven artifact embodying the complexity of our chosen workplace technology, which allowed me to review the relationship between thinking-making-doing on the one hand and feminism and data tied to remote electronic monitoring softwares on the other hand.

As someone who previously wanted to do a breadth of things all at once, I now wanted to delve into the specificities of a context; sharpen my skills to formulate a research question; and learn from the frameworks and methods of critical digital humanities that the lab was offering. To maintain this connection and criticality, I went ahead and located my culminating Capstone inquiry in the lab with Kush for the next six months. I also got to audit their theory seminar called “The Future as Techno-Utopia, Community, and Technological Self,” which introduced me to an even wider feminist scholarship on digital technological futures.

Throughout the Capstone semester, the lab encouraged me to step out of my comfort zone, build connections with organizations in and around Bengaluru, and take active part in feminist events, workshops and exhibitions in the city. I’m now more intentional about choosing my projects, thinking epistemologically and methodologically, seeking supportive communities in the region for personal and professional growth, and furthering a career path that can feel more aligned with my work goals. As an inquiry-based practice, I am clearer in what the intersection of digital technologies, gender identity, and concerns of privacy can offer to my pursuits moving forward—and by being more systematic and collectivist with my process, I have also been able to deepen my conviction and confidence to act more collaboratively in the world. — Navya

Sowmya C (she/her)_Postgraduate Program in Human-Centered Design

Reading Across Girlhood Tropes: Building Feminist Storytelling Spaces

In this project, I aimed to understand the relationship between social constructions of gender and girl stories, and the implications of this relationship for individual wellbeing in the context of works: fiction, non-fiction, and folklore. I explored narratives, or the practice and politics of telling stories, as a tool and medium of knowledge-making to build spaces that care for the social wellbeing and identity formations of children, particularly girl children. My Capstone inquiry was oriented to building storytelling spaces that are conscious of the role and value of critical curation in society. In this research, I studied how popular narratives and their curation reproduce patriarchal norms and where there might be possibilities for other ways—and more feminist ways—to engage girl readers.

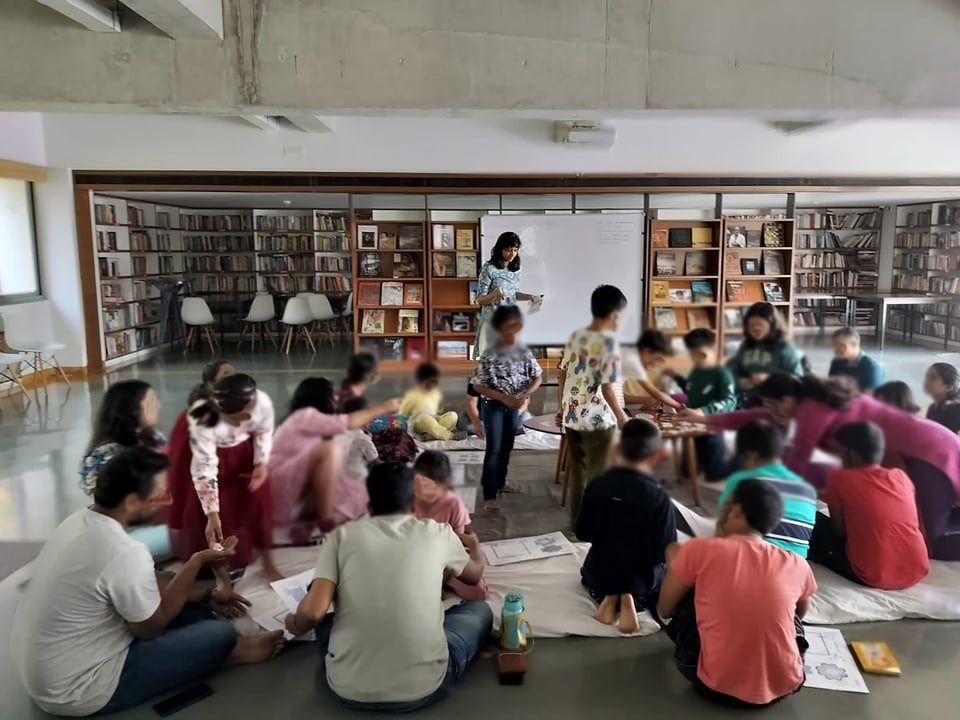

The project was situated across three active storytelling spaces in Bengaluru: 1) a children’s bookstore called Lightroom Bookstore; 2) a privately owned public library, namely, the Bangalore International Center Library; and 3) an independent children’s book publisher, Bookosmia. All three spaces engage with children aged five to nine through curated publications, including folklore, and storytelling sessions and workshops. Through practice-based research, I worked with long-time storytellers such as workshop facilitators, curators of children’s stories, and narrators who directly interface with children in live storytelling sessions to analyze what constitutes critical storytelling in imagining girlhood. I approached criticality in terms of content selections, diversity of curated works, and formats of storytelling across these spaces. I also unpacked how and why a community-centered approach to hosting and facilitating workshop sessions might support critical storytelling.

My ongoing creative and pedagogical intervention involved collaborating with the independent book publisher partner, where I learned and drew from critical pedagogy and feminist girlhood studies, as well as my iterative and participatory engagements in community to develop and deepen my workshop design. The design and development of these workshops through time were also the creative and process-based artifacts of this project. With this inquiry, I plan to continue working with my chosen partners to additionally support their initiatives of bringing storytelling closer to girl children, especially those with limited to no access to curated storytelling spaces.

Reflection

One of my earliest conversations with Dr. Kush Patel was during the orientation week at Srishti Manipal on its then N3 campus. I was curious about design research, about finding my way through graduate school, and about orienting oneself to academia. Since then, my relationship with design research has evolved. A significant amount of this wayfinding was made real at the Just Futures Co-Lab. I was introduced to the Co-Lab’s work first through a theory seminar on the future of human and digital titled, “If Technology Will Not Save You, What Will?” that Kush facilitated in Winter 2023. I continued to train with the lab through its five-week-long MA studio in Monsoon 2023 called “Care Matters and Justice Dreams.” Within the studio, I learned to ask critical questions I did not know I needed to ask about socio-technical digital platforms. I had fun analyzing digital objects and systems, and experiencing making as inquiry-building. We produced woven artifacts, each an analytical piece that made our study of digital technologies palpable; it was an approach that Kush drew out to further critical making in everyday digital humanities. In the culminating Capstone project, I developed a pedagogy-based inquiry that helped me reflect on my practice, engage with relevant organizations, and (quite like the lab) honor relationship building as one of the core values of public scholarship, continuing beyond the length of the 20-week Capstone semester.

Encouragement to work towards equity and justice has been one of the constants of the Co-lab. I have always been able to find a space in the lab to voice my thoughts, to remain contextual, process-based, and participatory in my approach—and I credit Kush for the critical and enabling research and pedagogy that they practice. Overall, the lab has not only been supportive of my explorations with feminist research, but has also given those explorations an unapologetic feminist life and purpose. — Sowmya

About

Felt Notes are monthly dispatches about the work of the Just Futures Co-lab, and the co-labouring worlds of research and teaching in art, design, and the digital humanities that it scaffolds, furthers, and amplifies. The letter writing translates the ever so negotiated nature of this space at Srishti Manipal Institute and the discourse and scholarship on equity and justice I produce with students and wider academic and non-academic community members through critical pedagogy; archives and databases; interactive digital storytelling; and inquiries into queer-feminist media technologies and infrastructures.

I hope reading this letter and its upcoming segments are a meaningful experience for you. If you aren’t subscribed yet, you may do so here. If you are already subscribed, I would love for you to share the link with friends and trusted networks as we make sense of our relationships to technology as well as our relationships to each other via technology. If you would like to write or co-write a letter in the future or share any announcements, please feel free to get in touch with me, and whilst you’re here, please also check out the Felt Notes Archive.

Kush Patel