The Republic

We live in a world of words. That is a cold, hard fact.

The who, the what, the when, the where. The why.

Words define reality. Words create power.

It takes bullets and beatings to defeat words, to quiet voices. Either the meaning of words must be perverted or critics silenced.

The so-called “men of action” are compelled to speak, to be heard.

They babble and lie because it weakens them to act in silence. They need an audience. They need to believe they are understood.

What do we call a tyrant?

A dictator. The only one who speaks. The one whose words become law.

What then is dialogue but democracy itself?

I was lucky to have been taught Plato’s Republic at the right age, which I believe is around fourteen. (Or 13, 15, 16, etc.)

The Republic is a YouTube essay. A comic book. A radio play.

Characters and dialogues.

It’s a pop culture contraption for creating order through persuasion – not force.

Why persuasion? Because power – which is not the same as force – requires subjects to participate in their subjugation. (When that power is legitimate, we submit to the greater good.)

The torture tape that Trump and the scumbag traitor Marco Rubio put out last week, after they kidnapped innocents and sold them into slavery, is full of Hollywood conventions. Why? Because they need to create meaning – they demand that we mistake a lie for the truth.

Still, the truth remains valuable. If obscured.

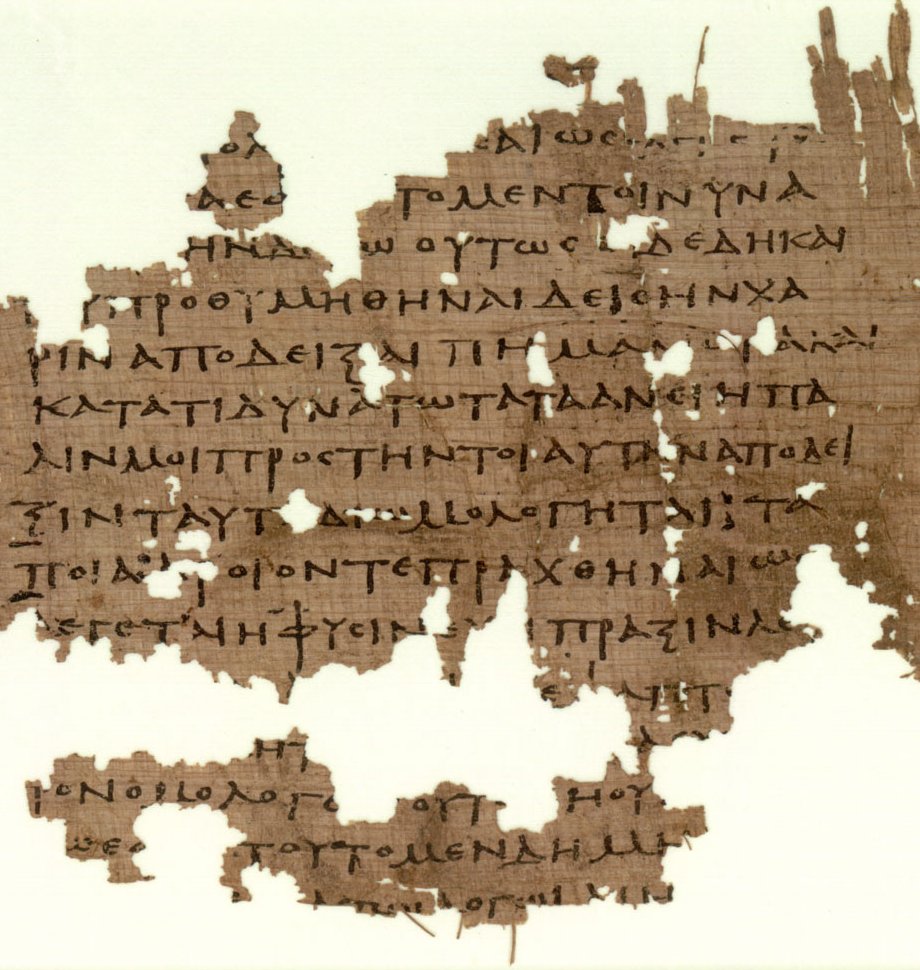

This morning I looked for my copy of the Republic. Apparently, it’s lost. But online, I was able to find the quote that I copied down on its inside cover many decades ago:

he fixes his gaze upon the things of the eternal and unchanging order

As a child of the late 1970s and early 1980s — a refugee, as well — the myth of space exploration was everywhere and intoxicating.

The stars meant freedom.

So when I was introduced to Ancient Greek writers, for whom the stars were of fundamental importance, every reference to star gazing felt like “a sign” that my childhood obsession was meaningful.

The stars are facts that don’t care about our feelings.

Last night at dinner I explained to our boys why I had made them watch this beautiful lecture about the Antikythera Mechanism; a dazzling complex computer made by the Ancient Greeks a thousand plus years before the renaissance.

Except, I didn’t tell them anything.

Instead, I asked them:

“Why did [the lecturer] say they were shocked by the discovery?,” I asked.

“Because people from that long ago aren’t supposed to be that advanced,” our 11 year-old answered.

I then explained that progress is not linear; that sometimes great civilizations collapse and their achievements are lost.

Earlier today, a friend shared with me a dialogue he asked a computer to write for him, in order to continue a conversation with someone who is no longer available to us.

My friend input their correspondence and transcripts into a computer, and then they asked the software to a write a conversation that had never occurred but was always already there – in the interstices.

And in the resulting, artificially generated dialogue, more of the truth was revealed.

Either you believe in the collective unconscious or you don’t. Either you believe that poetry can be suffused with spirit, or you do not.

But if you do, then you must also believe that spirits can leave a trace and that meanings present but indecipherable can be made clear and plain.

Like you, I spend much of my time asking “will the coup succeed?”

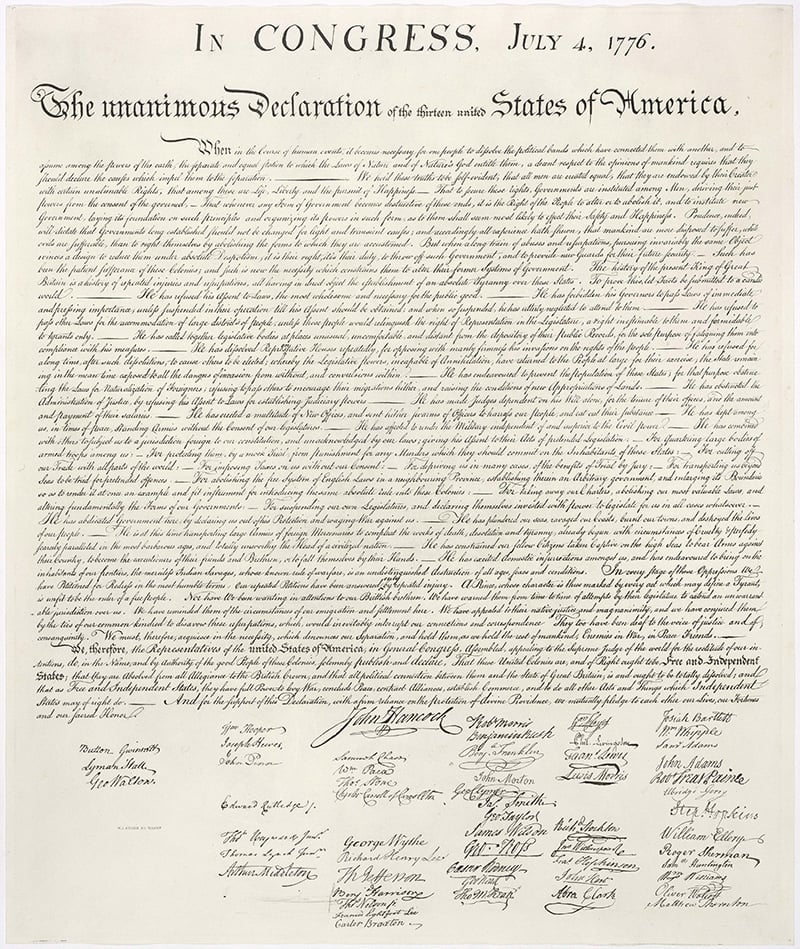

Will the Republicans destroy the Republic as it was constructed, carefully, some 250 years ago? (And then defended some 160 years ago.)

Analogies to the past, and to other countries, only take us so far.

Will the authoritarians who have slowly, carefully, methodically, taken control over at least two branches of the US government resort to the kinds of tactics Erdogan used this week, such as jailing people over their use of electronic media?

Are there other technologies that may prove disruptive?

Probably, yes.