Episode 001 - Purpose

Hi! You're in a newsletter now.

Hey Friendo, you made it! Welcome to the Bubbleup, the newsletter from me, Ben. If you've made it this far, you probably know who I am and what I do, but just to be safe here's the spiel. I'm a cartoonist and game designer local to Boston Massachusetts. I've been a member of the indie comics scene since 2010, and started working in Miniature Wargaming and Roleplaying Game spheres in 2018. I'm also a manager at a FLGS (friendly local gaming store,) and while that keeps me busy, I still do everything else I listed above. I know what I'm about, and now you do too.

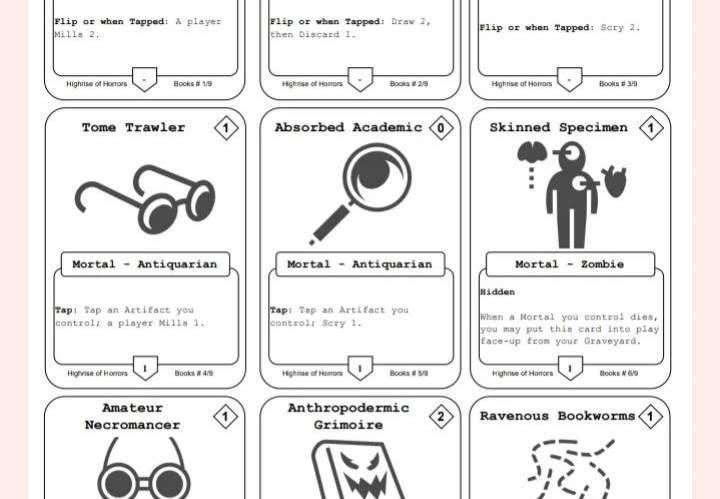

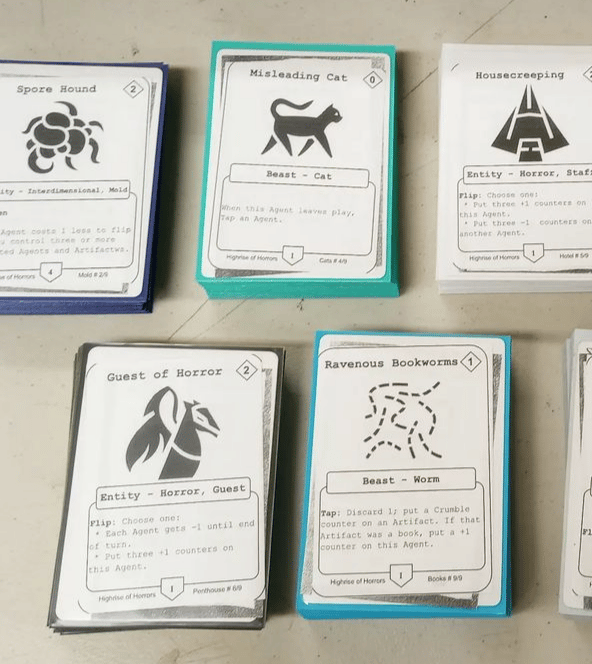

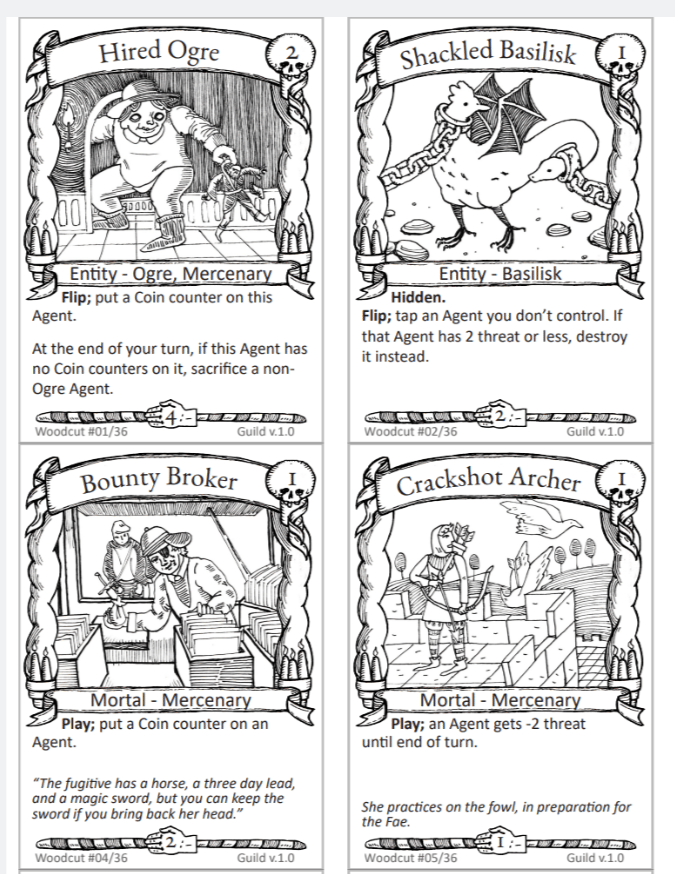

Anyhow, in this inaugural episode of the Bubbleup, I'm happy to announce the launch of my new game, RITUAL XCG with my partner in crime Nicolai Ostergaard. RITUAL is a horror-themed XCG (expandable card game) reminiscent of competitive card games, where players use agents to complete rites, and artifacts to support their strategies, all in service of completing a ritual to doom the world.

While articulating my excitement with this milestone is a challenge, I can easily say that I am overwhelmed and humbled by how positive the response has been to this release. Succinctly, thank you to our communities who believe in us, and maybe even what we're doing. I'm sure that in a vacuum, I would still make things that look like art and games, but being able to share these with you all gives the work a greater purpose. So again, thank you from the bottom of my heart. It means the world.

But on that note, this newsletter isn't simply an announcement or a strategically timed advert. I wanted to take some time to talk about Purpose. Why did I make a game? Don't people have game at home? Since so many games exist, aren't we just reinventing the wheel at this point? Why waste time on doing things that have already been done?

Thank you Mr. Strawman, I'm so glad you asked.

In an alternate timeline I could have been a biology teacher. The science teachers at my high school were all phenomenal human beings, and had I not been so enamored in the arts and humanities, I might have let the siren's call of organizing data and procedures pull me in a very different life direction. However, one of the important things I remember from my time in chemistry and biology, where we were given just enough chemicals or specimens to learn about a reaction or a structure, or a process. These weren't open-ended experiments, as clearly the frontier of frog dissection wasn't being pushed in a high school science class, but they were fundamental as we fledgling scientists were reckoning with our internalization of concepts and our abilities to apply them in hands-on circumstances. Millions of students had done the projects we were doing, but because we learn by doing and by listening, it was valuable for us to get those lower stakes and higher access experiences so that we could reach this greater understanding.

The same applies to games. What does it cost me to learn about the ways that people make, play, and produce games? It takes time, where I can study the lessons of the designers who came before me. One of my favorite resources (and likely the reason this newsletter is so long) is Mark Rosewater's Drive to Work podcast, where he talks about the lessons he's learned both firsthand and from the designers that came before him. How else do I learn? How else to I experiment? I get experiential learning by making a thing and setting goals for how I want it to work, trying to use the thing, and then reflecting on how that thing did or did not meet the expectations I set. Maybe I do this alone to save time, or with friends to see if they interpret the experiment or the results the same way that I do, but I follow my procedure and iterate often to hone in on the goals I'm looking to achieve. It is possible that my experiment looks like experiments that others have done in the past, but we have new tools or different goals, neither of which those earlier designers had access to or awareness of.

An example would be this; I really like trick taking games, which is a family of games where a leading player plays a card, and that card determines what cards other players can or should play during a round. Many of them use a classic deck of cards, because at time of invention, that was the technology those designers had available. Whist is a family of trick taking games where you want your team to win as many rounds as you can, and is fairly straightforward as trick taking games go. However about a hundred years later in a Spanish parlor room, a variant of the game was born, where winning tricks with certain cards in them incurred a penalty, and changed how players strategized entirely. Hearts innovated on the theme by adding meaning to cards outside of their numerical value, just as other games changed the size of the deck, or added new components or rules to advance the genre. Each branching iteration creates a new opportunity to use tools, concepts, and language players already have, while giving them fresh and fun experiences.

Now that doesn't really answer the question of "why make a game?" We've established that with greater access to tools and knowledge, and with the ability to contextualize and iterate, future games can come into being, but we haven't found any reason for such skills and information to be put to use. In this case, the concept of Ritual congealed about two years ago, when my friend John and I were discussing dead CCGs (Collectable Card Games,) and what they had in common apart from being defunct. In this conversation, we decided that convoluted rules and reliance on extrapolation were some of the more frequent offenses of these games, making them impenetrable to newcomers and tainting general perception. Originally, Ritual was going to be a loveletter to all of these overcomplicated mechanics and badly executed ideas from bygone days, but then it occured to me that those mistakes of yesteryear were still with us, just in different clothing.

As I mentioned earlier, I work in a FLGS, and as part of my job I need to be able to teach people games. Though I am not a competitive person, I have a passion for the design and strategy of games like Warhammer and Magic the Gathering, which has led to a lifetime of exposure, and that has lent me an edge on most folk when it comes to understanding how games work. Being within these games' ecosystems for so long means that I've been able to learn the tools, concepts, and language as they change over time.

Games like these are alive in a sense, as their designers make new verisons of them through expansions or editions, and oftentimes building on technology or lessons learned from previous iterations, shifting the emphasis of their elements to engage their communities, add variety, and enrich play. This makes a terrific puzzle for their infranchised audience, who have the context to infer implications and extrapolate information as a game becomes richer, or in some cases, more insular. Given that the literacy threshold gets higher and higher with every iteration, potenial beginners are effectively gatekept as the teachable fundamentals of the game get further away from what the game actually is as it's played.

For example, when I was a kid, my grandfather taught me chess. The pieces all had moves that were unique to them, and when they landed on a space occupied by an enemy piece, that enemy was captured and removed from the board. Eventually, you move enough pieces, capture enough enemies, and corner the opposing king, and that's how you win. That's the jist of how to play basic chess. That is not what real chess is though. Chess is planning your next ten turns, considering all the moves your opponent can make, and assessing which of those moves pose too great a threat to the plans you made, and whether or not your opponent has recognized that those are moves they can make. Both of these games are named chess, but at the end of the day, they are not the same.

This issue is compounded in CCGs, because time is only one of the investments beginners make in exploring a new game. No matter what kind of chess you're playing, you only purchase it once because they use the same board and the same pieces. Because the variety of pieces is a feature in these systems, and because the use of those pieces changes based on which version of the game you're playing, new players can end up wasting real resources preparing for the basic version of the game, when everyone else in their ecosystem understands and is playing the real version. This can feel like a betrayal, like showing up to a LARP (live action roleplay) when you thought you were attending a costume party. The expectation doesn't match the reality, and it can be embarrasing, frustrating, and sour your ability to further engage with the experience.

Correcting for the misunderstanding can also be costly in these collectable environments. Because of the model CCGs follow, some cards are scarcer than others, and if those scarce cards are also good, they can become expensive and even predatory. Buying a pack of randomized cards is not so far from gambling, when the hopes are to open expensive or powerful cards with no guarentee of return on investment. This distribution model is specifically designed to be a repeatable purcase, which as we've seen in other microtransaction markets, can become an addictive loop for some. While gambling can be avoided (by letting others gamble,) players then encounter the secondary market, where people who did open valuable cards can then charge others for the service. If players can't engage in either or both of these practices, then they are again kept from playing the real game, as even with the understanding of how game pieces are relevant or important, that knowledge can't be implemented without access to those cards.

In contrast to the collectable games, LCGs or ECG/XCGs (living and expandable cards games) can offer the same kind of customizable and competitive play as the former, but instead of distributing their cards through randomized packs sell their sets as a single package. Usually, this lets their players make one purchase per product in the system to acquire the components one needs for play... unless it doesn't. Despite components being a known quantity, many of the expansions for these games intentionally include some cards in suboptimal distrinbutions so that repeat purchases are necessary for optimized play. This issue sometimes extends to the core game products, which smacks of the bait and switch experiences we examined earlier. If the stated benefits of the genre are immediately proven to be untrue, its not only disappointing, but damaging to the hobby as a whole. If a game demands your time and intelligence and money, but respects none of it, it's no wonder that the genre as a whole is struggling with courting and retaining new players.

At this point we've established that there are a number of problems plaguing the games in the competitive card game genre, and that they hinge on the complexity threshold, the access to game pieces, and the predatory practices of their parent companies that alienate the new and entrap the entrenched. For some these points I've addressed as issues are features, not bugs, and are integral in the enjoyment and sustainability of the game and the places its played. As a FLGS employee, I've had moments where my involvement in the collectable games industry feels complicated in ways that made me deeply uncomfortable, and while not all of my interactions are crisises of conscience, they are the ones that stick with you.

So why make a game? I can't tell you about your motives, but the ways I justify my work is as follows; it gives me a chance to learn and experiment, and it gives me ways to invite people into experiences that they might otherwise not have access to. By making something new, a designer adds their perspective to the conversation that can then have the potential to further the conversation, which in turn helps designers down the road to make even better games. There are no guarentees in life, but working towards hope is infinitely better than the strawman shrug and accepting things for the way they are.

During the height of the pandemic in 2020, I had gotten really into Inq28 (a subgenre of miniature wargaming that focuses on bespoke figures and narrative games,) and I had noticed a pattern on Instagram where people were struggling with being able to afford the hobby, and finding rules that could work in isolation. While thinking about those issues, I found Samuel Allen's Lobsterpot art, depicting folk in English civil war era dress with arthropod appendages, and something clicked. We talked a bit and I asked if I couldn't make a game using his art and worldbuilding as my basis, and when he said yes, well, I made that game following the tenents I thought were important. Lobsterpot had to be able to be played solo, coop, or competitively, in a very small place, with minimal numbers of figures, that could be accessed for free online, and I think in the end I met my goals. It wasn't the perfect game, but it did the job it was designed to do, which was help people when they were down, and it worked as a stepping stone for other, better games to jump out from.

So make a game, because you want to, or because you believe a thing, or because you know things could be different if only someone would make them different. You can be that person. Why not? Who's stopping you. Not me.

------

Thank you for reading my first newsletter. If you're curious, Ritual XCG is available on PNP Arcade and is a game you can read and/or play. If you're curious, but not about Ritual, here's my hippolink, which leads to other places. Good luck, and stay hydrated!