"I Sound Like This": The impossible soundscapes of David Lynch

The following is an expanded/slightly deformalized version of a paper I wrote in my undergrad and subsequently presented at AMS Midwest 2021. Given Lynch’s recent passing (and the relationship with his art I developed over the course of writing this paper), I felt it was worth revisiting. It analyzes the 8th episode of Twin Peaks: The Return, an episode of TV so strikingly abstract that I won’t even bother with a spoiler warning for it. I’ll keep it largely faithful to the original paper, though I may include a few italicized reflections and interjections given the past four years (and past few days…) have had me thinking about this work a lot more.

Introduction:

David Lynch’s career 50-year long career has had a tremendous impact throughout film and television, leaving a substantial mark not only on how we view cinema, but the very way that television is made. Twin Peaks, the landmark series from Lynch and collaborator Mark Frost, created a new standard for the way fiction could be presented on TV, in many ways foreshadowing the modern era of prestige storytelling. While his work is most famous for its use of dream logic, surrealist imagery, and dark theming, an oft under-appreciated element is the sheer attention Lynch gives to sound design and music.

While Lynch is known primarily as a director, he is credited as sound designer on seven out of his ten feature films (as well as all 18 episodes of Twin Peaks: The Return), and has had several longstanding collaborations with composers and musicians (most notably Angelo Badalamenti and Julee Cruise) who he worked with extremely closely. Additionally, almost all of his work features meticulous use of pre-existing music, and as a result his films are just as interesting to listen to as they are to watch. His work contains some of the most fascinating use of sound and music in all of cinema, and as eclectic and unclassifiable as much of his filmography is, this attention to detail results in a number of persistent musical/sonic tropes throughout his work. After much deliberation, I’ve classified the four tropes that appear most persistently throughout his output:

Sound design that blurs the line between the diegetic/non—diegetic.

Diegetic musical performance within the narrative.

Pre-existing music that is used to distort our perception of events within the film — or the music itself may be distorted from our usual perception of it.

Traditionally composed score, which is often diegetically ambiguous.

these are loosely ordered in terms of overall prominence but this of course varies from work to work.

While none of these “sonic tropes” are entirely absent from the work of other art filmmakers, few have gone anywhere near as far as the cogent and detailed sonic canvases as Lynch has. These tropes have been with Lynch from the beginning of his career, first properly showcased in his 1977 debut Eraserhead, and reaching their apotheosis in Lynch and Mark Frost’s 2017 revival of Twin Peaks. The 18-episode series (each episode directed by Lynch) features all of his surrealist and unconventional storytelling approaches, but does something the original 91-92 series could not: Push these tropes of sound design to their absolute limit.1

As a case study of Lynch’s approach to sound and music throughout his career, I will be analyzing 5 sequences from the 8th episode of this revival (henceforth referred to as The Return), showcasing the incredible attention to detail in Lynch’s use of sound and music, and how that detail-oriented approach creates a remarkable degree of structural cogency in an episode that is otherwise almost wholly focused on the abstract.

Part one: (The) Nine-Inch Nails.

Eight episodes into The Return, the audience will surely have grown accustomed to the musical performances at The Roadhouse (the town’s local bar) that accompany the credits of each episode (all examples of trope #2). These performances feature artists and bands performing under their real names within the universe of the show, already creating an unusual blurring between the world of The Return and our own. Prior to episode 8, these performances have served as little more than atmospheric credits accompaniment, so it proved quite a shock to me when five minutes into the episode, we are greeted with an incredibly disturbing performance from the band Nine-Inch Nails, performing their song “She’s Gone Away.”

This song and its placement are notable for several reasons, the most prominent being its hyper-aggressive character (compared to the previous performances at The Roadhouse, which all tended toward the ambient). Repetitive rhythms, overdrive electric guitars, high whistling drones, disturbing lyrics, and a vocal performance from Trent Reznor that blurs the line between screaming and singing, it confronts the audience in a way that forces them to reset their expectations for what could happen moving forward in the episode. After seven episodes of credits performances, Lynch breaking the pattern in such an unprecedented fashion leaves the audience rudderless and unable to predict what might happen.2

It is reasonable to reflect on the song being performed: Why not play the song non-diegetically over top of an independent sequence, as is often the approach most filmmakers opt for when working with music? I believe Lynch is centering the spectacle of performance to prevent the audience from decoupling themselves from the song’s atmosphere and content (which are decidedly unpleasant). In isolating it and letting it play for its full length, we must embrace the darkness “She’s Gone Away” offers us. This is no stranger to Lynch’s filmography, think of Eraserhead’s “In Heaven,” or Mulholland Drive’s Spanish rendition of Roy Orbison’s “Crying.”

Before we move on to the next (in)famous sequence however, it is worth examining the lyrical content of “She’s Gone Away.” Reznor speaks of clawing fingers, infection, the spilling of seed, and the day the unnamed “she” died, and licking her rotting skin in some perverted attempt to feel something. This is to say nothing of the chorus, which simply repeats the title of the song in a dark and repetitive refrain. Given that this episode (for all its abstractions) is centered around Laura Palmer and the dark specter of Killer BOB, Lynch’s choice to use this song is not insignificant — the lyrics seem almost tailor-made for the relation between these two characters, around which the darkest aspects of Twin Peaks (and this episode) orbit. Given that this song was written specifically for The Return and that Lynch requested a song that would “make my hair stand on end,”3 it is understandable how a song this nightmarish would intrude its way into the episode.

Part two: July 16th, 1945 (Atomic Birth).

The blackest of nights. The date appears onscreen. A voice on a distant speaker counts down from 10. Suddenly, there is a blinding flash of light, and with the shrieking strings of Krysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, the world of Twin Peaks is thrown on its head. The extended Atomic Bomb sequence of episode 8 is now infamous: for almost 9 minutes, Lynch assaults the eyes and ears with a nightmarish audiovisual hallucination of the first Trinity Bomb test.

The instant the bomb goes off, Threnody begins, resulting in one of the most fascinating elements of the music in this sequence, that being the way it supersedes the diegesis. Threnody is (for the vast majority of the sequence) the only audio cue we have, and its place in the diegesis is not strictly obvious. Clearly there is no string orchestra playing at the heart of the explosion, but the choice of Threnody as a symbol of horror points to something more here (to say nothing of the way Lynch cuts up and remixes the original work to suit the timings and visuals better).

Reba Wissner notes Threnody’s metatextual significance, a piece that Penderecki deliberately chose to associate with the horrors of the bomb, and this was clearly something Lynch was aware of in choosing it for the sequence4. According to Lynch himself, he originally planned to have the sequence scored by longtime collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, but chose to use Threnody as it felt ready-made (though Lynch did remix the score to better suit the timings of the sequence).

The remixing of Threnody to fit the onscreen action is too detailed to analyze in this paper, so I will instead examine the matter of where it fits within our diegetic spectrum. Robynn Stillwell’s “fantastical gap,” i.e. film music that cannot clearly be said to fit either diegetic or non diegetic, seems to apply here5. While this angle of approach is promising, in Stillwell’s definition the fantastical gap is a transitory space that music “passes through,” which does not fit with Threnody’s constant, overwhelming, and unchanging presence. At no point is the music ever “onscreen,” and yet through Lynch’s careful editing, the shrieks and groans of Penderecki’s strings begin to reflect the bubbling and boiling world of sight and sound within the heart of the bomb. Jeff Smith’s model of analysis, which seeks to examine the diegesis of music through a film’s aural fidelity and narrative communicativeness, can prove helpful in examining a later sequence in this episode, but is perhaps not as useful a mode of analysis for this specific sequence6.

In light of this enigma, I would like to posit a perspective that hopefully reconciles some of the difficulties of this sequence. As we will see in Part 4 (and as Brook McCorkle notes in her excellent article on the topic7), Lynch and his co-sound designer Dean Hurley often draw elements of sound design into Stilwell’s fantastical gap, musicalizing and giving them significance. Here, I believe he has done the reverse, reducing a piece of music into a form of diegetic sound design.

My reasoning is twofold: Firstly, Threnody’s presence in the bomb sequence is absolutely overwhelming (in a 9½ minute sequence, it players for over 7), and how when other sound design elements manifest, they are used almost as “underscore” to Threnody, in some cases interacting with and interrupting it (see the convenience store sequence at 21:21 in the episode for a clearer representation of this). My second line of reasoning relates to the abstract nature of the sequence itself: Amidst the whirls of static, fiery glowing clouds, a demon vomiting pestilence into the world, how much of these are abstract symbols, and how many are meant as literal events? As with many of Lynch’s most iconic sequences, one can make a compelling argument for either reading.

As a result of these abstractions (and the aforementioned edits to the music’s structure), I believe we can read Threnody as having been “sound-designed” into the sequence, just as sound design will be musicalized later in the episode — the experimental nature of this sequence distorts a great deal of the audience’s perception from a narrative, visual, and auditory perspective. Lynch’s sonic canvases are extremely complex, and the narrative/symbolic complexity that accompanies this leaves the matter of diegesis and sonic function very difficult to pin down. The creation of the atomic bomb is at the core of the Twin Peaks mythos, and it is appropriate that its relationship to this bizarre and unexplainable show is portrayed in as bizarre and unexplainable a fashion as possible.

I think this reading holds up. I think of some of Lynch’s short animated projects, or perhaps the ending of Eraserhead. The sound overwhelms in those, in the ending of Eraserhead the world literally grinds itself to a halt, with an overwhelming wash of noise. Is that distorted electroacoustic soundscape truly so different from the nightmare we hear with Threnody? I don’t think so.

Part 3: The White Lodge (Relief and Catharsis)

After the unrelenting nightmare of the atomic bomb sequence, Lynch transports us to a new ethereal world — one that is still unsettling in many ways, but is reassuring compared to the abrasiveness of the prior sequence. We move across a purple sea into a mysterious buffeted fortress, and enter an ornate parlor. A woman sits on a chaise longe, as an echo of jazz loops and distorts from the phonograph player next to here. This track is “Slow 30s Room,” and is credited to Lynch and Dean Hurley.

According to Frank Lehman’s analysis of this sequence8, “Slow 30s Room” is pantriadic, shifting back and forth between tonal centers with almost no attention paid to traditional tonal syntax. Given the dynamic flatness and obscuring of the static, it makes finding our place in the music difficult — it can come from anywhere, and it can go anywhere, directionless harmonies in space. Lehman’s analysis is excellent and detailed, so I will instead be focusing on what comes immediately after “Slow 30s Room.”

We are taken to a darkened theater (that astute Lynch viewers will recognize as Club Silencio from Mulholland Drive), where a giant individual credited as The Fireman watches the events of the bomb sequence on a theater screen. Moments later, he begins to levitate and emanate a golden mist, a shocking image against the black and white we have now spent the majority of the episode in. This is when Angelo Badalamenti’s track “The Fireman” becomes prominent in the soundscape — a surreal and diegetically ambiguous score that could either be a theater organ accompaniment in this mysterious space, or simply some non-diegetic synthesizers.

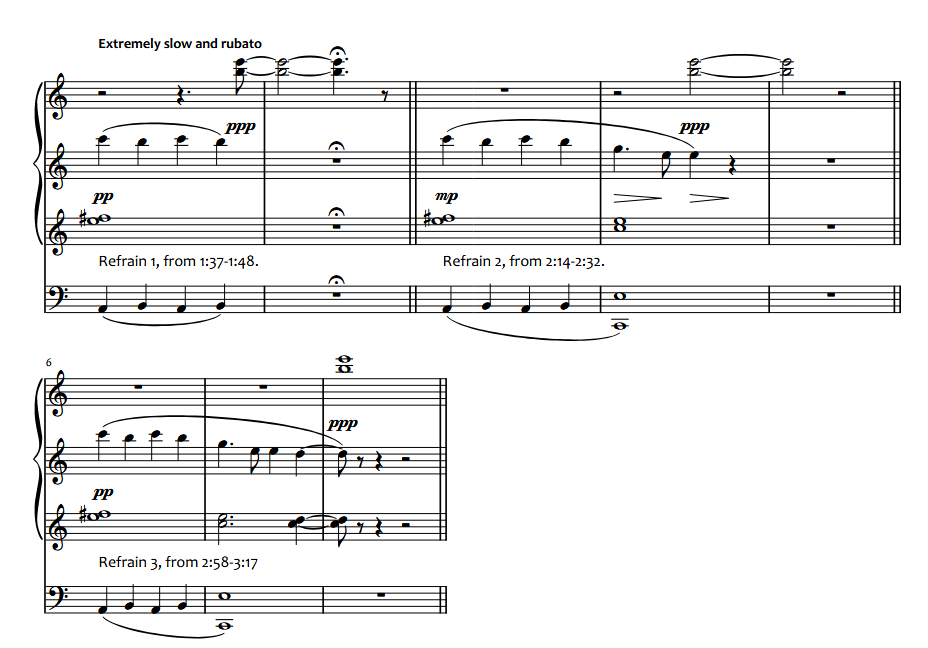

The track is centered around a modal refrain (transcribed below) that expands each time it returns. The uneven interruption/expansion of the refrain creates a unique effect, one that leaves the track in a state of suspended animation, with the glacial tempo and slow alternation of few ideas bringing to mind some of the organ literature of Olivier Messiaen, such as Le Banquet Céleste. Readers will note the high droning tone that repeatedly interrupts the end of the pattern, and this elision between different strands of musical material adds to the disorienting nature of the track — the usage of repetition and distortion of when ideas begin and end make the piece remarkably hard to orient oneself in, creating an incredible sense of stasis (though in a strikingly different harmonic syntax than “Slow 30s Room” moments before).

One of the most striking elements of this track is its function as a sonic opposition to the soundscape of Threnody. Where Threnody is a source of dense/disjunct textures driven by strings and the unsettling onscreen imagery, “The Fireman” occupies similar registral space, but its textures are continuous and open. Combining with the Fireman’s forming of a Golden Orb that will eventually bring the spirit of Laura Palmer into the world as a balm against the evil that was spawned as a result of the bomb, the sequence is visual and auditory catharsis. However enigmatic and difficult to pin down it may be, it reminds us that there are things that can resist the nightmare we have just paid witness to. As the woman from the parlor gives the Golden Orb a gentle kiss before setting it free into the world at large, we leave this fortress of refuge, and return to the real world in jarring fashion.

I’m going to reflect on this a little more broadly. The disjunctness of Threnody as contrasted with this sequence extends not just to the musical textures, but what we see onscreen. We were deprived of characters, of people, and while there is no dialogue here, it is a moment that borders on comprehensible. The Fireman and the woman are some desperate force for good, watching from afar as evil is birthed into our world. They must give of theirselves and hope that the good they try to give us in the form of the orb and Laura Palmer is enough. “The Fireman” track expands and contracts like something breathing, and overwhelms the soundscape much in the same way Threnody did. Has this too, become music as sound design? Not that they would have ever told us before, but now with Lynch and Badalamenti both gone… We will never know. And that’s the point of all of this, isn’t it?

Part 4: “Gotta Light?” (Sounds as motif)

11 years after the bomb has been detonated and we have witnessed these demonic atomic visages, Lynch deposits us in an unsettlingly normal New Mexico. A boy and girl walk back from a school dance, finding a penny along the way. A bizarre creature only describable as a frog-moth hatches from an egg. A couple goes on an evening drive. An oil-coated demon bearing the visage of Abraham Lincoln materializes in the desert. Things are not normal, and the following scene demonstrates that brilliantly. While the scenes with the boy and girl utilize only diegetic sound (conversation, footsteps in the sand, the whistling of crickets, etc.), the couple in the car is not so fortunate. Finding another car stopped in the road, they slow down and are ambushed by the Lincoln demon (hereafter referred to by his credit, as The Woodsman).

The sound design of this sequence is exquisite (an idealized example of trope #1), and as the supernatural intrudes upon the natural, the sound design shifts in kind from diegetic and realistic to the acousmatic/unrealistic and back again. This evolving pattern is a fantastic example of Lynch’s musical treatment of sound design (see McCorkle’s article again), which is found all throughout his work and exemplified in microcosm here. The following table helps to illustrate the relationship between onscreen events and the evolution of the sound design, and how Lynch uses sounds with similar timbral roots (natural and unnatural) to create a richly unsettling sound palette. In some ways, Lynch is taking basic foley work and orchestrating it almost in the same way an instrumental writer might orchestrate certain timbral shifts, so I think it’s fitting to describe this sound design approach as “Foley Orchestration.”9

Onscreen Events | Resultant Sound | Diegetic Y/N |

|---|---|---|

Couple is driving | Pattering hum of the car engine | Y |

They slow down and see the Woodsman | -car engine, + low buzzing drone | Y N |

He comes clearly into focus | +electrical burning noise | N |

“Gotta Light?” he asks at their car door. | +Distorted, gravelly and electric voice. | Y |

The woman begins screaming in slow-mo | +Low, slowed down wailing. | Y |

The couple escape their trance and speed away as quickly as possible | +Engine, screeching tires, -drone, voice, burning electrical sounds. | Y A little ambiguous, isn’t it? |

I would like to point out one detail that I couldn’t touch on due to restrictions in the length of the paper and subsequent presentation: That low drone is nigh identical to the same low drone that plays when the killer is revealed in the original series, and the distorted slow motion screams resemble what happens in That scene. 25 years forward and back. Pain and terror echoing across the decades.

The whole sequence is barely 90 seconds long, and yet in this brief span Lynch creates a deeply layered and constantly evolving sonic palette, continually blurring the lines between diegetic and non-diegetic. The drone and burning appearing in tandem with The Woodsman suggest diegesis, but as we will see shortly, this is Lynch using sound design as motif and blurring the lines of sound design and music through his association of pitched material and the electrical randomness of The Woodsman. While so often the unreal intrudes through sound in his work (think of Mulholland Drive’s trash man sucking the sound out of the scene upon his entrance), these sonic intrusions are rarely so prominent as in The Return. The unnatural intrudes upon the natural, with the soundscape modulating itself to match.

Part 5: My Prayer (and dark within)

After the driving couple escapes him, The Woodsman wanders through the desert, and out of the blue, the gorgeous voice of Tony Williams rings out. After a moment, The Platters’ song “My Prayer” is revealed to be coming from a local radio station, and we cut across several scenes of people listening to the radio. All the while, “My Prayer” plays in pristine quality, far greater than what what we could expect of 50s radio — we are hearing exactly what the DJ hears on his headphones as he listens to the broadcast. This play with aural fidelity helps to cement “My Prayer” as diegetic, but leaves it slightly unstable, just outside the purely diegetic soundscape10.

“My Prayer” functions as a gorgeous mirror to “She’s Gone Away” from the beginning of the episode, giving the audience a sort of sonic catharsis akin to “The Fireman,” now with traditional lyrical music. Where “She’s Gone Away” is distorted, driven by duple meter ostinato and Reznor’s screaming, “My Prayer” is clear as can be, with a gentle triplet ostinato, and the pure tone of Tony Williams’ voice. It could not be more of a contrast, and given the mood of this episode, it cannot last.

Nine Inch Nails, “She’s Gone Away” | The Platters, “My Prayer” |

|---|---|

Completely diegetic, performed in-universe | Diegetic, but lacks aural fidelity to the image |

Heavy distortion throughout | Clear, undistorted tone |

Intense duple ostinato | Light triplet ostinato |

Low, throaty, unpitched singing | High singing with immense clarity |

High whistling drone backing | Low-pitched choral backing |

Lyrics focused on painful imagery/distance/the past | Lyrics focused on joy/intimacy/the future |

Plays to completion | Violently interrupted |

Contrasted qualities of the two songs that feature in episode 8. These songs are diametrically opposed, but I have been thinking about how they both place strong emphasis on “gone.” Quite possibly a completely irrelevant observation, but something about it is sticking with me very intently.

The Woodsman enters the radio station, and after violently crushing the skull of the receptionist at the climax of the song, he forces his way into the broadcast booth. Grabbing the head of the DJ with an iron fist, “My Prayer” is cut short as The Woodsman rips the needle from the record. There is an interesting sonic shift here — as we cut around to the radio listeners, we hear distinct colors of static emerging from their radios — the blissful relief of the song has been cut short, and we are now trapped in the world with The Woodsman.

This last sequence of the episode is one of the most uncomfortable, particularly from a sound design perspective. In his deep distorted voice, The Woodsman begins reciting a poem, hypnotizing the radio listeners into a trance-like sleep. All the while, we hear the DJ’s skull slowly begin to crack while the man gasps and whimpers, a disgusting background layer to an already horrifying sequence.

Because I am no long constrained by page count, I am now including the poem in full:

This is the water,

and this is the well.

Drink full… and descend.

The horse is the white of the eyes,

and dark within.

This poem is another aspect of the episode that receives entirely “accurate” and faithful treatment in its sound design, and like the NIN performance at the beginning of the episode, this sharp focus forces the audience to engage with it. They can do nothing but watch this “performance” in horror, and it is a performance: Each time The Woodsman recites the poem, it is granted new life and inflection, and it climaxes on his final statement. The attention paid to accurate aural fidelity as the episode cuts between the booth and the various sleeping listeners is meticulous, and as surreal as the situation is, there is no evidence of diegetic ambiguity like elsewhere in the episode.

As The Woodsman recites, we return to the frog-moth that hatched earlier as it crawls its way through the desert. The care to the creature’s sound design is exquisite, as its body squelches and flutters, and the soft rustling of the sand as it drags itself through the desert. These squishes and rustles are somewhat complimentary to the sound of the DJ’s head being crushed, another instance of Lynch’s “foley orchestration” taking elements of unnatural and naturalistic sound design and blending them into a harmonious continuum.

Distant and tinny, The Woodsman’s voice fades back in, and with a flutter of its wings, the creature enters the room of a sleeping girl. The poem continues, the creature flutters some command at the girl, who opens her mouth and lets it crawl down her throat. The sound design is as uncomfortably detailed as you would imagine, and the inhuman voice on the radio reciting its refrain is of no help.

Returning to the booth, The Woodsman grows angrier in his recitation. Finishing his final verse, he slowly and deliberately shatters the DJ’s skull completely, building to an uncomfortably splatter-y climax. With that, he leaves the station and disappears into the dark and howling winds of the desert, as a distant whinny of a horse echoes back and forth.

During the credits, we see the sleeping girl, accompanied by the drone and electrical burning heard during the “Gotta Light?” sequence. She has been infected by the fallout of the bomb and the monstrosities it birthed. The exact nature of what infected her is ambiguous, but it is evident through sound and the surreal nightmare we have experienced that something is horribly wrong.

With that, we have a (microcosmic) rundown of Lynch’s sonic choices in episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return. So much of this episode’s treatment from a cinematic and narrative perspective is a landmark that left viewers utterly discombobulated, but the impact of the sound and music in this episode cannot be overstated. Through sound, this intensely abstract and unsettling episode is granted a striking sense of continuity and development through the way Lynch modulates between music, sound, and blurs the lines between both. There is more still in this episode that I did not have time to discuss, including a nighttime nightmare before “She’s Gone Away” that contains numerous parallels to the episode’s ending, to say nothing of the myriad implications this episode has on the sound design throughout the remainder of The Return. We will tackle that all in time.

To (try and) conclude, Lynch’s work with music and sound design is some of the most forward thinking and deliberate in the entire film medium: From this episode we see careful and subtle evolution of sound design as motif (“Gotta light?”), the way the episode is treated as a canvas where he can create long-term sonic development (“She’s Gone Away” and Threnody to “The Fireman” and “My Prayer), how Lynch centers performance as a way of forcing the audience to engage with a sequence’s emotions and themes, his deliberate appropriation of existing music to modulate our moods, and most noticeably, the care he takes in the most minute and exacting details. Indeed, some of these details are so subtle they are nigh unnoticeable without a good sound setup or high quality headphones. But these details of sound are there nonetheless, and are observable and rewarding for the attentive viewer.

After all, The Fireman tells us what to do at the very beginning of The Return, draws us in to the vital element of sound in Lynch’s work when he says:

“Listen… to the sounds.”

postlude

I could do even further analysis, but I would strongly encourage watching both Twin Peaks and The Return. As a work of fiction and work of art, it is one of the most astounding things I’ve ever encountered. The Return in particular feels like an apotheosis of Lynch’s art, every idea and dream coalescing into something devastating and beautiful. It was a farewell from Lynch to so many of his collaborators, a meditation on grief, nostalgia, and what it means for us to try and save the people we lost. I didn’t know David Lynch. But in his dreams of sight and sound, I feel everything. And one day, I hope to explain it in ever more detail.

His work brings a wholeness to my life I cannot begin to describe. “We live inside a dream” feels so true these days. And no one could paint a better dream than him.

this is not to say that the original Twin Peaks lacks detailed sound design, in many of the most famous and abstract sequences it does! But a few episodes with notable audiovisual sequences vs 18 straight hours of unfiltered Lynch shenanigans is, you know. A substantial difference. ↩

Not that anyone could have possibly predicted what was going to happen next… ↩

- https://music.mxdwn.com/2017/09/18/news/nine-inch-nails-wrote-shes-gone-away-for-twin-peaks-after-david-lynch-rejected-first-composition/

Reba Wissner, “Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima and the Trinity Atomic Bomb Test in Twin Peaks: The Return.” Musicology Now, December 21st, 2017. ↩

Robynn Stillwell, “The Fantastical Gap Between Diegetic and Nondiegetic,” in Beyond the Soundtrack, ed. Daniel

Goldmark, Lawrence Kramer and Richard Leppert (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007) 184–202. ↩Jeff Smith, “Reconsidering the Border Between Diegetic and Non-Diegetic Music.”Music and the Moving Image,

Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 1-25 ↩- https://musicologynow.org/theres-always-music-in-the-air-sound-design-in-twin-peaks-the-return/

- https://musicologynow.org/optigan-allusions-sonic-dislocation-in-the-return/

Wow good one there Haden, real smart-sounding. I’ve no issue with foley orchestration as a term now, it is just funny that this is me editing my old text so it’s slightly less excited with itself over the Exciting New Term. Anyways, I’m still right, but I was vaguely pretentious in the OG. ↩

Jeff Smith, “Reconsidering the Border.” ↩