Car Science: gulf edition

Hello! You're reading Car Science; please consider subscribing, it's free and helps me.

Hey,

You know what's coming up this weekend? The Monaco Grand Prix. Everyone loves a fun livery for that, don't they. A nice Gulf version. We love a nice pastel blue and orange, fun bit.

Well, in the words of Trent Reznor: that was the last guys, we're here to have a bad time. Today's email is about the Gulf of Mexico and quite how staggeringly fucked it really is. Let's dive right on in.

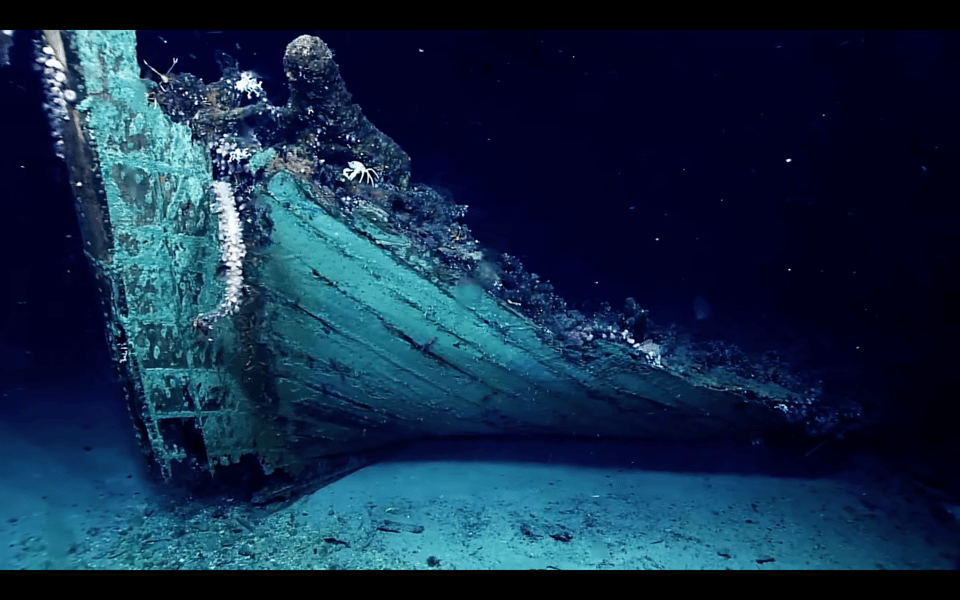

If, like me, you have two interests and they're cars and the weird stuff at the bottom of the sea then your YouTube recommendations probably look like: deep see remote operated vehicle streams in the Gulf of Mexico and wondering how many times you can tell the algorithm you don't want to watch old Top Gear clips.

Gulf wars

The Gulf of Mexico is that bit between Miami, Mexico and Cuba and one of the first things that comes up when you type it into Google is 'oil spill.' That's mostly because of Deepwater Horizon, widely regarded as one of the most catastrophic things we've ever done to the planet in a single event. Over 87 days 3.19 million barrels of oil slipped into the Gulf of Mexico, the largest marine spill in history and a crime that British Petroleum did not pay anything like enough for.

Deepwater Horizon is the big one and a disaster. But the Gulf of Mexico was being subjected to death by a thousand (fairly major) cuts anyway; by 2021 it gave us the chance to pause and consider the question "is it good that the sea is on fire?"

The Gulf of Mexico is so tremendously fucked that it's fucked in ways we actually didn't really account for, even allowing for massive horror events like Deepwater Horizon. Research published in April said that while deep water drilling might be getting the worst rep for, uh, y'know. That. There's actually something even worse about shallow water drilling, which is that it emits staggeringly high amounts of methane that isn't correctly dealt with. Even when 'correctly dealing with it' is just lighting it like a fart.

In fact - this will shock you because obviously everything we've learned about the gas and oil industry is that they are friends not just to you, me and the planet but also sea life and ecology at large - it turns out people aren't really maintaining shallow water rigs at all, let alone to the basic standards that might stop them acting like postmix cannons for the ultimate Wetherspoon's Pepsi enquiry of "is it alright if it's horribly damaging greenhouse gases?"

Which is making them leak even more methane, that isn't even being flared so it's just belching straight into the atmosphere. It's not even stuff we're using, it's not even fuel, it's just a messy byproduct of extracting things like clumsy morons that happens to be more-than-doubling the greenhouse gas emissions per unit on any fuel drilled out of the Gulf of Mexico because it's so heinously goddamned bad.

That's a huge bummer for anyone planning to continue existing on earth. But it doesn't actually have to be this way.

There was what could look like quite a bleak piece of research published on the 8th May, titled Financial liabilities and environmental implications of unplugged wells for the Gulf of Mexico and coastal waters

The conclusion the paper draws is that it would cost about $30 billion to plug up all the leaks on abandoned and semi-disused wells that just haven't been closed. Which, like; I'm a really messy person and I let the laundry build up but even I've never had a depressive episode where I left 14,000 wells unplugged in the Gulf of Mexico.

"A few paragraphs back this sounded like the positive bit, Hazel" - no, I get that and admittedly, it's not good. It's actually very bad. The paper points out what the one I mentioned earlier does, which is that even when they're not actively being used the onshore or shallower-water wells are much worse environmentally, in particular for leaking methane.

A narrow but legally-defined sense of mild optimism

So, what's good? Well, the great news is that 90% of the at-risk holes in the sea bed are in shallow water and those would only cost $7.8 billion to stop leaking horrible stuff, which is a significant saving to fix the vast majority of the problem.

Even better, though, there are people who actually have to do it and it's the oil and gas industry. At the same time as frantic applications from Chevron, BP, Exxon and Shell are going in to drill more holes in the sea bed, they have to provide some sort of environmental accountability - and they did back when these wells were dug.

Which means even if they've sold on the problem, if the wells are now disused and leaking then it's the hard-up petrochemical giants' job to fix this. $7.8 billion is extremely loose change to the four companies responsible for the majority of the destruction, so the way forward seems pretty clear, here.

Obviously we should not be drilling more holes for oil. The fight now and for the next 20-to-forever years is going to be trying to keep the carbon in the ground down there and shove more of it back in. But academia doing the work to make a case, legally and pragmatically, that companies have responsibility to clear up their mess before they can ask to make any more is an extremely useful piece of research.

So: there are things we can do and there are people who should be doing them and maybe even ways of forcing them to actually get them done. Which is a lot more optimistic than a lot of climate change-contingent disasters.

With rocks in

Other good news about sequestering carbon in the sea: there's an extinct volcano off the coast of Portugal in the Atlantic that researchers think could store gigatons of captured carbon. Volcanoes are good for carbon capture because they're full of what geologists call "rocks and stuff," a lot of which is mineral layers that will react well to carbonation. Blasting carbon through them as gas will result in a reaction that creates a new substance between the reactive volcanic materials and the carbon, effectively trapping it. And I've watched a lot of an Australian man trying and failing to make different chemicals recently but if the worst thing you end up with is some tar that politely stays the hell down there that's not actually all that bad.

The car bit

I realise I haven't actually mentioned cars at any point in this car-related newsletter yet, which is probably remiss. Something that came up a lot at Future of the Car and in calls I keep having with people in motorsport and with OEMs and governments and anyone you care to speak to in the things with wheels industry is: there are a lot of existing cars which all run on combustion fuels.

That's true. And they're not going to be magicked away any time soon. Even with combustion sales bans coming in from 2030, there's going to be over a billion vehicles still running on petrol.

What does that look like in the meantime? Well, we've got to stop taking that fuel out of the ground. Accelerating a ban or severe restriction on getting more oil out is going to be a critical factor in what we need to do - but then what will vehicles run on.

Long term readers will know what I think of synthetic fuel as a viable option for this: it's not. It's just too energy intensive to be a realistic solution at any scale and the level of efficiencies that would need to be found to make it viable defy physics.

But in the vague family of things PR people call sustainable fuel there is another option. Bio-derived fuels have a bad reputation for using cultivated feedstocks but don't have to be. They're still bad, carbon-wise; the idea of carbon-neutral combustion of hydrocarbons is chemical fiction but the advantage of biofuels is that they're more plausible at scale, energy-wise.

It also gives us the option of controlling decay on bio-waste via them, which should mean capturing methane. Methane might well be what tips things over now because there's a lot of it locked in glaciers and in frozen areas beneath ice that we haven't accounted for in climate change modelling - so we would need to control decay anyway. Using that process to make combustion fuels isn't ideal but in terms of pure realism is the best bad idea we've got, between continuing fossil extraction and the sci-fi never-never.

Ideally, we click our heels together three times and go back to an earlier point where we can fix this with softer solutions. But between the bad choices we have, bio-derived fuels (from waste, of which there is plenty) are looking like very plausible options. But you don't really hear much about them, since the 'carbon neutral' label got inaccurately applied to synthetics.

Anyway, just a thought there. It really is going to be all dodging between least bad decisions for quite a long time unless we discover fusion or something but it'd be a shame if one of those options got downplayed for the sake of something currently fashionable with venture capital.

Hazel

x

.

.

.

[I feel very awkward about this but people keep asking if I have a Kofi or whatever so yes I do it's here but zero pressure only if you really feel like you want to obv.]