Car Science: all aboard

Hello! You're reading Car Science; please consider subscribing, it's free and helps me.

Hey,

This is only going to be a quick one, which is the sort of stupid thing I say before writing several thousand words and also because I'm still writing up some really long things from Future Of The Car but: guys, we've got a big boat stuck in a body of water. I repeat, we've got a big ol boat stuck in a the river just outside Detroit and that means two things: it's time for Great Lakes shipping pollutant lobby history and also some stuff about iron ore used in the automotive industry that probably no one cares about so I'll put it at the end.

The Great Lakes, you've heard of 'em: probably because of that one song about that one boat with way too much iron onboard in bad weather. Lake Superior actually kind of gets a bad rep off Lightfoot's publicity when it's Lake Erie that really causes trouble, with a shallower depths meaning it has a particularly lethal combination of easily whipping up huge, vertical waves and freezing faster during a cold snap storm.

We're not here to talk about the catastrophic effects of ice storms on heavily-laden ships, though. But it is relevant that the thing you know about the Great Lakes, other than them being completely enormous is that they're used for shipping. Heavy shipping, stuff it's a nightmare to move any way other than boats like coal and iron ore.

And no, this isn't Boat Science. But there is a reason that the US automotive industry is up in Michigan and it's precisely because you can get the metals you need to make vehicles pretty easily there, say by getting them loaded up on a big old freight container and taking it down the Detroit River and ramming it stuck across the channel by Belle Isle. Hold on, that isn't what you want to do at all.

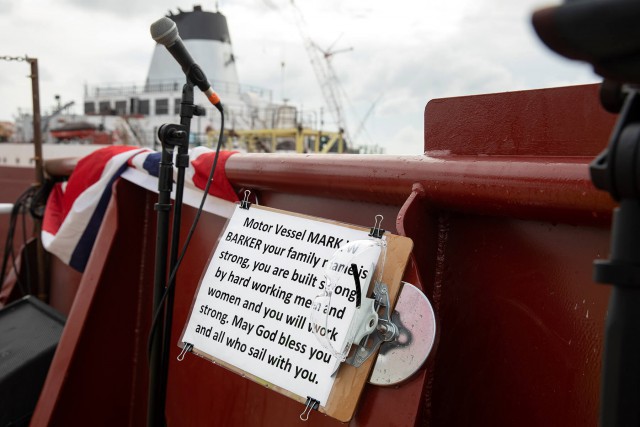

But that's what's happened to the M/V Mark W Barker, an Interlake Steamship Company freighter that's the internet's stuck boat of the day. Bless her, for she has come at our hour of need for some levity and nothing provides like a big, stuck boat.

That said, I keep calling her old and that's not actually true at all. She only launched last year, in July 2022 and she's easily the most modern freighter hauling on the lakes, the first one to comply to EPA Tier 4 standards that have been being introduced since 2008.

"Wait, what-" ok, let's get into it.

Heavy exceptionalism

EPA emissions rules for diesel engines aren't new. The US has been introducing emissions reduction standards for diesel engines over 50 horsepower since 1994. You don't have to have your whole executive board interrogated and some of them jailed to know, these days, that there are some pretty serious emissions associated with diesel engines.

Most of the time, people are keen that you comply with them. So how did 13 shipping companies on the Great Lakes get an exception to the EPA Tier 4 standards in 2009?

Well, the Great Lakes are big bastard bodies of water (my next grime EP, dropping 2024) but they're not saline, so boats suffer badly with what maritime experts call "suddenly sinking during ice storms" but don't decay in the same way that they do in the sea. As a consequence, the fleet of ships operating on them are older than the saltiest sea dog.

So old, in fact, that one of them is still literally a steamship operating with a coal boiler. The SS Badger is probably being refitted some time soon, although no one is quite sure of the timeline and in the meantime it's still a car ferry that's running on the crunchy black stuff. Although it may surprise you to find out she's actually only 70 years old, given that; America, what is going on with you. Even so, it's only needed a coat of paint once in 40 years, which shows you how little things are chipping off in the frigidly cold but nonetheless, gently fresh water of the Great Lakes.

Fire and brimstone

What was the big change that needed to be made? Well, ships would have had to run on fuel that was less than 1% sulfur. That might not seem like that much of a challenge, seeing as standard category D marine diesel is uhhhh 0.1% sulfur. So you'd need to be more than 10 times over the usual amount.

That overlooks, though, companies being good at being cheap. Most of the ships on the Great Lakes are staggeringly old. Great Lake ships run on what environmental groups in 2009 described as "the filthiest fuel known to mankind" which is some garbage at the bottom of oil tanks known as residual fuel. Unsurprisingly, this grotesque sludge has tens of thousands of times more bad stuff in it than standard fuel and comes at a cut price.

Most ships have actually cleaned up a bit since then. But nonetheless, there are exceptions to EPA standards for Great Lake ships. Which was why the MV Mark W Barker was such a big moment for interlake shipping because it was the first genuinely modern vessel. So, unfortunate that it's also currently getting publicity as a localised sort of Evergiven viewing platform to the IndyCar Belle Island round. (you're two months late, fellas)

Since 2012 there's been a scheme to convert the old steamers running on even worse things to, uh, residual fuel. Because that would be slightly less bad. But here we are, on the Great Lakes, absolutely steaming.

Get to the science bit, Hazel

Ok, ok. Ok. So the bit where this pertains to cars is actually something I've been wanting to write about for ages and maritime fun time aside: cars involve a lot of iron ore to make steel.

There's a separate, half-written draft about the fact steel's in short supply these days but even if we fantasise about a world where the blast furnace will never run out of fuel, making steel fucking sucks the big one. Which is why turning iron ore - which is shit, anyway, these days - to something easier to turn into steel is a good thing.

The ore that gets moved around on the Great Lakes to Detroit is as pellets, which is a format specifically for blast furnaces. There's ore, a binder and something like coal used to help the reduction process.

Which brings me to 2017 and the start of moving "Mustang" superflux pellets on the Mark W Barker's older sister, the James R Barker. Mustang superflux pellets use a higher level of calcium, which is highly reactive as commonly occurring things go and so means they reduce quicker and cleaner in the blast furnace.

Honestly, the whole bit of steel that isn't recovered is probably close to over. But while we're still smelting stuff we might as well try and do it in ways that are slightly less disastrous. And there are proven scientific benefits to this if you want to read a paper about it from 2016, especially given that globally there's a general trend (surprise! we're running out of good stuff!) that iron ore deposits are lower in iron content.

Anyway, there you go. Now you know something about the Great Lakes other than the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Hazel

x

ps: if you want to watch some Great Lakes content I really recommend Alexis Dahl and Michigan Rocks.