Boys Life's Brandon Butler on reunion, van fires and how "you can’t recreate 30 years ago"

BY GREGORY ADAMS

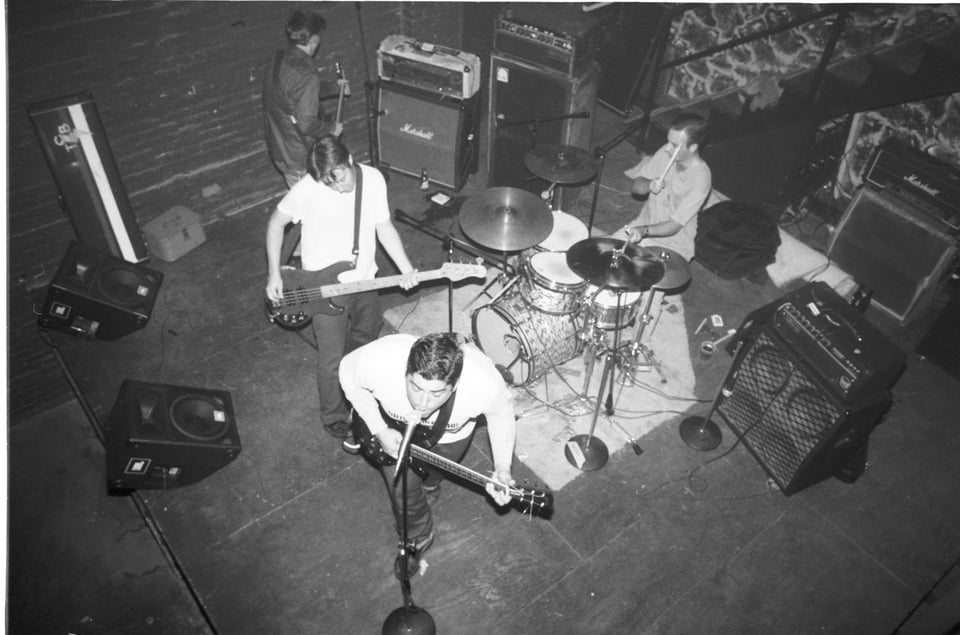

This past weekend, cult Kansas City, Missouri quartet Boys Life hit the stage for their first shows in almost a decade.

Both an all-ages gig in Lawrence, Kansas and a hometown bar show were played to celebrate the release of Home Is a Highway, a deluxe, career-compendium box set from archival specialists the Numero Group that includes two classic albums, their 1993 demo tape, their sides from split releases with Christie Front Drive, Vitreous Humor, Giants Chair and more.

It’s a stunning collection that showcases a dramatic arc of sound — from the Jehu-adjacent, amp-cranked post-hardcore bashes of their 1995 self-titled debut, towards the slow-roiling, cinematic, and often twangy crescendos of the following year’s Departures and Landfalls.

Speaking between the two shows, guitarist-vocalist Brandon Butler sounds stoked and grateful to be back at it with the rest of the band — guitarist Joe Winkle, bassist John Rejba and drummer John Anderson. But while a collective muscle memory kicked in for the quick-pivoted, even quixotic transitions of enduring emo anthems like “Fire Engine Red,” Butler acknowledges that it’s not been a 1:1 revisiting of their early sound, either.

After initially wrapping Boys Life up in 1997 (they’d reunite for a trio of shows in 2015), the members explored other styles of music: see Butler and Rejba’s extra-loud the Farewell Bend, Butler and Winkle’s Americana-exploring Canyon project, or more recently Anderson’s Suburban Eyes pop-rock outfit alongside former members of Mineral and Christie Front Drive.

Three decades on, they’ve gained life experience on-and-offstage. Butler’s voice has deepened with age. To walk you halfway there, there’s probably a clever quip to be made that they’ve transformed from “Boys” to “Men”. Suffice to say, Butler hears all those changes. Others have, too.

“Everyone is saying that this sounds like Canyon doing Boys Life songs,” Butler suggests of the band’s current iteration — familiar, but with a different flow. “It’s not tight in the mathy way that it used to be; it’s not abrupt starts and stops anymore. The equipment’s different. The playing style is different. You can’t recreate 30 years ago, it’s just not possible.”

To paraphrase Butler’s emotive yawl on Departures’ “All the Negatives,” the reunion shows and the box set have been a chance to fall down memory lane for a bit. On the other side of things, they also debuted multiple new songs that will end up on an upcoming EP via Seattle’s Spartan Records (who’d previously repressed a Farewell Bend album, as well as Suburban Eyes’ debut LP). Butler says these all sound “very different” than earlier Boys Life releases. They’d actually tried revisiting material left unfinished in ‘90s, but the vibe was off (“We had one older song, but it just didn’t work out. It didn’t transpose. So, we did four new ones”).

When Gut Feeling first reached out to Boys Life about an interview, Anderson suggested talking up Butler about the literal new sound of a recently-built custom Gibson SG. Turns out that’s more of a work-in-progress, with the neckthrough in question not making it out to the live shows.

“There were some upgrades that needed to happen to make it gig-worthy. So that it wouldn’t go out of tune,” Butler confirms of the custom six-string, noting he instead relied on a Les Paul-style body he’s turned to a ton over the years. “I’ve got an old ‘80s Tokai Goldtop that’s better than the ‘69 Goldtop I had when I was younger — it never goes out of tune.

“Tuning is such a bummer, you know,” he continues. “SG’s look cool and sound cool. With enough work they can stay in tune, but this one just kept going out on me at the house, so I just said, ‘Well...I’m not bringing that one.’ The Goldtop is my number one. That’s what I play most at home, and in my life.”

Speaking with Gut Feeling, Butler further weighs in on the Boys Life reunion, legacies and misconceptions, he and co-guitarist Winkle’s dynamic gear journey, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for flow and clarity.

When we’d spoken a few years ago around the Farewell Bend reissue, you’d said at the time that part of the goal of that band was to get loud again — “No moody music; nothing wispy or wistful” a la Boys Life. But then again, that’s not how Boys Life started out, either. What do you remember about getting this band off the ground?

BRANDON BUTLER: Well, we’d liked bands like Fugazi, Pitchfork, and DC hardcore like Jawbox. I think we wanted to put our own stamp on that, creatively, but we wanted do the Fugazi thing, where neither one of the guitars works well on its own. We didn’t really know what we were doing, either. I think that’s the key. [Ultimately,] we really didn’t have an agenda. And nobody was interested in us.

That’s what’s so weird about all this. I bought an amplifier off a guy the other day. He was in a band, and he said, “I’ve never been in anything on the level of Boys Life,” and I was like, “Let me explain something to you, we didn’t play to more than 30-40 people, mostly.” We’d played a couple times in Chicago, but by and large we’d spend six weeks on tour and the most people we’d play to would be 10-15 people. For entire tours! I told him that and he was looking at me like I had two heads.

People care about it now, but back then…if there was genuine interest in it, [there] would’ve been no reason to stop. We didn’t break up because we didn’t like each other. It wasn’t because we thought the music was bad. We stopped playing because it became apparent that we were just going to go on the same [level of] tour over and over again.

We get to hear the arc of the band on this box set, and how you’d changed over the years and between albums. That also goes for the ways you treated certain songs along the way. The demo version of “Temporary,” for instance, is significantly slower than the version from the self-titled album. How long did it take for you guys to literally find your rhythm?

BUTLER: There was a local band in Kansas City called Molly McGuire that had two guitar players. I’d never seen anybody do this until they did, but one guy would play the barre chord and the other guy would find the octaves that fit in the same key, and then there would be this dance between the chords and the octaves moving around like a lead. So, we were experimenting with that form. I took it from them — just saw what they did and stole it. [laughs] I tell [Molly McGuire’s] Jason Blackmore that to this day.

We weren’t confident, so some of those songs were slower at first. We had a different drummer at the time, too — a fella by the name of Dave Banaka. There was a personality issue there, and we just didn’t jive with him. John [Anderson] was in some other bands in town, and he was a great drummer. He was young, he could play well, and he was interested. [And] he was an excitable person. I think things sped up at that point, because John would play with more pep.

What was your rig like at the beginning of the band, and how much did it change heading into to the Departures and Landfalls period?

BUTLER: That’s pretty easy, we looked to what the Replacements were playing. We wanted a JCM Marshall 800 and a 4x12, but they were hard to find. That was a big investment for a kid, so [at first] I had a Mesa Son of Boogie, without the EQ section on it. We just wanted something loud, high powered, and with gain — speaker movement gain, not like a metal gain. Then we [got] Marshalls.

Then I got into bands like the Afghan Whigs and Sebadoh. I would watch those guys, and they all had Fender amplifiers, [which] were more atmospheric-sounding — open-backed and aired-out. Also, Boys Life went from humbuckers to single-coil pickups to develop a more aired-out sound.

So, I traded my Marshall stack for a Fender Twin. That was more the reverb-y, spacey, open sound. Throughout the years I would collect amplifiers, and then I’d do both — I’d play a Fender Twin and a Plexi.

I’ve said this before, and I think everyone in the band would agree, but we didn’t necessarily want to be an “emo” band. We wanted to be atmospheric. We wanted to play with band like June of 44, the Rachels, Mekons or PJ Harvey. Stuff that was more soundtrack-y or theatrical, not just straight up stuff.

Had we stayed with the Marshalls…you look at certain bands that were coming up the same time we were, and a lot of those band still have careers. They bought houses with their music…but that’s not what we wanted to do. [laughs]

Were volume pedals ever a part of your set-up, especially later on as you’re developing the dynamic, dramatic crescendos on Departures and Landfalls? Or was that more done with volume knobs and boosts?

BUTLER: Turning up and down and creating an atmosphere with volume…where a quieter part would draw you in and then it’s exciting when it gets loud again…we messed with those dynamics. We did it well enough in the studio and live. But that’s something that almost every guitar player gets into. I mean, it’s nothing new. Ry Cooder, Neil Young, Fugazi…it’s a universal trick.

We never played with effects pedals. And, like, they weren’t available! You could get a BOSS pedal, but that was about it. Now everybody in the world has a boutique pedal board with every gadget you could want. But the volume pedal…that was the trick. Some people would wedge a little block of wood underneath it, so they could get it to a particular volume. And then they step on it like a gas pedal. Joe still uses one. I’ve never used one, though. I use my finger on the volume pots.

How did you and Joe work parts out together?

BUTLER: I would come up with the protein of the meal, and he would come up with the sides. I mean, that’s pretty much it! “Here’s the basic song and you add things in.” He would vibe off that. That’s how it worked; that’s still how it works.

To do this music again is like unlearning, in a way. A lot of it doesn’t make sense. What he’s playing should not fit. There’s no theoretical pattern that makes it all work. But somehow, it kind of does.

Still, we’ve rearranged a few things to play these shows. And I can’t sing like I used to. It’s been hard, but it’s been interesting.

What’s gone through the most changes?

BUTLER: We shortened a song by about three minutes. It was seven minutes long, but we clipped an entire verse, because that verse was already in there once. Here’s what’s crazy: nobody noticed.

Which song was that?

BUTLER: “Two-Wheeled Train,” off the 10-inch [ed. their 1995 split with Christie Front Drive].

“Sleeping Off Summer” from Departures and Landfalls is one of the most fascinating and captivating songs in the Boys Life catalogue. What do you remember about developing that one, and how you all leant into the hypnotic groove of that extended drum roll section?

BUTLER: One of the things John’s pretty good at is these light stick rolls. He was in a drumline in high school, and that was in his bag of tricks. We did that on a couple of different songs.

It’s [got] a chord shape that I’d seen other people use. It’s sort of like a C shape, and you move it up and down [the neck]. All these songs can be transposed to first position cowboy chords, but they’re [played] in weird shapes and missing certain fingerings. [“Sleeping Off Summer”] is a good example of this. It’s the same part over and over, but it doesn’t get boring [because] we do two or three variations of it.

How about something like “Fire Engine Red,” where there is quite a bit more of that stop-start pacing, and a lot of drastic time changes. How intentionally were you exploring those songwriting variations?

BUTLER: I don’t know! We just wanted to prove that we could do both.

I was really surprised at how many people knew the count [to “Fire Engine Red”] last night. I could see their body language anticipating the stops — and it’s got weird stops! It’s meant to throw you. It’s meant to be odd. It’s four different hooks that don’t really tie together. We’re changing time signatures [more] by muscle memory, and as a result, people have learned the math of it.

But there are also a lot of [fans] that were 19-20 years old [when Departures and Landfalls came out]. That’s a pivotal time in a person’s life…and it just became part of their personal history. That was the soundtrack. It stuck in their heads.

Part of Boys Life’s history is this massive, and really traumatic-looking van fire that took place on one of your tours. How far into the band’s original run was this?

BUTLER: I don’t know how much touring we’d done, but we had enough money given to us for tour support — like, $3,000 bucks — and we bought that van. One night there was an oil fire on the top of the motor that caught the rest of the van on fire.

We rode home in a U-Haul that Joe’s mom or dad paid for with a credit card — we paid them back. This was around St. Louis. We loaded up our stuff and rode in the back of the U-Haul. We played a show that night with the Get Up Kids. After that we had a Ram van that Joe bought and we toured in that a couple of times.

Did you lose any gear in the fire?

BUTLER: A lot of clothing. And we didn’t have out shoes on at the time. I didn’t give a shit about the clothes or our tour journals, but we got all the merchandise and equipment out.

Back then, [gear] was so hard to come by [that] we risked personal injury and death. There was fuel everywhere. We were chucking amplifiers out the back, or pulling the cabinets out and sliding them across the parking lot. We got all of that stuff out, and then we sat back and watched the van burn. It had a big fiberglass top that caught on fire — the smoke looked like a nuclear explosion. I’m sure you could see it from 50 miles away. And that van just burned to the ground. That was a big van. Brand new tires on it. Those blew up.

It was hot, too. We got about 100 yards away from it and you could still feel how hot it was. That was wild.

You mentioned watching the crowd’s body language reacting to these older songs last night, but what was it like playing new Boys Life songs live for the first time?

BUTLER: It was strange! There were a lot of people there who were really young. We had some people come from Melbourne, Australia — a 19-year-old kid and his dad. That kid knows our music better than we do! His dad showed me on his phone how his kid had demoed all our songs on his guitar. Honestly, this generation of kids is 10 times more excited, organized and adept with their musical skills than we ever were. These kids today are bad-asses.

That band Flooding that opened? They sound fucking pro. Sweeping Promises are not a new band, but their sense of community and the way they run shit? Heads and shoulders above what we had. We can’t hold a candle to that. The fact that they allowed us to be there was great.

You’ve just put out the box set, but like you said, you also have some new music on the way. What’s excited you most about reuniting Boys Life this time around: falling down memory lane and acknowledging the history of the band, or connecting with these three guys again to make more music?

BUTLER: For the most part, I don’t go to shows. I don’t actively [spend time] on Instagram or social media. When I first heard [about the box set,] I didn’t know what Numero was. But the box looks and sounds great. It’s a great representation of what went on [in the ‘90s]. And I think that for somebody that doesn’t have access to all the original records or know the history of the band…you buy that box set and you’ve got every single thing you need. It’s all there!

I honestly think it was lightning in a bottle with the new songs. I had three songs; Joe came up with a riff to round it out to four. Spartan Records is going to put out the EP. We’re happy to tell people about that, and happy to be involved with Spartan…but I don’t know how much we can do to support it. I don’t feel like we’ll be an active band.

I think it’s good to present the past and turn people onto it, but I also think it’s good to step away and make room for other people to do shit. Let these kids do their thing! It’s not like we’re stepping on their toes or getting in the way, but [the music scene is] already oversaturated.

But…it’s also ok to leave a little calling card.