News from the Front Porch Republic

Greetings from the Porch,

We received some much-needed rain in central Michigan this week, and the flowers and plants here are looking lovely. Our rhododendron and peony are particularly vibrant this year.

-

In my weekly Water Dipper, I recommend essays about digital memory, local news, and seeking truth.

-

Nathan Beacom compares two Nebraskan narratives. Rural Rebellion, by Ross Benes, examines the changing politics of rural Nebraska from the perspective of a native son now living in Brooklyn. Nebraska is a cycle of poems by Kwame Dawes, a Ghanaian-born poet teaching at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Both address the identity crisis of our time and call us to remember the real names of things.

-

Zach Pritz reviews Enjoying the Bible, a book about beholding the deep riches of beauty in Scripture and allowing its literary elements to shape our humanity. A literary approach to Scripture teaches our students how to love rather than merely what to think.

-

Elizabeth Stice revisits Slacker and argues that it portrays a city and a scene that are delightfully different and offbeat. It suggests that you don’t have to leave the state or run off to the biggest city to do something big: there is a real beauty and opportunity in the less-sung places.

What’s on the docket for next week? An interview with the author of a new book on Leviticus and liturgical time, a review of Age of Anxiety, an essay on mutualism, and a consideration of what healthy masculinity might entail.

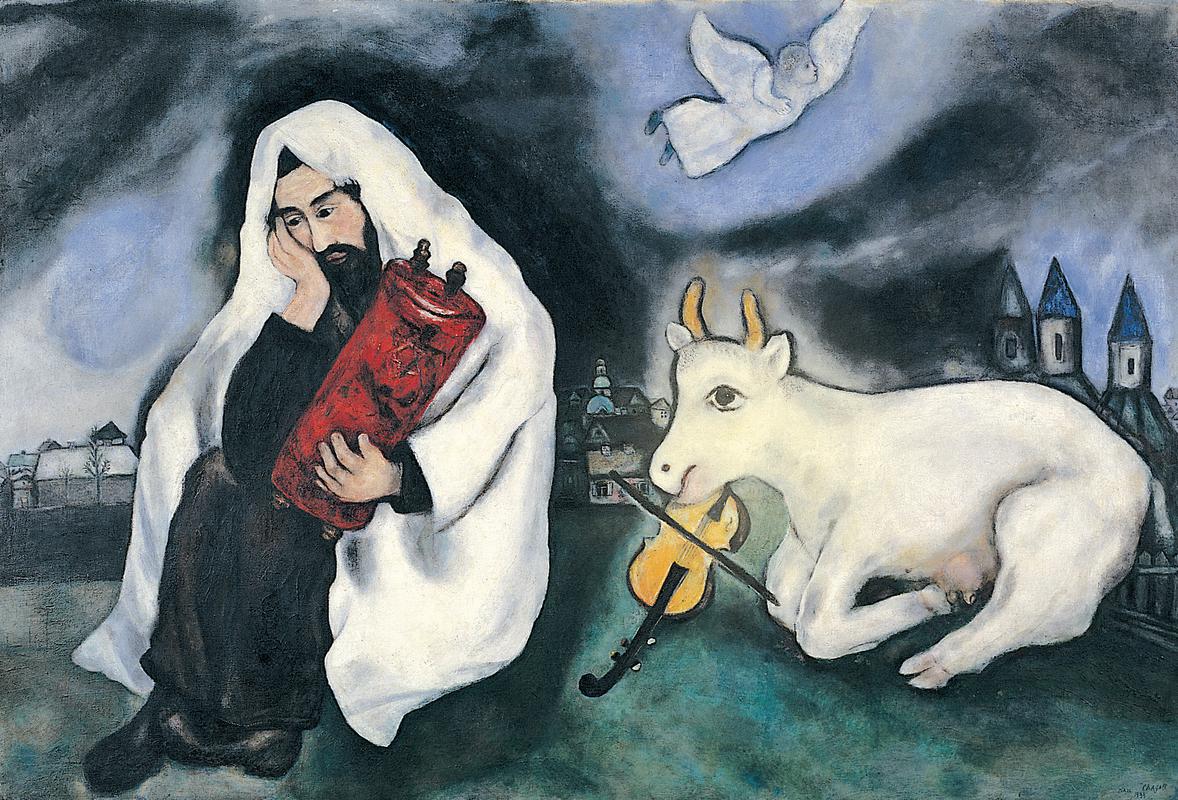

This coming week, my book Reading the Times: A Literary and Theological Inquiry into the News comes out. I’ve been grateful for the many thoughtful reviews that have already been published. I thought I’d include a couple paragraphs from the book where I reflect on a painting by the Jewish artist Marc Chagall, Solitude.

In 1933, as Hitler’s Nazi party rose to power in Germany, the Jewish artist Marc Chagall painted Solitude. In the foreground, a seated man sits wrapped in a tallit or prayer shawl. His right hand supports his head in an attitude of contemplation, and his left arm embraces a large Torah scroll. At his side, a heifer seems to be playing a violin. In the background the city of Vitebsk—where Chagall was born and raised—is shrouded in darkness and watched over by an angel. At the time he painted this, Chagall was working “obsessively” on a commission to illustrate the Old Testament, while also keenly aware of the looming clouds of Nazi anti-Semitism. Indeed, one of the Nazi’s first examples of “degenerate” Jewish art was a painting by Chagall.

In the midst of these disturbing political developments, Chagall drew on the Jewish tradition of deep, loving attention to the Scripture. The violin-playing cow is an image of the imaginative, artistic meditation on the divine Word being practiced by the man cradling the Torah scroll. Why a cow? Because the Hebrew word hagah, like the Latinate English word ruminate, means both “to meditate” and also “to chew the cud.” David Jeffrey links Chagall’s painting to this trope, explaining that “by analogy with the peaceable heifer, a spiritually flourishing person is said to be one who meditates on the Word of God, day and night.” One of the iconic Old Testament passages that relies on this wordplay is Psalm 1, where the blessed man “delight[s] in the law of the Lord, and on his law he meditates day and night.” The result of this meditation is not just some kind of personal enrichment: the psalmist compares the person who ruminates on God’s Word to a tree “planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season, and its leaf does not wither.” The result of scriptural rumination is fruit that blesses one’s place and community. The rooted life of the blessed man contrasts with “the ungodly [who] are like the chaff which the wind driveth away” (Ps. 1:2-4). These chaff-like fools are blown about by the latest fads and trends; in this way, they are like those with macadamized minds. A Christian image for healthy attention, then, might be this rooted tree—or a violin-playing heifer.

In Chagall’s painting, the meditative figure is not ignoring the events of his time and place in order to lose himself in solipsistic, irrelevant flights of fancy. Rather, he is feeding on the eternal truths most needed in this turbulent historical moment. As one of Chagall’s biographers notes, this painting is part of Chagall’s own response “to the omens heralding the destruction of the world that had nourished him.” Crucially, in the background of the painting an angel—suggesting divine providence—is watching over human affairs even when they seem imponderably dark to human eyes. Chagall’s composition suggests that trust in divine providence and an imaginative attention to the Word of God provide the proper perspective from which to view the events of our day.