Episode 4 - Fungal products everywhere, part 1

Welcome to Filaments! I’m Silvia Hüttner, and this is a limited-run newsletter which tells the stories of how fungi have been, are and will be changing the world. You’re getting it because you signed up at buttondown.email/filaments and you can unsubscribe at any time with the link at the bottom of this email.

Hello fungi friends. It’s been a while. 😊 I started a new job and that took a bit of my time and headspace. In my new job I work a lot with enzymes, which are made by microorganisms, often fungi. So that’s an excellent reason to use this episode of Filaments to dive into the MASSIVE - but to many people unknown - business of enzyme production in filamentous fungi. (If you need a refresher about filamentous fungi (moulds) and their use as food and materials, go here). Also, this is a fairly long episode, so make yourself a cup of tea, and enjoy. 🍵

EPISODE 4 - Fungal products everywhere, part 1

Inspect a package of washing powder and you will likely see some or all of the following ingredients: Subtilisin, cellulases, mannanases, pectinases, proteases, lipases, amylases. These are all enzymes - proteins that speed up certain chemical reactions. Enzymes are precision tools that usually do one job, and one job only, and that job is often to chop up longer molecules into smaller ones.

Cellulase cuts cellulose - a polymer consisting of long chains of sugar molecules - into smaller pieces. Protease breaks down proteins, lactase cuts the milk sugar lactose into glucose and galactose, and so forth. A lot of the enzymes in detergents break down things that come from food and dirt that might be on our clothes, such as greasy sauces (lipases), fruit juice (pectinases), cake batter and mashed potatoes (amylases) or body fluids (proteases). By enzymatically cutting these substances into smaller components, they are more soluble and more easily removed.

This is (kind of) how an enzyme works (if it was a person). Credit: Christian Winter

Although enzymes are made by all organisms, including animals and plants, most of those contained in our everyday products and used in industry are produced by microorganisms, i.e. fungi and bacteria (and we obviously focus on fungi here).

Fungal enzymes are used in a vast number of different industries: in agriculture, research and wastewater treatment, in the production of animal feed, pharmaceuticals, alcohol, fuel, juices, beer, bread, dairy products, cleaning products, textiles, leather, sugar, meat and paper, and a lot more. They permeate everyday life to an extent that few people realise.

The filamentous fungi used for enzyme production are grown in much the same way that filamentous fungi for food production are grown (as described in Episode 2).

Walk into the production site of a large-scale enzyme producer such as DSM, Novozymes, BASF or Amano, and you will see huge, several storey-high stainless steel tanks, holding up to 300 000 L of liquid. These fermentation tanks (or bioreactors) are filled with a particular species of fungus that produces the desired enzyme, and a nutrient solution containing mostly sugar or other low-cost carbohydrate source - often from grains - and some salts. The tanks are set to the perfect temperature and pH for the fungus to grow in, big stirrers mix the liquid and make sure everything is well distributed, and air is bubbled through the liquid from the bottom and the sides of the tank to provide necessary oxygen to the fungus.

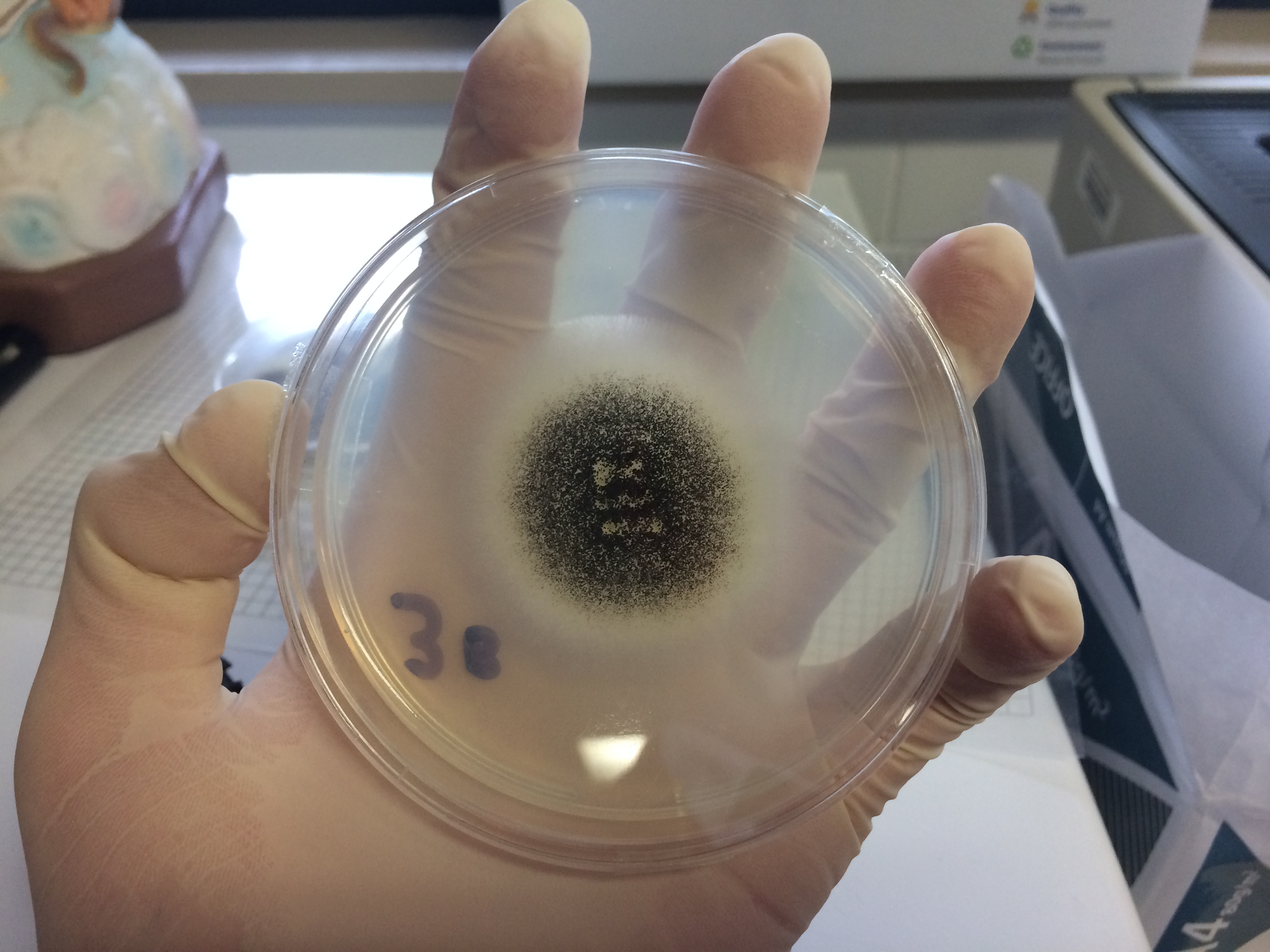

Fungal growth and enzyme production doesn’t start in these enormous tanks, though - it happens in steps. First, fungal cells that are stored at -80C are revived in a petri dish where they grow in a beautiful mould pattern. (Technically, step 0 would be finding and isolating the fungal strain in nature; we’ll come to that in a future episode).

Step 1 in fungal enzyme production: an Aspergillus niger colony that has been growing in a petri dish (on potato dextrose agar) for 3 days. Source: Wikimedia

Step 1 in fungal enzyme production: an Aspergillus niger colony that has been growing in a petri dish (on potato dextrose agar) for 3 days. Source: Wikimedia

The freshly grown fungal cells from the petri dish are then transferred to a small bioreactor (several litres) and after a day or so the fungal mycelium has grown into a thick filamentous network of billions of interconnected cells, and is ready to be transferred to a larger tank (several hundred litres). There it grows for another day, continuously increasing in mass, until the mycelium is finally transferred to the big main tank where the cells continue to multiply and multiply over several days. The reason for this stepwise process is that the requirements for healthy growth as well as the risk of contamination by other microorganisms can be much better controlled this way.

During this multiplication and growth process, the enzymes (the actual products here), are produced by the fungal cells in the tank and continuously secreted into the liquid. The more fungal cells there are, the more enzymes are made and released into the liquid, until the billions of fungal cells in the tank are surrounded by a soup of trillions of nanometre-sized enzymes. All this takes just a few days, and in those few days the slurry of enzymes and fungal mycelium gets thicker and thicker.

Step 4 in fungal enzyme production: the main fermentation tanks can hold up to several hundred thousand liters. Source: BRAIN Biotech.

Step 4 in fungal enzyme production: the main fermentation tanks can hold up to several hundred thousand liters. Source: BRAIN Biotech.

All that’s left to do then is to separate the enzymes from everything else in the tank. But first, let’s talk about where the fungi - the stars of the process - actually come from.

In the wild, many fungi have evolved to secrete digestive enzymes which break down plant matter into nutrients that the fungus can take up easily. Usually fungi secrete a whole cocktail of different enzymes, each with a very specific function. In an industrial process, however, we usually only want to produce one kind of enzyme. So how do we do that?

Well, it turns out that the nutrient source, pH, aeration, and salt and mineral additions and concentrations, etc. all influence what kinds of enzymes a fungus produces. Modern fermentation technology is a highly controlled process and has become so optimised that - if everything runs smoothly - the fungus will produce little else than one particular target enzyme.

And of course the type of fungus plays a huge role as well. The workhorses of enzyme production haven’t actually changed much over the last century, and are Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae and Trichoderma reesei.

A.niger is the fungus that causes black mould on fruits and vegetables (niger means black in Latin) and is used in a wide range of industrial processes, mostly in enzyme and acid production. A. niger makes different amylases - enzymes that break down starch - which are used for example in beer brewing (to improve the malting) and baking (to make fluffier bread). A. niger also makes glucose oxidase, an enzyme found in biosensors such as blood glucose test kits for diabetes and other clinical applications.

The other Aspergillus, A. oryzae, is also called koji in Japanese and has been used for centuries in Southern and Eastern Asia to make fermented rice, barley and soy products like sake, soy sauce and miso. It’s still used for these purposes, as well as in many other areas, because of its natural capacity to secrete large amounts of different starch- and protein-degrading enzymes.

Aspergillus oryzae growing on rice for the production of miso. Source. Wikimedia.

Aspergillus oryzae growing on rice for the production of miso. Source. Wikimedia.

Finally, T. reesei is mostly used in biofuel production, since it produces enzymes that break down cellulose and other plant polymers to sugar that can then be converted to ethanol in a yeast fermentation process. The original T. reesei strain was isolated during WW2 as the cause for rotting (i.e. “eating”) the tents and clothes of US Army soldiers stationed on the Solomon Islands. Today its enzymes are, besides biofuel production, also used to give stone-washed jeans their distressed look and they’re added to washing powder to remove loose fibres that can cause textile pilling.

To achieve an even higher purity or higher concentration of one particular kind of enzyme in production processes, most enzyme companies also use genetically engineered fungal strains (as opposed to so-called “wild-type” or “classical” strains). Again, Aspergillus is a popular choice, because it grows well, is safe to use and there is more than a hundred years of scientific literature available about it. The gene for a specific enzyme can be inserted several times into the host genome, thereby drastically increasing the production of enzyme per cell. In addition, the enzymes themselves can also be further optimised through biotechnological tools. By carefully adjusting the protein sequence of an enzyme it can for example become more resistant to high temperatures.

Genes from other organisms can also be inserted into the Aspergillus genome, which makes it possible to produce enzymes that this fungus originally wouldn’t be able to make. Let’s take an example. Rennet (or more specifically the protease enzyme chymosin) is a crucial component of cheese production, and was originally extracted from the stomachs of slaughtered calves. This quite wasteful and cruel practice became obsolete when scientists managed to insert the gene coding for the rennet enzyme into the genome of a fungus. So nowadays, more than 90% of cheese produced worldwide uses chymosin made by a genetically-engineered organism, often a strain of Aspergillus niger. Compared to the traditional way of rennet production, this reduces cruelty, cost, carbon emissions and pollution in the process.

Cheese, likely made using fermentation-produced chymosin. Source: Wikimedia.

Cheese, likely made using fermentation-produced chymosin. Source: Wikimedia.

Most enzyme companies on the market offer both “classical” enzymes, for users that prefer non-GMO-derived ingredients, as well as enzymes that have been engineered and/or have been produced in GMOs. Just to clarify, however: while “classical” enzymes don’t come from fungal strains that have been changed with modern biotech methods, i.e. genetic engineering, they still have been optimised over the years by “classical” methods. Usually numerous rounds of random mutation (for example by exposing the fungi to gamma-radiation or DNA-altering chemicals) and selection of the best-performing strains, until desirable traits are achieved (similar to plant breeding). Their cousins in the wild would probably not recognise them any more, and the industrial strains would not survive long without their precisely adjusted cultivation conditions.

As mentioned above, enzymes are used in a wide range of industries and products. But why are they still relatively unknown as ingredients? Well, because they are not exactly ingredients. One of the reasons that enzymes fly under the radar, particularly in food products, is that enzymes are considered processing aids and therefore are not declared on the ingredients list on the package. One single enzyme molecule can catalyse the same chemical reaction millions of times, and so a little goes a long way, and most products only need the addition of minute amounts of enzymes (less than one gram of enzyme per ton of raw material). Furthermore, enzymes only work when the right conditions are provided. As soon as the temperature is sliiightly too high, the enzyme is irreversibly destroyed. When food is heat-treated to kill off any microorganisms in the product, the enzymes added during production are taken care of at the same time.

So back to the process of enzyme production by fungi: what happens to the fungi after they’ve fulfilled their job as enzyme producers? After a few days of happy growth and enzyme secretion in the fermentation tank, all available nutrients in the liquid have been consumed by the fungal cells. The density of mycelium and enzyme has reached a maximum. Now, the fermentation broth is released from the tank and pumped into a large filtration unit where the liquid containing the enzymes is separated from the mycelium, either in a spinning washing machine-like drum, or in big filter presses that squeeze the last bit of liquid out of the mycelium, which at this point resembles wet cotton.

The liquid is then further concentrated to reduce the volume and finally a thick, viscous, honey-like substance chock-full of enzymes is obtained. This liquid is either shipped to customers directly, or spray-dried to get a fine enzyme powder. For specialised research and medical applications, where purity is a particular concern, an additional purification step removes even the smallest non-enzyme particles in the final product (such as some remaining nutrients, fungal metabolites, etc.).

The filtered-off fungal mycelium is heated to kill the cells and then dried and milled into a powder. This fungi powder can then be used as animal feed or as fertilizer and spread on fields. So in a nice example of circularity, the nutrients in the fungal cells may help grow the grains that will then again be used as a nutrient source in a future fungi fermentation process.

In the next episode, part 2 of “Fungal products everywhere” we’ll meet our friend Aspergillus niger again and dive into the acids and pharmaceuticals that fungi make. Until then, enjoy the rest of May!

Thank you for subscribing to this limited run newsletter about the fascinating things fungi can do and how we can use them. My name is Silvia Hüttner, I’m a biotechnology PhD, fungi enthusiast and a researcher specialised in fermentation and enzyme technology. I’d love to hear from you if you have any questions, comments or suggestions, or just want to say hi. Just hit reply. 🍄