One Should Not Camouflage Capitalist and Imperialist China as “Socialist”

Reprint of a Spectre article by Michael Pröbsting.

Every historic period has its “big questions.” One of the most debated among Marxists in the last years is the issue of imperialism in general and the class character of China in particular.

Recently, Immanuel Ness and John Bellamy Foster, two US-based scholars, have each published a long essay in which they try to apply the Marxist theory of imperialism to the conditions of the twenty-first century.1 Both are progressive authors, and Foster is also the editor of the well-known magazine Monthly Review.

In their respective essays, the two academics criticize what they call “Western Marxism.” They accuse the representatives of this tendency of failing to understand the nature of modern imperialism and, consequently, of adapting to the Western powers. Ness denounces several authors, including myself, as “neo-conservative Marxists” and “New Cold War theorists” who supposedly “support the expansion of US dominance in Eastern Europe, East Asia, West Asia, Africa and beyond.”

While Foster and Ness make a number of largely correct criticisms of several left-wing authors who ignore or underestimate the relevance of imperialist superexploitation of semicolonial countries (the so-called Global South), both fail to understand the essence of the Marxist theory of imperialism. Worse, they advocate a policy of support for the new Eastern Great Powers, praise China as a “socialist” country, and make the case for the ideology of a “multipolar world system.”

Ness and Foster’s essays suffer from a number of theoretical weaknesses—starting from their borrowing of the mechanist philosophical concept of Stalinism (the idea of one “principal contradiction” to which other “side contradictions” are subordinated) to their erroneous understanding of Lenin’s theory of imperialism. However, in this essay, I will limit myself to critique of their thesis that China is a “socialist” country.2

Restoration of Capitalism in the 1990s

Ness and Foster consider imperialism to be a US- or Western-led political system. It will be interesting to see how they explain the recent Trump-Putin rapprochement and the resulting split between US and European imperialism. In any case, they believe that China is an anti-imperialist and “socialist” state. As Foster writes:

More difficult still for those seeking to characterize China as imperialist in the classical sense is that rather than seeking to join the U.S.-dominated rules-based imperial order or to replace it with what could be considered a new imperialist order, Chinese foreign policy has been geared to promoting the self-determination of nations, while opposing bloc geopolitics and military interventions. Beijing’s threefold Global Security Initiative, Global Development Initiative, and Global Civilization Initiative together constitute the leading proposals for world peace in our era. The People’s Republic of China has few military bases abroad, has not carried out any overseas military interventions, and has not engaged in wars at all except in relation to the defense of its own borders.3

Ness similarly characterizes the USSR before 1991 and China (as well as North Korea) today as “actually existing socialism.”

This is absolute nonsense. In fact, as we have elaborated in other works, China became a postcapitalist state dominated by bureaucratic dictatorship after 1949. After the brutal crushing of the workers and students in May-June 1989 and the cul-de-sac of the previous policy of limited market reforms, the leadership around Deng Xiaoping moved to restore capitalism in the 1990s.4

The result has been a radical transformation of labor relations, the emergence of both a new bourgeoisie and a large private sector, and the capitalist restructuring of state-owned industry. Today, most employees work outside the state sector, whose share of total urban employment declined from 61.0 percent in 1992 to 22.7 percent in 2006. A World Bank report published in 2019 estimates that state-owned enterprises accounted for between 5 and 16 percent of employment.5 According to another World Bank report, wholly or majority state-owned firms accounted for 40 percent of real value added in manufacturing in 1998, but for less than 7 percent in 2013.6

The character of China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) itself had also drastically changed in the 1990s and 2000s. They no longer operate as part of a bureaucratically planned economy as was the case before capitalist restoration took place in the early 1990s. Since then, through a series of reforms, China’s SOEs were radically transformed and started operating on the basis of the capitalist law of value. By the end of 2001, 86 percent of all SOEs had been restructured and about 70 percent had been partially or fully privatized. Many enterprises were either merged or closed. According to the then-minister in charge of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, 3,080 SOEs—with 199.54 billion yuan (24.1 billion USD) of nonperforming loans written off—were closed down or went bankrupt in the years between 1994 and 2002.7 The number of SOEs fell from 64,737 in 1998 to 27,477 in 2005. From 1998 to 2004, six in ten SOE workers were laid off.8 To put it in absolute numbers, according to official figures, about 50 million workers were laid off between 1993 and 2004.9

In the course of this process, many SOEs have undergone a mixed-ownership reform. Over four thousand privatization projects have been carried out by central SOEs from 2013 to 2020, with private capital investment reaching a cumulative amount of 1.5 trillion yuan. By 2020, more than 70 percent of central SOEs have implemented mixed-ownership reform, resulting in the share of private capital in central SOEs rising from 27 percent at the end of 2012 to 38 percent.10 As a result, profits massively increased in the SOEs. While the average Return on Assets of such enterprises was only 0.7 percent in 1998, this figure rose to 6.3 percent in 2006.11 As explained by The World Bank: “Many SOEs were corporatized, radically restructured (including labor shedding), and expected to operate at a profit….As a result, the profitability of China’s SOEs increased.”12

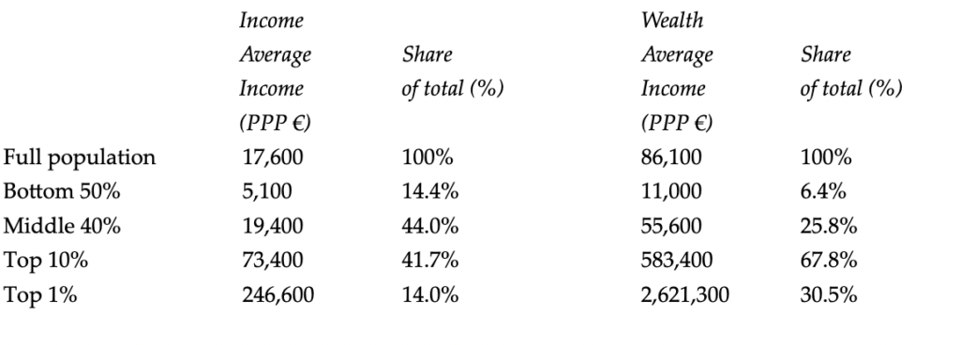

An international comparison shows that the profit rate of China’s monopolies is not in bad shape in relation to their Western rivals. While China’s corporations in the Fortune Global 500 list—of which two-third are state-owned—had a lower profitability than those from the United States or United Kingdom in 2020, their profitability was higher than their Japanese and Western European rivals. (See Table 1)

Table 1. Profit Margin of the Fortune Global 500 Corporations, 202013

The Emergence of a New Bourgeoisie

As the process of capitalist accumulation evolved, a new bourgeoise emerged in the 1990s. By the end of 2024, the country’s 55 million registered private enterprises made up over 92 percent of all businesses in China.14 While the state-capitalist sector continues to play a key role in the economy, private capital has massively expanded its position among the largest corporations. The share of SOEs among China’s top one hundred listed companies declined from 78.1 percent in 2010 to 51 percent in 2024. (Bear in mind that, as mentioned above, such SOEs often have a minority share of private shareholders.) The share of companies with mixed-ownership (these are firms in which the state owns an equity stake between 10 and 50 percent) stagnated at about 14 percent, while the share of private corporations has increased to 34.4 percent.15

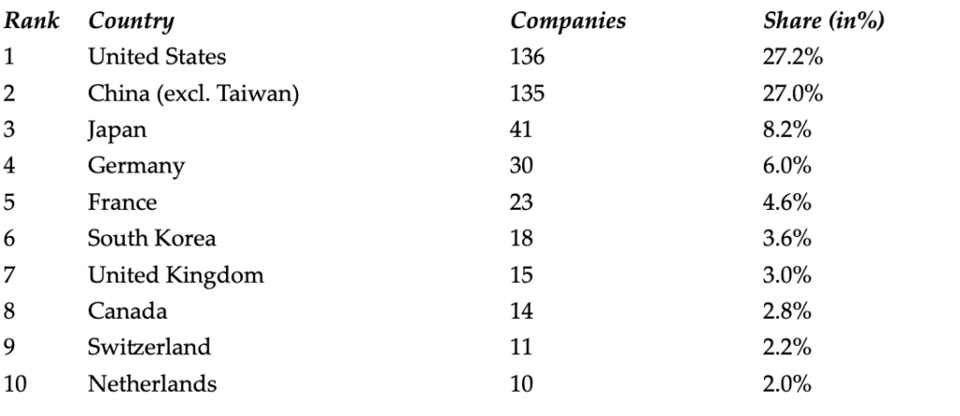

Consequently, social inequality increased dramatically, and income and wealth have concentrated in the hands of the ruling class and the upper middle layer. Before the beginning of the reform process in 1978, the share of national income going to the top 10 percent of the population was 27 percent, equal to the share going to the bottom 50 percent. This changed massively in the following decades and by 2015, the income share of the bottom half was just below 15 percent while the share of the top decile had increased to 41 percent.16 The elite’s share of national wealth has increased even more. The top 10 percent own 67.8 percent and the top 1 percent own 30.5 percent! (See Table 2)

Table 2. Income and Wealth Distribution in China, 202117

A research team around the progressive economist Thomas Piketty has demonstrated in a recently published book that the level of private wealth concentration in China (30.5 percent) is now nearly the same as in India, somewhat below that of the United States and clearly higher than that of Western Europe. In India, the top 1 percent own about 33 percent of private wealth, in the United States the share is 35 percent and in Western Europe it is about 22 percent.18 Likewise, as Piketty, Yang, and Zucman note in another paper, the Chinese top decile has a wealth share (67 percent in 2015) which is getting close to that of the United States (72 percent) and is much higher than in a country like France (50 percent).19

In other words, “socialism” in China exists only in official textbooks and party congress speeches. Economic and social reality demonstrate that the country had already become capitalist three decades ago.

China’s Rise as an Imperialist Power

China is not only a capitalist state. In the years after the Great Recession of 2008, it has also become an imperialist power. Today, it is home of 31.8 percent of global manufacturing, more than double the share of the United States.20 It is the leading exporter of goods (17.5 percent) and is second—behind the United States—in outbound foreign direct investments.21

Critics try to relativize China’s large global share in manufacturing by referring to the role of Western corporations operating in China. But such an objection is unfounded. Foreign multinationals operating in China account for about one-quarter of the output value and the profits of the industrial enterprises. In other words, the large bulk of China’s manufacturing output and profits are controlled by domestic corporations.22 Furthermore, the foreign companies operating in China are unexceptional and not unique to China, as such corporations also play a sizable role in Western economies.

Many Chinese companies successfully operate on the world market. The largest capital exports by Chinese corporations since 2020 have taken place in three sectors—automotives, basic materials, and energy—collectively accounting for a peak of 77 percent of total FDI in 2024.23

According to a report from the Rhodium Group, in 2024 Asia was the top destination for Chinese outbound investment for the sixth year in a row. New investments in Europe declined for the second consecutive year and continued to shift from Western Europe to Southern and Eastern Europe, with Serbia and Spain as top destinations in 2024. North America’s role continued to shrink with only $7.1 billion or 7.7 percent of total announced investment. Combined Chinese FDI in North America and Europe dropped to the lowest level since 2010. On the other hand, the so-called emerging markets in the Global South saw a greater share of total Chinese investment. Africa and the Middle East both recorded their highest-ever levels of announced Chinese FDI transactions in 2024. Chinese FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa reached an all-time high of $15.2 billion, representing 16.5 percent of newly announced investments in 2024.24

China’s corporations increasingly direct their outbound greenfield FDI from the Western imperialist countries away to the Global South.25 “Saudi Arabia was the largest recipient of Chinese FDI in 2023, with a 10 percent share capital investment. In Asia, 8.4 percent of outflows were directed towards Malaysia, 7.5 percent in Vietnam, 5.2 percent in Kazakhstan and 5 percent in Indonesia. In Africa, Morocco and Egypt attracted 6 percent and 5.1 percent respectively. In Latin America, China invested 4.8 percent of its global outflows in Argentina and 3.7 percent in Mexico. Meanwhile in Europe, Serbia was the main beneficiary with a 4 percent market share of outward China FDI.”26

In 2019, corporations in the semiconductors sectors received nearly half of their revenues from overseas; those in information technology about 37 percent. In the same year, China had 9 among the world’s top one hundred nonfinancial multinationals by foreign assets (United States 19, France 15, United Kingdom 13, Germany, 11 and Japan 9).27

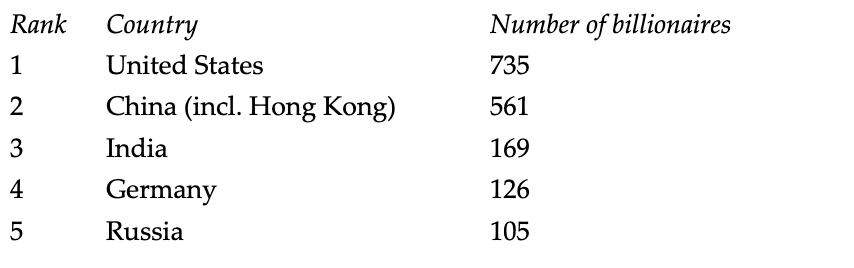

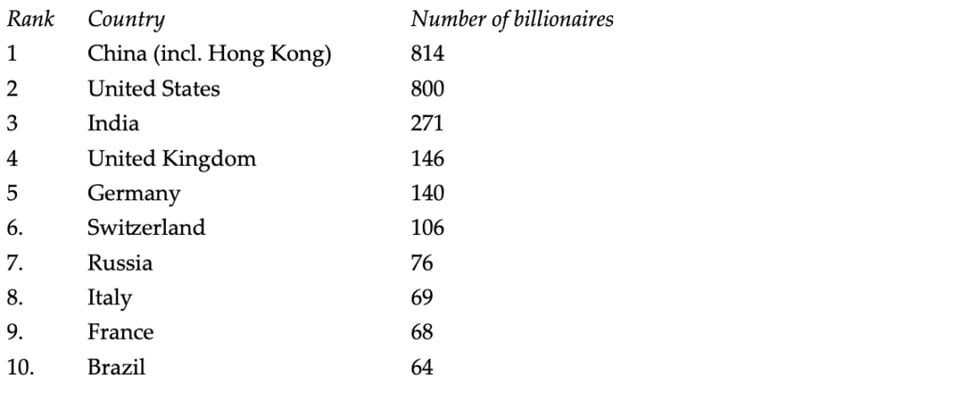

Based on their rejection of Lenin’s characterization of imperialism as monopolism, Ness and Foster believe that they can downplay the global rise of China’s economy as something secondary. However, China did not only become a leading power in terms of industrial output and trade, but also in terms of corporations and individual billionaires. Consequently, by now the Middle Kingdom is able to challenge the hegemonic position of its American rivals. (See Tables 3–5).28

Table 3. Top 10 Countries with the Ranking of Fortune Global 500 Companies (2023)29

Table 4. Top 5 Countries of the Forbes Billionaires 2023 List30

Table 5. Top 10 Countries of the Hurun Global Rich List 202431

In his essay, Foster argues that China has still been exploited by Western imperialist corporations over the last decade:

Low unit labor costs of goods produced in the Global South have led to widening gross profit margins for multinationals from the center of the system, whose commodities are produced in China and other developing countries and then exported to be consumed in the Global North, where the final selling price of the goods is many times [higher]. As Minqi Li has shown, China in 2017 experienced a net labor loss in foreign trade…, which was equal to forty-seven million worker years; while the United States experienced a net labor gain in the same year of sixty-three million worker years…In this fundamental respect, China is still very much a developing country.32

There is no doubt that Western corporations have gained from foreign investments in China in the past. However, if one makes a total balance sheet of the past three decades, it is evident that China’s monopolies have benefited many times more from the capitalist exploitation of Chinese workers than their American rivals and that the former have massively improved their position vis-à-vis the latter. How else can Foster explain the challenge posed by China’s corporations and billionaires to the United States today in contrast to those corporations marginal role in the 2000s? If there would have been a net surplus in favor of the United States, the latter should have been able to improve their position vis-à-vis China. But, as the growing share of Chinese corporations among the global leading monopolies indicates, these monopolies have gained much more from the massive expansion of China’s economy than their American rivals. We can also see this development in China itself where the revenue share of foreign-invested companies in total revenues of industrial enterprises in China declined from nearly 32 percent (2005) to 20.4 percent (2023).33

Contrary to Foster’s implication, the surplus value of the exploitation of China’s workers—many of them superexploited as internal migrant workers with little legal protection or access to social services—primarily went into the pockets of Chinese capitalists, not to their US competitors.

Yes, China’s Economy Is Less Developed than the United States’s, but…

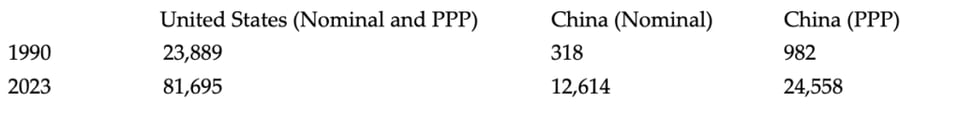

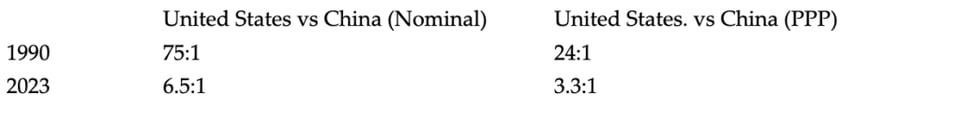

Foster is of course right to point out that the United States has a higher productivity than China. But this is hardly an argument against the imperialist nature of the latter. First China has rapidly closed the gap between itself and the United States. As one can see in Table 6 and Table 7, the United States’s per capita income was 75 resp. 24 times that of China in 1990 (depending on the method of calculation). Today it is only 6.5 resp. 3.3 times that of China. In other words, while China was an economic “dwarf” in terms of productivity thirty-five years ago, this is certainly no longer the case.

Table 6. United States and China GDP Per Capita in 1990 and 2023 (in Nominal and PPP US-Dollar)34

Table 7. Comparing United States and China GDP Per Capita in 1990 and 2023 (in Nominal and PPP US-Dollar)35

Secondly, the view shared by many Marxists that the United States is the exemplary imperialist state—and the further assumption that any less-developed state cannot be imperialist—is grossly mistaken. As I have argued elsewhere, Lenin and other Marxist theoreticians considered both the most advanced powers of their time (like Britain, Germany, or the United States) and more “backward” ones (like Russia, Japan, Italy or Austria-Hungary) to be imperialist.36

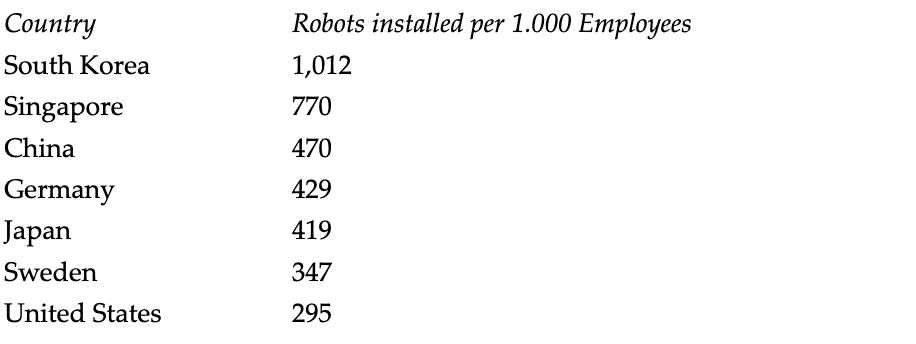

Thirdly, it is crucial to understand the uneven development of China’s economy.37 Its central and western provinces are much less economically developed. On the other hand, if one takes key industries into account, China is competitive with its Western rivals. The current global arms race in AI development, 5G, chip production, and other high-tech industries shows this very clearly. This becomes more evident when considering China’s strong position in industrial robots. Today, it alone possesses 31 percent of all industrial robots; China’s number of robots installed per employees in manufacturing is higher than that of Germany, Japan, or the United States.38 (See Table 8)

Table 8. Robot Density in the Manufacturing Industry in 202339

Foster argues that “in sharp contrast to China, the United States over its history has intervened militarily in 101 countries, some of these multiple times.”40 It is certainly true that the United States, as the imperialist hegemon for many decades, has a bloody history of military interventions abroad. China, as an imperialist newcomer, does not have quite a comparable record. Likewise, it is also correct that the United States still has a larger military than its Eastern rival (or anyone else).

However, as previously mentioned, US imperialism is not the only type of imperialism, and many imperialist states have undertaken hardly any military interventions since 1945 (for example, Germany and Japan). Furthermore, China has also started to demand complete control on its mare nostrum by claiming the complete South China Sea (China’s designation of what Vietnam calls the East Sea) at the cost of all other neighboring countries. This sea is one of the most important routes in global maritime trade (60 percent of global maritime trade and more than 22 percent of total global trade passes through it) and it has huge reserves of oil and natural gas. Finally, China is catching up in the military sphere and has become the world’s second-largest arms spender and third-largest nuclear power.

More fundamentally, while Foster and Ness downplay the economic dimension of the Marxist characterization of imperialism—with monopolies at its core—they place heightened emphasis on its military dimension. As a result, only the United States (and its allies) is left as an imperialist power.41 This reveals another similarity between their understanding of imperialism and Kautsky’s: both define imperialism on the basis of foreign policy, rather than its fundamental economic and political characteristics.

As Lenin once noted: “Kautsky divorces imperialist politics from imperialist economics, he divorces monopoly in politics from monopoly in economics in order to pave the way for his vulgar bourgeois reformism, such as ‘disarmament,’ ‘ultra-imperialism’ and similar nonsense. The whole purpose and significance of this theoretical falsity is to obscure the most profound contradictions of imperialism and thus justify the theory of ‘unity’ with the apologists of imperialism, the outright social-chauvinists and opportunists.“42

In conclusion, we characterize China as an imperialist Great Power because it is a capitalist state whose economy, corporations, and billionaires are among the strongest in the world and which operate on all continents. Likewise, it has one of the largest armed forces and plays a key role in world politics.

This brings us to the question of how Marxists should define an imperialist state. The formula, which we have developed in past works, and which seems to us the most precise, is the following: An imperialist state is a capitalist state whose monopolies and state apparatus have a position in the world order where they first and foremost dominate other states and nations. As a result, they gain extra profits and other economic, political, or military advantages from such a relationship based on superexploitation and oppression.

Such a definition of an imperialist state is in accordance with the brief definition which Lenin gave in one of his writings on imperialism in 1916: “…imperialist Great Powers (i.e., powers that oppress a whole number of nations and enmesh them in dependence on finance capital, etc.)….”43

Pro-Eastern Social Imperialism as the Political Consequences of a Flawed Theory

The political consequences of Ness and Foster’s mistaken theory are evident: they put the world on its head. For them, imperialism is basically a political power relation resulting in superexploitation of the Global South, not the epoch of moribund capitalism characterized by economic and political monopolism that results in both the superexploitation of the (semi-)colonial countries and interimperialist rivalry. For them, China—a rising Great Power challenging US hegemony—is not imperialist, not even capitalist, but rather a socialist state spreading the message of peace and welfare!

Consequently, they advocate for the creation of a “multipolar world order” as a progressive step forward. In reality, the unipolar and the multipolar world order are just two political versions of one and the same global imperialist system; one is dominated by the United States and the other is characterized by rivalry between several Great Powers—as was already the case in the first half of the twentieth century. Socialists should advocate neither one nor the other, but need to support workers and popular struggles against all Great Powers in order to replace the imperialist system with an international socialist alternative.44 But Ness and Foster advocate support for China and its allies. According to Ness, China and its allies “seek a multipolar world based on the principles of mutual respect found in the Charter of the United Nations.” Surely, Russia—China’s most important ally—has demonstrated such “mutual respect” in its military intervention in Syria in 2015–24 or in its ongoing war against Ukraine! And China’s suppression of workers’ protests and the Muslim Uyghur people in Xinjiang—which Fosters’ Monthly Review shamefully justifies—also reveals the hollowness of “actually existing socialism.”45

It is only consequential that Ness accuses people like me, who have sided with the Syrian and Ukrainian people against Russian imperialism, as “neo-conservative Marxists” and “New Cold War theorists” who supposedly “support the expansion of US dominance in Eastern Europe, East Asia, West Asia, Africa and beyond.” In the field of theory, Ness and Foster refute Lenin’s analysis of imperialism, and in the field of politics they are apologists of China’s Stalinist-capitalist dictatorship.

In the history of the workers’ movement, Marxists had to deal repeatedly with “socialists” who sided with one or the other Great Power. Usually, these forces supported their own bourgeoisie. However, there have also been several occasions where they sided with the ruling class of the rival of their “own” country. In World War I, some “socialists” in Russia sympathized with Germany and some German socialists with France. Likewise, German and Austrian social democrats supported the Western powers against their “fatherland” from 1933 to 1945. The Stalinist parties of these two countries followed a similar policy in the decade after 1935–except in the first two years of World War II where they switched to a pro-German course due to the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

While the formal arguments differed, their essence was essentially the same: the imperialist rival of their own ruling class was “progressive” or simply the “lesser evil.” This was justified by claiming that these powers were “more democratic,” had “fewer colonies” or followed a “less aggressive foreign policy.” For example, in the period of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, leaders of the Communist International characterized British imperialism in 1940 as “the most reactionary force in the world” whereas they claimed that Germany would have been interested in peace.

Lenin and the revolutionary Marxists in the early twentieth century denounced support for any imperialist power—irrespective if it was more or less “democratic” or if it had more or less colonies—as utterly reactionary.

“From the standpoint of bourgeois justice and national freedom (or the right of nations to existence), Germany might be considered absolutely in the right as against Britain and France, for she has been ‘done out’ of colonies, her enemies are oppressing an immeasurably far larger number of nations than she is, and the Slavs that are being oppressed by her ally, Austria, undoubtedly enjoy far more freedom than those of tsarist Russia, that veritable ‘prison of nations.’ Germany, however, is fighting, not for the liberation of nations, but for their oppression. It is not the business of socialists to help the younger and stronger robber (Germany) to plunder the older and overgorged robbers. Socialists must take advantage of the struggle between the robbers to overthrow all of them.”46

Consequently, they characterized the “advocacy of the idea of ‘defence of the fatherland’” as “social-chauvinism” or “social-imperialism.” “Social-chauvinism, which is, in effect, defence of the privileges, the advantages, the right to pillage and plunder, of one’s ‘own’ (or any) imperialist bourgeoisie, is the utter betrayal of all socialist convictions and of the decision of the Basel International Socialist Congress.”47

Later, revolutionary Marxists called those “socialists” who sided with the imperialist rival of their own ruling class “inverted social-imperialists.”48 Unfortunately, Professor Ness and Foster belong to such a category. They are pro-Chinese social-imperialists.