October: High season in the park

Frontenac State Park Association newsletter

October 2025 (Vol. 3, No. 10)

Comments, contributions, compliments, complaints? Reach your newsletter editor at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com.

October: High season in the park

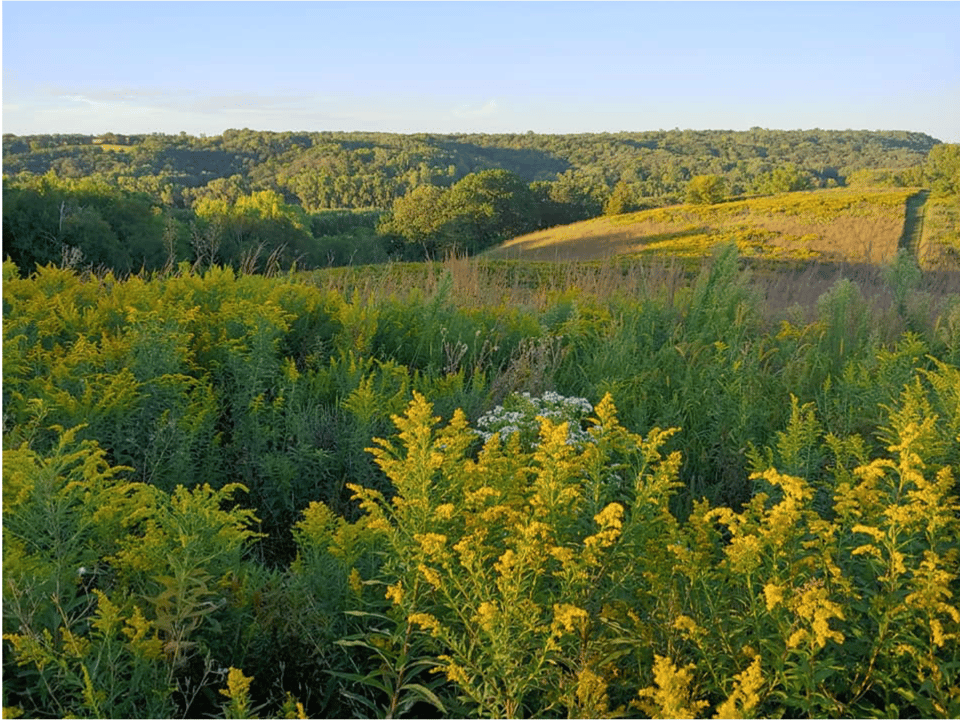

October! As you may recall from last October’s newsletter (we know you remember every word from our past three years of newsletters!), October is the most popular month to visit and/or camp in Frontenac State Park. The cool weather and vivid colors attract so many nature lovers — and yet you’ll find the park doesn’t feel especially crowded, even on a sunny Sunday. Come check it out!

And if you feel like joining an activity organized by your Frontenac State Park Association, here are some cool ones:

Tuesday, Oct. 7, 10-11 a.m.: Nature Explorers program on spooky critters for preschoolers with interpretive naturalist Sara Holger. Little kids love Sara, and these sessions! Meet at the main picnic shelter, near the upper parking lot.

Saturday, Oct. 11, 10-11 a.m.: Guided nature walk with interpretive naturalist Bruce Ause. Meet at the campground shower building kiosk. This will be Bruce’s last walk of the season.

Saturday, Oct. 18, 9-11 a.m.: Guided prairie bird walk with Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteers Janet Malotky and Steve Dietz. Meet at the campground shower building kiosk. Walk through a mixed habitat of prairie and woodland looking for late migrating and over-wintering birds. The trail is mowed grass and well maintained. Bring your binoculars or borrow some from the park office. Questions? Email janetmalotky@gmail.com.

Saturday, Nov. 8, 9-11 a.m.: Guided Sand Point bird walk with Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteers Janet Malotky and Steve Dietz. Meet at the Sand Point Trail parking lot at the southern intersection of Hwy. 61 and County Rd. 2. Walk through the riparian forest and along the beach to Sand Point for late fall migration. We will look for various waterfowl, including large flocks of Common Mergansers and Common Goldeneyes as well as Bald Eagles. Bring binoculars. The trail is well maintained and flat. The full loop is approximately 2 miles long, but you can head back whenever you need to. Questions? Email janetmalotky@gmail.com.

Thursday, Nov. 13, 2 p.m.: Quarterly meeting of Frontenac State Park Association. Main picnic shelter.

Saturday, Nov. 15, 9 a.m.-noon: Invasives work day. Details to come in November newsletter.

Saturday and Sunday, Nov. 22-23: Park closed for annual deer hunt.

Friday, Nov. 28, 10 a.m.-noon: Gratitude/forest bathing walk with interpretive naturalist Sara Holger. Meet at the park’s main picnic shelter.

Friday, Nov. 28: Free day at the park; admission waived.

Creature feature: Let’s talk … snakes!

By Pamela Miller

Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

Every now and then, we like to run a feature that could be called “Ask Jake,” in which we pester park manager Jake Gaster (or assistant manager Amy Jay) about something-or-other. After braking a surprising number of times recently on Goodhue County Rd. 2 near the park to avoid big snakes lolling on the toasty asphalt, your newsletter editor (who keeps a large stick in her vehicle just for wrestling off the road ornery foxsnakes or gophersnakes showing off their rattlesnake mimicry) decided it was time to talk snakes with Jake.

First things first: DO brake for snakes. Minnesota has 17 species of them, only two of which are rattlesnakes (the threatened timber rattlesnake and the endangered, possibly even extirpated, massasauga rattlesnake — no one has reported seeing one in Minnesota since the 1950s). Snakes play a vital role in our ecosystems, helping maintain the balance of rodent and other populations. Nature, Mabel, is like a game of Jenga — take away one piece and the others go haywire.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has an awesome booklet about state snakes that you can find online. (Note to young parents: We’ve found that this booklet makes surprisingly good Halloween time bedtime reading for small children — it’s fascinating without being scary.) But it’s also fun to pester the affable Jake, and so we did.

Here’s our Q&A with him about Frontenac State Park and snakes:

Q: Frontenac State Park is home to several species of snakes. Can you name a few we might see in Frontenac State Park?

A: Sure! The Western foxsnake, common garter snake, DeKay’s brownsnake, common watersnake and bullsnake. The park is also prime habitat for timber rattlesnakes, though none has been confirmed within the park for decades.

Q: Is the timber rattlesnake the only venomous snake that lives in the park? Are there any records of anyone being bitten by one in the park — or, in fact, in Minnesota, ever?

A: Yes, it is the only venomous snake in the park, though not in Minnesota; the Eastern massasauga is the other venomous snake, which has only been reported in Wabasha County [and as noted above, in the DNR’s snake booklet, not seen for decades]. There are no records of anyone having been bitten at Frontenac State Park. However, timber rattlesnake bites have been reported across Minnesota, predominantly here in the southeastern part of the state. That said, most timber rattlesnake bites occur when people intentionally handle rattlesnakes — often while under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Q: Where might timber rattlesnakes live in our park?

A: In Minnesota, the timber rattlesnake is a threatened species due to historical bounties and habitat loss. Its preferred habitat in our park would be among the many south-facing bluffs, particularly in the less developed western reaches of the park, where there are ample rock outcroppings and ledges for overwintering dens, with nearby forests and prairie for summer feeding grounds.

Q: Describe the life cycle of a timber rattlesnake.

A: Female timber rattlesnakes do not reach reproductive maturity until they are at least 6 years old, sometimes even 10 or more. They breed only every two to three years, when they will give birth to around seven live young. Given this low birth rate, it is suggested that for a population to remain viable, there must be 30 to 40 snakes per den, with around five fertile females. Mating takes place during summer and fall, with birth occurring a year later, in late August or September. Newborns remain with their mother for the first couple of weeks of life, after which they must fend for themselves.

Q: What do timber rattlesnakes eat?

A: They are ambush predators who mainly eat small mammals but have also been known to eat birds, insects and amphibians.

Q: Have you or [assistant park manager] Amy [Jay] ever seen one in the park? Or gotten reports of visitors seeing one?

A: No current park staffer has seen a timber rattlesnake in the park — and we’ve been looking! We get a dozen or more reports per year of visitors who think they have seen one. But for those visitors able to capture a photo of the snake they saw, every single time it has been a Western foxsnake or bullsnake in their photo, not a rattler.

Q: In the unlikely event a park visitor encounters a rattler, what should they do?

A: Simple: Give it ample space, enjoy the opportunity to have seen one, then take a picture on your phone and show it to park staff, because we want to see it!

Q: In the extremely unlikely event a park visitor were bitten, what should they do and NOT do?

A: Do call 911 immediately, and snap a photo of the snake if you are able so medical personnel can verify if the snake is venomous and, if so, which antivenom is needed. Even if you are bitten by a timber rattlesnake, half of its bites are dry, without any venom, and the venom is often not lethal even when it is there. You should not panic, attempt to kill the snake (doing so could lead to further bites), or ignore the wound.

Q: Why should we brake for snakes?

A: Snakes are a healthy and productive part of our ecosystem. They should be protected, as much as possible.

Bird note: Sand Point bird highlights, over time

By Janet Malotky, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

Looking for a fascinating field trip? Here’s one: The Bell Museum on the University of Minnesota campus in St. Paul bills itself as Minnesota’s official natural history museum, and more than fits that bill. Established in 1872, the Bell moved to its new, state-of-the-art building in Falcon Heights in the summer of 2018. It is a wonderful place to visit, kid-friendly but also fascinating for adults. Its dioramas of real places in Minnesota are highlights claimed by the Bell as some of the best exhibits of their kind in the nation.

So what’s the local connection? When wandering through the museum, you will be delighted to come upon a familiar scene depicted in one large diorama — our own Sand Point on Lake Pepin. Created in 1940 by preeminent background artist Francis Lee Jaques and foreground artist Walter J. Breckenridge, the diorama portrays a spring landscape.

Its three-dimensional foreground blends seamlessly into the painted lake and Wisconsin bluffs beyond. What looks from a distance like a calm pastoral scene shows its most arresting stuff up close, with detailed depictions of plants and animals that could be found at Sand Point at that time. There are more than 20 species of birds alone.

Dioramas are fun to explore, inviting us to spot and identify hidden animals, but have value beyond their entertainment opportunity.

This panoramic depiction of Sand Point is a snapshot in time. Comparing it to the Sand Point of today can reveal changes over time, including the impacts of river management (dams), agricultural runoff, population shifts and climate change. For example, no pelicans appear in the scene, but these birds are one of the point’s most common visitors during both spring and fall migration nowadays. The large bird on the right with raised wings, a Whimbrel, has not been reported in Frontenac State Park to eBird since that record-keeping app’s launch in 2002. Black Terns, numerous in the diorama, are rarely seen now. And there have been only two sightings on the point of a Piping Plover, listed as endangered in the Great Lakes region, reported to eBird.

A copy of the diorama image can be seen on the Frontenac State Park sign at the Sand Point parking lot. How does it compare to your experience at Sand Point?

Notes from the field: Sumac: the good, the bad and the zesty

By Steve Dietz, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

If you ever want to get into a verbal food fight with mild-mannered gardeners, bring up the topic of sumacs. They’re native! They’re aggressive! They’re beautiful to look at! They kill the view of everything around them! I hate them! I love them!

The good

I used to be in the hater camp, but once I needed to reclaim our steep hillside from buckthorn, dame’s rocket, ditch lilies, panic grass and other unwanted flora, I realized the true value of sumac.

While there are about 250 species of Rhus — sumacs — that grow on every continent except Antarctica, in Frontenac State Park, we have smooth sumac (R. glabra) and staghorn sumac (R. typhina) — and yes, these are native species. While similar looking from a distance, up close, staghorn sumac has distinctly fuzzy branches and fruits, while those of the smooth sumac are hairless.

The word sumac comes from the Arabic “summāq” meaning "red." Which is exactly what both species are, very red and gorgeous, beginning in mid-summer with their flowers and lasting through their winter berries. According to the USDA, they serve as an emergency winter food for wildlife. Ring-necked pheasant, bobwhite quail, wild turkey, and about 300 species of songbirds include sumac fruit in their diet. It is also known to be important in the winter diets of ruffed grouse. Fox squirrels and cottontail rabbits eat sumac bark. White-tailed deer like the fruit and stems.

Sumac grows vigorously in a wide range of soils, providing excellent erosion control on steep slopes as well as bountiful habitat for wildlife. Every spring, when sumac are denuded of their leaves and flowers, I unfailingly find several bird nests in them an arm’s length from where I regularly hike.

The bad

Ok, I admit there is some wiggle room in that term “vigorously.” Sumac self-seed and once established can spread — quite vigorously — through shallow underground roots. And while average heights are 8 feet (smooth) to 18 feet (staghorn), they have been known to grow to over 30 feet in optimal conditions.

Some falls, I have walked through tunnels of sumac in the park. Mechanical cutting and prescribed burns will help keep their colonization in check, but the real answer is to not put them where you do not want to see them overwhelm — say, in a formal garden or as a hedge that may quickly become an impenetrable maze. Elsewhere, they are unalloyed good.

The zesty

To top it all off, cooks have used a sprinkle of sumac for hundreds of years and longer. While historically, many culinary uses have been from R. coriaria, native to southern Europe and western Asia, local foragers and cooks swear by staghorn and smooth sumac. The berries are a good source of vitamin C and antioxidants and can be used to make “sumac-ade.” Dried and ground, they are an ingredient in the Middle Eastern spice za’atar, and can be used solo to pack a lemony punch in soups and stews, and to season meat and vegetables. I have acquaintances who use it like salt. In addition, the Native American Ethnobotany Database lists 108 uses for smooth sumac and 53 for staghorn sumac, many for treating common ailments.

Hater or lover, we can all appreciate amazing sumac, especially as fall turns toward winter.

The beauty around us: Notes from Bruce Ause

Interpretive naturalist and treasured friend of the park Bruce Ause has granted us permission to feature his blog entries in our newsletters. This month, we loved his observations about the natural world’s swift and dramatic sweep from summer to fall, not to mention an account of a strange encounter in the wild with … a little lost pigeon.

Poem of the month

“The Night Will Never Stay”

By Eleanor Farjeon (English; 1881-1965)

The night will never stay,

The night will still go by,

Though with a million stars

You pin it to the sky.

Though you bind it with the blowing wind

And buckle it with the moon,

The night will slip away

Like sorrow or a tune.

Interested in joining the FSPA?

If you are a member, thank you! You help us pursue our mission of supporting this treasured park in myriad ways.

If you’d like to join us, we’d be honored to have your support. Dues are $25 per year for an individual, $35 for dual/family membership. Here’s a link with signup information.

A reminder that joining us occasionally to help with volunteer efforts is awesome too, even if you’re not a member. The FSPA’s goals are to support Frontenac State Park activities and share our love of this beautiful park with as many people as possible.

To sign up to regularly receive this free, spam-free monthly newsletter, click on “Subscribe” below. Feel free to send questions or comments to your newsletter editor at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com. Questions about the FSPA? You can reach hard-working FSPA chair Steve Dietz at stevedietz@duck.com.

Handy links for more information and education

Frontenac State Park

Frontenac State Park Association

If you take pictures in the park, tag us on Instagram

Frontenac State Park bird checklist

Frontenac State Park on iNaturalist

Parks & Trails Council of Minnesota

Website for our township, Florence Township

Minnesota Master Naturalist programs

Red Wing Environmental Learning Center

Lake City Environmental Learning Program on FB

Visit Lake City

Zumbro Valley Audubon Society

Bruce Ause’s Wacouta Nature Notes blog

Marge Loch-Wouters’ Hiking the Driftless Trails blog

Frontenac State Park staff

Jake Gaster, park manager; Amy Jay, assistant park manager; Amy Poss, lead field worker

Parting shots

Thank you, readers and park visitors!

This is Volume 3, No. 10 of the Frontenac State Park Association newsletter, which was launched in April 2023.

Here’s where to browse the full archives of this newsletter.