November: Bare, cold, dark … and beautiful

Frontenac State Park Association newsletter

November 2024 (Vol. 2, No. 11)

Questions, comments, compliments, complaints, contributions? Newsletter editor Pamela Miller is at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com.

November: Bare, cold, dark … and beautiful

Is it just us, or has time sped up lately? Wasn’t it just May? Or July? Then, suddenly, September skidded in, and now November is hurling itself at our windows, an unexpected and not entirely welcome guest.

November! That little election you may have heard about is finally at hand, and we’re almost out of those delectable, diminutive Almond Joy bars the kids rejected on Halloween. Fall leaves have faded and fallen. Trees are bald and bare, their branches spectral, almost skeletal, against the early evening dusk. Oak leaves rattle in the wind. Frost is frequent, and surely snowfall is just around the corner.

Part of why November has taken us by surprise is that this year’s weather has been so, well, whacko. Consider: A winter with little snow. A spring of heavy rain. A summer of floods. A fall of warmth, wind and serious drought. Where are we? What time is it? Are we trapped in a weird parallel universe?

But! We’re actually here to celebrate November, a surprisingly excellent month in which to visit Frontenac State Park. Suddenly, on almost every trail, the fallback of foliage reveals rarely seen vistas. The chill in the air eases as you pick up your hiking pace. Animal tracks appear in the frost coating the leaf mat or in sparse new snowfall, offering clues to goings-on you’d never detect in other seasons. There are no crowds. And while many other public lands teem with hunters and can be nerve-racking to hike amid gunshots, the park is all yours, Mabel (except for Nov. 23-24, when it will be closed to the public for a deer hunt; read on for details).

Your Frontenac State Park Association sponsors fewer activities in November, focusing primarily on its quarterly meeting, at which next year’s activities are planned. But there is still a thing or two going on. From our calendar to yours:

November 2024

Saturday, Nov. 9, 10 a.m. to noon: Sand Point Trail bird walk. Meet at the Sand Point parking lot at the intersection of Hwy. 61 and Goodhue County Rd. 2 by 10 a.m. Walk through the riparian forest and along the beach to Sand Point. We’ll look for migrating waterfowl as well as resident birds of the forest, gulls, pelicans and raptors. Bring binoculars. The trail is well maintained and flat, although it can be muddy following rain. The full loop is about 2 miles long, but you can head out whenever you need to. Event is free, and there’s no need to register. Questions? Email janetmalotky@gmail.com.

Thursday, Nov. 21: FSPA’s quarterly meeting at the park’s main picnic shelter. This is one no-nonsense and sometimes lengthy meeting, although, yeah, we’ll have treats. We’ll plan our priorities, agenda and activities for 2025. Interested in joining the FSPA? This is a good opportunity to learn about what we do and meet some of our awesome members. Also, if you’re thinking about joining, we will be slamming you with love and treats!

Saturday and Sunday, Nov. 24-25: The park will be closed to all except for registered deer hunters. Explains park manager Jake Gaster: “We have fantastic deer habitat, and in the absence of natural predators, without a hunt, the deer population would grow to unsustainable levels, which would be harmful to natural communities in the park as well as the deer population itself. We will welcome around 60 hunters. They can set up their blinds/stands no earlier than Saturday, Nov. 16. The bag limit for the hunt is a maximum of three deer per hunter, with a maximum of one buck. Hunters must follow all standard hunting regulations, in addition to a few others specific to the park hunt (for example, only nontoxic ammo can be used, and no driving activities are allowed on Saturday). All blinds and stands must be removed from the park no later than Monday, Nov. 25. If a wounded deer ends up on private property, the hunter must request permission from the landowner to retrieve it before accessing the property [Jake or the game warden can help them contact the landowner].”

Friday, Nov. 29: Free day at state parks; no vehicle permit required for entry. The FSPA will have a welcome table at the main picnic shelter from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Treats are likely. (Let’s just say, treats and the FSPA go together like chocolate, and, uh, other chocolate.)

Book note: A celebration of nature at night

By Pamela Miller, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

When darkness drops dramatically in November, many among us wince, and do not welcome it. Some are even afraid of the dark.

No surprise – in our cultures, art and literature, even in our Netflix shows (your newsletter editor admits that “Lost” is a secret pleasure), darkness stands for the unknown at best, evil at worst. We are repelled by the dark arts, dark shadows, the dark ages, the darkness on the edge of town, princes of darkness, darkness visible (the term poet John Milton used to describe Satan, who sounds like nothing so much as a symbol of clinical depression in “Paradise Lost”).

But what if we thought differently about the night?

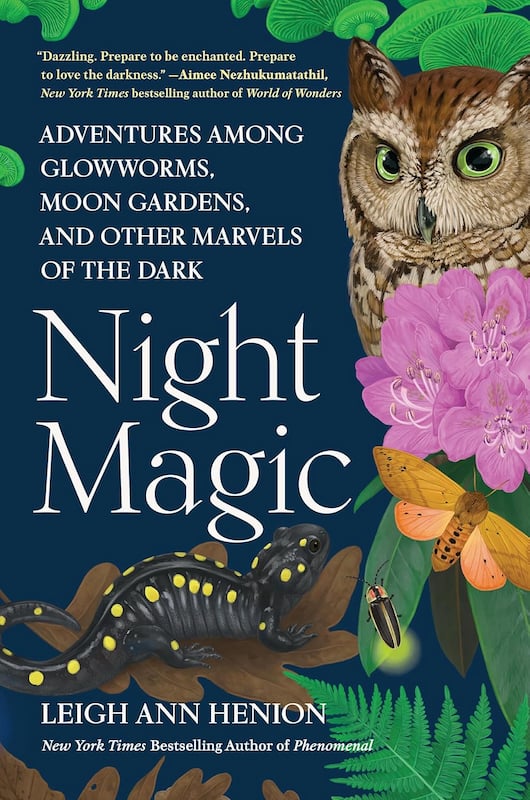

Your newsletter editor recently had the privilege to review “Night Magic” by nature writer Leigh Ann Henion for the Minnesota Star Tribune (gift link). This book, which seeks to break the spell of the dark, “is a revelation, a series of captivating field trips illuminating life in the wild at night,” I wrote. “Under the moon and stars, owls hoot and hunt; bats swoop at mosquitoes; glowing salamanders scurry; bioluminescent fungi, moths, fireflies and glowworms put on astounding shows; gardens creep up under the moon, and we humans lift our weary eyes to the stars, then rest and heal. At night, all the light we cannot see by day and by training emerges, and suddenly, after allowing our eyes and senses to adjust to the dark, we see glorious, beautiful night sights.”

And so, Frontenac State Park pals, here’s an idea. As November grows ever darker, how about we occasionally bundle up, pop on a headlamp, and walk a park trail after dusk? Needless to say, avoid the bluffside trails, lest you trip on a tree root and tumble hundreds of feet down – oh, never mind. But on a gentle prairie trail (or along any gravel road in the rural areas that surround the park), you can safely gaze up at the stars (perhaps even the aurora borealis) and listen for the mind-soothing sounds of the night, from night-migrating birds, to late-season insects, to barred owls wondering who cooks for you, to the intricate choruses of coyotes, to the wind rustling through dry prairie grasses.

Darkness need not be our enemy, or something to merely endure. Here’s to a quiet, peaceful, beautiful, dark November!

The insect named for a tree: Boxelders are bugging us

By Pamela Miller, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

For the past few weeks, those of us who live near or camp in Frontenac State Park territory have been cussing out an onslaught of boxelder bugs. These black-and-red insects hold messy conventions on the sunny sides of our houses, garages, shed, cars, outhouses, tents and RVs, swarm the south-facing sides of big trees (not just boxelder trees) and, along with invasive Asian lady beetles (don’t get us started on those buggers) take up annoying residence in our sunny kitchens, bedrooms and bathrooms.

Why, the other day your newsletter editor found two boxelder bugs swimming in her trusty mug of (highly affordable) red wine. Mon dieu!

This annual phenomenon seems even worse this year. What’s going on?

The boxelder bug (Boisea trivittata) is named for the tree it depends upon. The native boxelder tree (Acer negundo), a fast-spreading cousin to the maple tree, is found across most of Minnesota. According to the University of Minnesota Extension Service, it thrives in floodplains and along rivers and streams, and quickly spreads along fence lines and in abandoned fields. It’s not particularly showy, so it’s not in high demand for yards.

We humans may not love the boxelder tree, but boxelder bugs do. In midsummer, they swarm female boxelder trees, laying eggs on their bark, branches and leaves.

Why? Boxelder seeds are their main source of food. But they also eat the seeds and sap of maples, and swarm their bark, too.

Here’s the thing: Boxelder bug swarms occur most often in hot, dry summers, followed by warm springs. Sound familiar? Yep, that’s why you’ve seen so many in the past few years.

The good news is, both trees and bugs are native to our region, and their proliferation or lack thereof is all part of a natural cycle, though of course, if hot, dry summers become more frequent, they, too, will be more frequent.

And although boxelder bugs are annoying and messy, they’re harmless. Once winter arrives in earnest, you’ll see far fewer, although that doesn’t mean they aren’t slumbering somewhere below your house or in its siding to wait for a warm spring.

Says U Extension: “By spring, all the surviving boxelder bugs that overwintered inside buildings become active. They try to move outdoors, but many remain trapped inside. They do not reproduce in homes. All the boxelder bugs seen inside during winter and spring entered buildings the previous fall.”

Pesticides aren’t particularly helpful against boxelder bugs. Just get yourself a good vacuum cleaner and a dose of patience – and remember, November’s increasing cold will mean they’ll soon disappear.

For a while, anyway.

Bird note: A swan dive

By Janet Malotky, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

Swans are avian stars any time of the year. Their size, grace and gleaming white feathers make them amazing both flying and floating. They particularly shine in November.

This is because, in addition to pairs of Trumpeter Swans dotting the ponds in our countryside, we also have the good fortune to see strands of Tundra Swans winging their way along the Mississippi flyway toward their wintering grounds in and around Chesapeake Bay. Along the way, they rest by the thousands in the quieter backwaters of the Mississippi, a delight to witness.

Two kinds of swans can reliably be seen in our area – the Trumpeters who arrive in spring from states just to our south to raise their young throughout Minnesota and farther north, and the Tundras who pass through on their way to and from their nesting grounds in the Arctic tundra.

Very occasionally, a third type, the Mute Swan, can be spotted among other swans, though it is rare in our area. Mute Swans can be easily distinguished from the other two by orange bills with a black knob at the base, their curvaceous neck posture, and their sometimes partly raised wings while swimming.

But distinguishing the other two from each other by sight is a challenge. The Trumpeter is larger than the Tundra, but size is tough to judge unless they’re side-by-side in the water – and the way they can scrunch and stretch just adds to that confusion. Both have black bills, and the black reaches back to meet the eyes. This black area on Tundra swans narrows a bit just in front of the eye and they can, but don’t always, have a small yellow spot at that point. Trumpeter swans never have the yellow spot.

There are a couple other even more subtle clues, but c’mon. When they’re flying? Forget about it.

Fortunately, for those who like to know what they’re looking at, there are other identification clues. First, the two types of swans have different behaviors. Tundras can be seen here only during migration in the spring and (especially) the fall, whereas Trumpeters arrive in the spring, with many staying all summer before leaving in the fall. Tundras will generally be in large groups. Trumpeters will be in swimming pairs on countryside ponds, often with their two to nine gray cygnets (chicks).

But the most reliable distinguishing feature between Tundras and Trumpeters is sound. Both have loud voices. But Tundra’s voices are higher-pitched than Trumpeter’s, and Tundras are not shy about talking. A flock of Tundras flying overhead is described by Sibley’s as sounding like the “baying of hounds.”

In large groups, dabbling in a bay, Tundras are constantly chattering, like the largest, most raucous family reunion ever. They make slightly quieter sounds too, less frenetic-sounding than their group talk.

Follow this link to hear recordings of Tundra Swans. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Tundra_Swan/sounds

Trumpeter Swans are less talkative. Their voices are lower and more honky, a bit like Canada Geese. Like Tundras, they talk when flying and when floating, but they lack the insistent chattiness of Tundras. Even their pair alarm calls sound subdued.

Follow this link to hear recordings of Trumpeter Swans. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Trumpeter_Swan/sounds

So where can you see swans in Frontenac State Park? In November and December, they fly south along the Mississippi River. If you hear them overhead but can’t find them, scan high in the sky for their southbound “V” formations. Occasionally swans stop to rest in the bays on either side of Sand Point. Trumpeters might take a turn in Pleasant Valley Lakelet, though I’ve yet to see them choose that pond for breeding. Swans have also been seen off the beaches in Old Frontenac.

To see them by the thousands, though, you’ll need to venture farther south along the river. People flock to the Highway 61 overlook just south of Brownsville, Minn., every early to mid-November to experience the flocks of migrating Tundras, dabbling with the many other waterfowl taking a migration breather there. An Upper Mississippi River National Fish and Wildlife Refuge naturalist will be stationed there each weekend from Nov. 2 to 17, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., with scopes and information to help enhance your visit.

Find more information tracking bird types and numbers along the river at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/upper-mississippi-river. Happy hooting and honking!

Notes from the field: Night time

By Steve Dietz, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

Naturally, we all love biodiversity and recognize that everything is connected to everything else. Nevertheless, most of us have particular passions: birds, plants, fungi, butterflies, bees, even insects. I love a clear night sky with the Milky Way leading my thoughts like a yellow brick road to Oz as much as the next human, but in truth, astro-stuff has never really been my thing.

For some reason, however, I can’t get the image in the photo above out of my head.

At first I thought its tidal pull on my thoughts was the “fact” that it wouldn’t re-appear for another 80,000 years. Sure, I was unlikely to see it again, but what about my great great great great …[repeat 2,600 times] grandchildren? What might they think when they saw it?

80,000 years ago, Earth was in the midst of an Ice Age, known as the Last Glacial Maximum. Modern humans were still evolving and migrating out of Africa. They encountered and interacted with other human species like Neanderthals and Denisovans. I wondered -- will the progeny of Earth in over 2,500 generations have evolved into something other than Homo sapiens? This train of thought wasn’t derailed when I discovered that astronomers had refined the calculation of the comet’s path to slingshot out of the solar system, never to return. To our current knowledge, no one will ever see it again, in person.

In a former life, I organized (with many other people) an outdoor arts festival that ran from sunset to sunrise. All night. Over the years, there were hundreds of projects that created joy and instigated deep thoughts, but there was something about the night itself that made it extra special. Night is a time of dreaming; imagining nether worlds, half-worlds, past worlds, future worlds. The limited visual cues in darkness heighten our imagination and our other senses.

At Frontenac State Park, the whispering night air can almost be tasted as it flows over the tall prairie grasses; the sounds of owls and coyotes under a dark sky strike a primordial cord that even the best podcast can’t match. We find ourselves thinking about our lives, our families and neighbors. Our institutions.

What will become of us in 80,000 years, whether or not there is a Comet A3 to observe us?

A captivating nature blog to bookmark

We’re delighted to report that interpretive naturalist Bruce Ause, retired director of Red Wing’s Environmental Learning Center and an FSPA member, has rebooted the hyperlocal nature blog he set aside during the COVID years. We’ll miss the beautiful photos that Bruce regularly contributes to this newsletter, but you can now find them in his blog.

Bruce’s recent posts include stories about a Wacouta prairie restoration, the biology of black squirrels, and dragonfly migration. Check it out (and when there, you can sign up for emails about new posts): https://wacoutanaturenotes.wixsite.com/mysite

Coming in December: Winter in the park

Snow or no? We vote for snow! In December’s newsletter, we’ll celebrate snow-dependent winter activities in the park. So shake out the snowshoes and wax your skis. We’re betting on a winter wonderland.

Poem of the month

“NOVEMBER SKIES”

By John Freeman (British; 1880-1929)

Than these November skies

Is no sky lovelier. The clouds are deep;

Into their gray the subtle spies

Of color creep,

Changing that high austerity to delight,

Till even the leaden interfolds are bright.

And, where the cloud breaks, faint far azure peers

Ere a thin flushing cloud again

Shuts up that loveliness, or shares.

The huge great clouds move slowly, gently, as

Reluctant the quick sun should shine in vain,

Holding in bright caprice their rain.

And when of colors none,

Not rose, nor amber, nor the scarce late green,

Is truly seen –

In all the myriad gray,

In silver height and dusky deep, remain

The loveliest,

Faint purple flushes of the unvanquished sun.

Interested in joining the FSPA?

We’d be honored to have your support. Dues are $25 per year for an individual, $35 for dual/family membership. Here’s a link with signup information.

A reminder that joining us occasionally to help with volunteer efforts is awesome too, even if you’re not a member. The FSPA’s goal is simply to share our love of Frontenac State Park with as many people as possible.

To sign up to regularly receive this free and gloriously spam-free monthly newsletter, click on “Subscribe” below. Feel free to send questions or comments to your newsletter editor at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com. Questions about the FSPA? You can reach hard-working FSPA chair Steve Dietz at stevedietz@duck.com.

Handy links for more information and education

Frontenac State Park website

Frontenac State Park Association website

If you take pictures in the park, tag us on Instagram

Frontenac State Park bird checklist

Frontenac State Park on iNaturalist

Parks & Trails Council

Website for our township, Florence Township

Minnesota Master Naturalist program

Red Wing Environmental Learning Center

Lake City Environmental Learning Program on FB

Visit Lake City

Frontenac State Park staff

Jake Gaster, park manager; Amy Jay, assistant park manager; Amy Poss, lead field worker

Parting shots

Thank you, readers and park visitors!

This is Volume 2, No. 11 of the Frontenac State Park Association newsletter, which was launched in April 2023.

Here’s where to browse the full archives of this newsletter.