December: What kind of winter will this be?

Frontenac State Park Association newsletter

December 2025 (Vol. 3, No. 12)

Comments, contributions, compliments, complaints? Reach your newsletter editor at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com.

December: What kind of winter will this be?

For the third year in a row, we’re having trouble deciding what photos to use for our December newsletter. The ones with lots of snow? Or those of a barer, browner landscape? In recent years, snow has been far from a given in our region. We’re hoping Dec. 1 will find us with some on the ground, even enough for Frontenac State Park to be able to groom its cross-country ski trails. But who knows?

Either way, December is a month to treasure, with winter in earnest arriving along with its cultural messages of hope. We hope you have a wonderful one!

Upcoming park events

Saturday, Dec. 6, 9-11 a.m.: Guided Prairie Loop bird walk with Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer Steve Dietz. Meet at the Frontenac State Park ranger station parking lot. We’ll take a short prairie loop to look for year-round residents such as Pileated Woodpeckers, identify some over-wintering sparrows, such as White-throated Sparrows and Eastern Bluebirds, and perhaps see some late-migrating waterfowl overhead. Questions? Email janetmalotky@gmail.com.

Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026: Our annual First Day hike. What better way to welcome the new year than with a quiet walk in the park? Stop by the main picnic shelter between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. for greets and treats.

Saturday, Jan. 31, 2026, 6-8 p.m.: Our annual Candlenight walk/ski/snowshoe. Come enjoy the nearly full moon, luminaries in the woods, bonfires and treats at the main picnic shelter, courtesy of the FSPA.

FSPA prepares for a new year

The Frontenac State Park Association held its quarterly (and annual) meeting in November to elect officers (stars, all), update its bylaws (bulletproof), review its budget (healthy) and catch up on all the news from park managers Jake Gaster and Amy Jay. Our 2026 officers: Steve Dietz, chair; Nathan Oppedahl, vice-chair; Barb Partington, secretary, and Deb Jeske, treasurer. We also confirmed our 2026 membership fees. Please send in your membership renewals. More information at the bottom of this newsletter.

Meanwhile, Jake’s park updates:

Park attendance so far this year (January through October) is 187,570, around average for the past few years but still ahead of what attendance at this point looked like pre-COVID (back then, it was usually 130,000 to 140,000). We’ve had the highest number of campers ever recorded in the park, with 19,681 camping overnight from January to October, already more than any full year prior.

Our Nov. 22-23 deer hunt went off without a hitch; 30 deer were taken by hunters. That’s on the low end of what we were hoping for, but given that temperatures were in the 50s, it’s not too surprising, as the deer weren’t moving around much.

Our fall burn season was a success. More than 220 acres were burned. We were able to accomplish most of the burns we were hoping to get in (with the notable exception of the Prairie Loop, which we’ll hit in the spring). With snow just arrived, it’s safe to say our burn season is officially over for the year.

The park has served about 1,500 visitors with interpretive programs, largely thanks to our FSPA volunteers. That’s slightly down from 2024, which is misleading because we had more programs and visitors attending them this year. The reduction is solely due to the high attendance at 2024’s Candlelight Event, when temperatures were in the balmy 40s.

The beaver dam controlling water levels in the Frontenac pond burst several weeks ago, and the water level has dropped sharply. The beavers are hard at work clearing trees along the pond in efforts to rebuild, but so far we’ve seen no progress on a new dam (though a new lodge has sprung up along the Prairie Loop trail that runs along the pond’s edge).

Gut check: The surprising importance of offal

By Pamela Miller

Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

The holidays can get awfully sweet. As your newsletter editor’s Southern-born father used to drawl, “You could get the sugar diabetes easy this time of year.” So let’s get this party started with something that decidedly isn’t gauzy — let’s talk about offal.

There’s a surprising lot to learn about our natural world from monitoring gut piles after November’s deer hunt. Biologists and naturalists, assisted by citizen volunteers, do so every year, including in Frontenac State Park. To learn more, we turned to Grace Milanowski, who has the awesome job title of program coordinator for the Offal Wildlife Watching Project, part of the Department of Agricultural and Natural Resource Systems of the University of Minnesota Extension Service.

Here’s what Grace had to share.

Q: Thanks for helping us out on this fascinating topic, Grace. Tell us a little about yourself and how you got involved in this area of research.

A: I have a background in environmental science and avian research, with a lot of volunteer management and nonprofit roles in between. I found this job posting and was drawn to the combination of research, working with volunteers and researching dead stuff! It's an unusual project, but I love that I get to be curious in my role all the time.

Participatory science lets us investigate questions that participants propose and lets me share in the excitement with what people are discovering as they help us collect data.

Q: What is offal? Many people will wince at the image -- but clearly it's valuable to research. Why is it important?

A: Offal refers to the discarded parts of a butchered animal, so the parts that hunters don't usually take home with them to cook and eat. While it's not very appetizing to humans, it's a really nutritious food source for scavengers, especially when food is scarce in the winter.

Typically, about 150,000 deer are hunted each year in Minnesota alone, which equates to about 3 million pounds of offal left on the landscape that scavengers enthusiastically take advantage of. Our species list of offal visitors is now over 62 different species.

This hunter-provided offal wouldn't be available at this time of year if it weren't for managed deer hunting seasons. Deer are typically in peak physical shape in fall/early winter and less likely to die naturally, so we're interested in how scavengers use this pulse of food source available at this time of year.

The topic also hasn't been studied much, so we're doing analysis like: How do the scavengers visiting and eating offal differ in Minnesota’s various biomes? Who is arriving first? How long do gut piles persist on the landscape before they're completely consumed?

We aren't directly studying chronic wasting disease, but we know other researchers are interested in our findings as it may relate to disease transmission.

Q: What is the Minnesota Offal Wildlife Watching Project?

A: The Offal Wildlife Watching project is a research and participatory science project with University of Minnesota Extension. We receive funding from the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources. We’re in our seventh year of data collection and it’s very exciting to see it growing in popularity and participation each year.

This year so far, I have mailed out 175 cameras to hunters throughout the state. [This was before this fall’s hunting season began.] We ask hunters to help us collect data by setting up a remote trail camera on their gut pile immediately after they field dress their deer. Hunters can use their own cameras or we have camera projects to loan out. The cameras stay up for a month to collect images of all scavenger visitors to the offal.

We post all our project photos on a participatory science online platform, Zooniverse, where volunteers from all over the world help us identify and quantify what’s happening in the photos. We’re a small research team and utilizing Zooniverse is the only way we could analyze the hundreds of thousands of photos we collect each season. Anyone is welcome to help us on Zooniverse as well as to become a hunter participant in our research.

Q: Is Frontenac State Park involved in this project?

A: Yes! It has been involved for a few years, setting up cameras during its yearly deer hunt [which took place Nov. 22-23 this year]. Here is a compilation of gut pile photos from the park’s 2024 hunting season.

Q: How can citizens participate?

A: Hunters can register on our website at offal.umn.edu. We ask that they sign up before they hunt to let us know what kind of hunting they’re doing and if they need a camera mailed to them. There is another brief data form to fill out once they kill a deer and set up their camera, and when they retrieve their camera. If hunters borrow a camera kit from us, they can mail the entire kit back and I can upload photos to an online shared folder they can view. If hunters use their own cameras, we send them a link to a Google Drive folder where they can upload photos for us to use.

Anyone with internet access can join us to help analyze and identify project photos on Zooniverse. Our project page walks you through a few questions for each photo so we can turn an image into quantitative data to analyze. Zooniverse also has discussion boards where participants can ask us researchers questions or talk to fellow participants about unusual or exciting findings. [By the way, readers, helping with this project is an excellent way to collect Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer hours.]

Q: Can you share some especially interesting findings, stories or anecdotes from your research? Have there been any especially surprising findings?

A: People are usually surprised to hear that the majority of offal eaters are birds. About ⅔ of the species we’ve documented so far are different birds. I was surprised that in Year 6 of data collection last year, we added 10 new species to our list. It just goes to show that there are plenty of scavengers taking advantage of a free meal; we just need more cameras out to document it!

Other surprises have been animals that we think of as exclusive herbivores like rabbits eating offal. We even have documentation of deer eating offal, and most every camera collects images of deer coming in close to check out a gut pile. That raises questions about possible avenues of disease transmission. But when animals come across a nutrient- and protein-rich free meal, it’s hard to pass it up when other food may be scarce.

Thanks to one of our hunter participants alerting us to some interesting behavior of owls at their gut pile, we published a paper on barred owls using offal as opportunistic hunting grounds for rodents. We’re not sure if owls arrive at offal as a scavenger and then find live rodents to hunt or if they know offal attracts rodents to easily grab a fresh meal, but it was previously undocumented behavior that warranted a new publication. We also have documentation of bobcats exhibiting the same hunting behavior.

People interested in our work are welcome to sign up for the newsletter we send out periodically (find a link at offal.umn.edu) and stay tuned to our website, where I post project results as they come out.

Q: Thanks so much, Grace! By the way, we're guessing you hear a lot of nonsense, bad jokes and puns about researching offal. Any you'd like to share?

A: One has to have a sense of humor when studying guts — we love to hear the puns, please send them our way. Offal isn’t always awful!

Bird note: An invasion afoot … er, a-wing

By Janet Malotky, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

If you’ve been hearing a persistent nasal “yank yank yank” in the trees around here since September or so, you are not alone. The sound belongs to a plump little bundle of bounce known as the Red-breasted Nuthatch. This bird displays the same amazing antigravity behavior as our more common resident, the White-breasted Nuthatch, scooting up, down and sideways in trees, plus hanging upside down. They don’t even use their tails to brace themselves like woodpeckers do.

How do they do it?

Red-breasted Nuthatches are smaller than their white-breasted cousins, with even less visible necks, which makes them look especially adorable, like eggs with legs. Though their name says red, they have orangish breasts, which are brighter on males. What really sets them apart from the White-breasted Nuthatch is their facial pattern. They sport a thick black line through the eye that stretches from beak to back. This is topped by a thick white “eyebrow” and a thin crown stripe, black for males and gray for females. The White-breasted Nuthatch has a plain white face and a wide black stripe on crown and nape.

We started hearing a Red-breasted Nuthatch on our back hill this Sept. 1. Then, in mid-November, a little fellow came to our feeder to steal a peanut. As of this writing, the bird has stuck around.

Red-breasted Nuthatches are permanent residents of much of Canada and the western United States. They can be seen in the rest of the United States out of breeding season. Minnesota is divided diagonally in half, with the northeast hosting permanent residents and the southwest the non-breeders. Frontenac is on the dividing line between the two. But just because they can live here doesn’t mean they do. We occasionally spot them up on the Pine Loop Trail, but I usually feel lucky to see or hear one once or twice a year. We’ve certainly never had one at our feeder!

Lots of other birders are reporting unusual sightings as well. So what’s going on?

It’s an irruption year! Irruption (pronounced like eruption) is a disruption in the typical migratory behavior of a bird population, usually caused by a shortage of food such as nuts, seeds and/or berries on their home turf. According to the Winter Finch Forecast (yes, there is such a thing), in this case, the boreal forest cone crop is poor this year, so these northern birds have been flying south since August looking for food. Though not so lucky for them, we might get to enjoy their visits all winter long.

If the word “irruption” suggests rushing waves of birds, let me temper that expectation. Red-breasted Nuthatches will not be bouncing around like popcorn in the trees. Expect to see some of the little dears in our area, where previously you may have seen one or none.

Other birds are subject to irruption years as well. For example, in Minnesota we can experience irruptions of Pine and Evening Grosbeaks, Red and White-winged Crossbills, Bohemian Waxwings, Redpolls, Snowy Owls, Purple Finches and Pine Siskins, though most of those dip only as far south as northern Minnesota. Last winter there was an irruption of Great-gray and Boreal Owls along the North Shore of Lake Superior due to fluctuations in the rodent population on their home turf. This spurred a flurry of birding tourism that resulted in an unusually high number of vehicle/owl collisions. Sigh…

Friends, let’s be considerate and gentle with the creatures in our midst. If you’d like to provide food for Red-breasted Nuthatches, they enjoy peanuts, suet and black oil sunflower seeds.

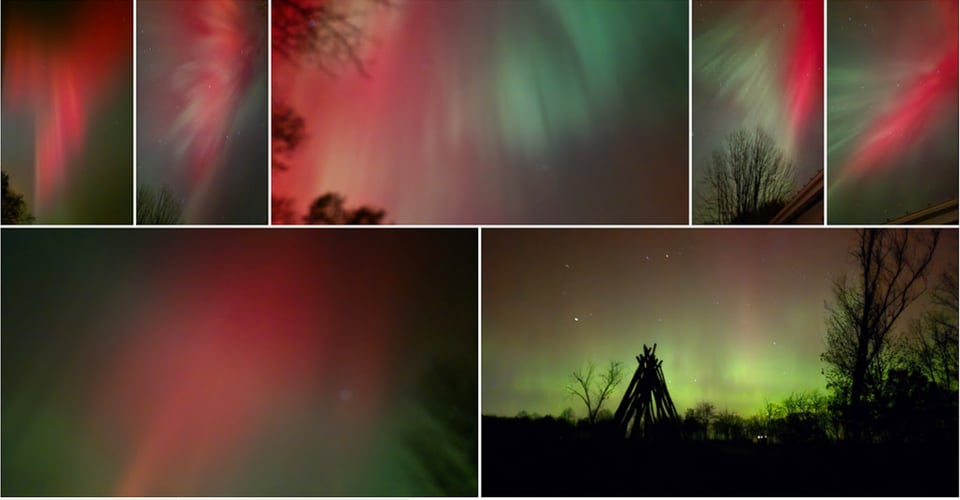

Notes from the field: The wonders of the aurora

By Steve Dietz, Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer

Last month, the Northern Lights were so spectacular and so widely seen that it was as much cultural event as natural phenomenon. Like a good play or a remarkable sporting contest (World Series anyone?), conversations the following days inevitably led beyond “Did you see?” to questions about how and why and even “What does it mean?”

If you want to dive deep into Alfven waves and Birkland currents, there are many in-depth explanations from NASA to Space.com to the citizen science site Aurorasaris and always Wikipedia. Here are some stabs at answers and some factoids almost as remarkable as the lights themselves.

First, some nomenclature. Northern Lights refers to a phenomenon more broadly known as an example of an aurora, a term first used by Galileo — yes, that Galileo — in 1619. Thirty years later, the term aurora borealis — the northern lights — was used to describe an occurrence in France, and in 1770 Capt. James Cook saw the aurora australis in the southern hemisphere. Since then, auroras have also been seen on other planets and even on comets and brown dwarfs!

Of course, keep in mind that people experienced auroras long before Western scientists named them. The earliest datable record of an aurora was recorded in the Bamboo Annals, but there may be images of auroras in cave paintings dating back 30,000 years. A written Chinese legend referred to one in 2600 BCE, and auroras are part of the oral traditions of people living in polar regions around the world.

What causes an (earthly) aurora? Broadly speaking, this is an interaction between solar winds and the Earth’s magnetosphere. To understand the general interaction, think of a neon sign. When you flip the switch to turn it on, electrodes at either end of the sign pass an electric current through the enclosed gas and “excite” the atoms, many of which gain a higher energy state, like climbing a rung on a ladder. To “climb down” from their excited state, atoms often release energy by emitting a photon or light. It’s an imperfect analogy, but think of the solar wind as a current that excites atoms in Earth’s atmosphere. While the magnetosphere deflects much of this energy, during periods of increased solar activity it manages to excite atoms in the atmosphere to such an extent, they emit light to discharge that excess energy — an aurora.

Why are there different colors? Essentially, different gases in the atmosphere emit different colors when they are excited, like a spectral fingerprint. If you see a red aurora, you know that it is from the oxygen in the atmosphere 120 miles above the Earth.

Keeping with our electric neon sign analogy, we can say that the color tells us the voltage of an aurora. During very large magnetic storms it is common to have very bright red auroral displays. Green is usually the main color of the northern lights, and blue and purple emissions typically appear at the lower edges of aurora "curtains," generally only at the highest levels of solar activity.

The Space Weather Prediction Center issued a highly uncommon "severe" geomagnetic storm watch for Nov. 11 and 12, which helps explain the prevalence of red lights on those nights.

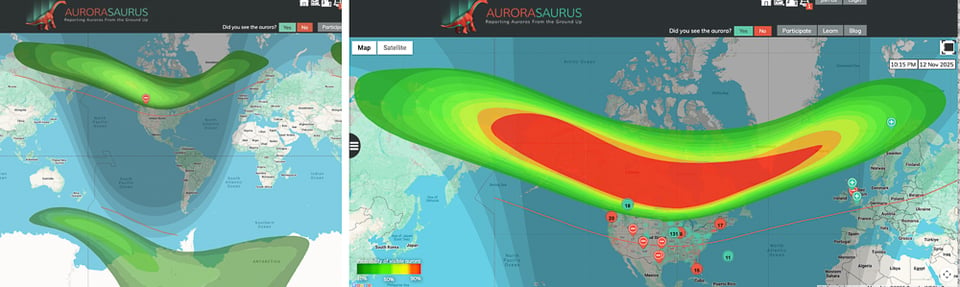

Why do auroras appear in lower latitudes? The aurora is present continuously every day in an oval shape around Earth’s northern and southern magnetic poles, although not necessarily strongly enough to be seen with the naked eye.

To use another imperfect analogy, just as high pressure systems can shift the jet stream farther south, strong solar winds can shift the northern lights farther south and make them more visible. In the diagrams below, the color indicates the likelihood that an aurora is visible and the red line indicates the range where an aurora is predicted to be visible.

Besides awe, what are the effects of auroras? Auroras do reflect increased electrical activity in the atmosphere. During a geomagnetic storm in 1989, electrical currents melted transformers in New Jersey and wiped out power through much of Quebec, leaving 6 million people in the dark. In 1859, during the Carrington Event, the largest geomagnetic storm in recorded history visible from the poles to the tropics, almost unbelievably, some telegraph lines seem to have been of the appropriate length and orientation to produce a sufficient geomagnetically induced current to allow for continued communication between telegraph operators in Boston and Portland, Maine, for two hours with power supplies switched off!

Many animals, including birds, bees, and some whales and dolphins, can detect the Earth’s magnetic field lines and use their orientation to navigate. While it’s solar storm activity, not the auroras themselves, that messes up the magnetic field, physicist Klaus Heinrich Vanselow’s studies estimate that solar activity could affect up to 20% of strandings of sperm whales. It also may affect nocturnal bird migration.

When is the best time to see auroras? Generally, the hours around midnight are best, and historically geomagnetic activity is more active around the equinoxes and during March. The best way to find out, however, besides friends texting you to wake up and go outside, is to monitor aurora prediction sites such as NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, Aurorasaurus, where you can (and should) report your sightings, the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and SpaceWeather.com, among other resources.

Final question: Why do the lights look better in my camera? This is primarily a question of biology and optical technology. Human eyes have rods and cones. About 95% of the photoreceptors in our eyes are rods, which help us see in dim places, but they can’t see colors at all. At night, we’re primarily using our rods. The result is like wearing dark sunglasses to watch a movie. Colors appear washed out and muted. Similarly, under a starry sky, the vibrant hues of the aurora are present but often too dim for your eyes to see clearly. On the flip side, according to Douglas Goodwin, camera technology has advanced to the point where even your smartphone, especially in a night photography setting, can see better than you. But don’t worry, your camera can’t enjoy the results as much as you do.

Mushroom of the month: The festive fly agaric

The beauty around us: Notes from Bruce Ause

Interpretive naturalist and treasured friend of the park Bruce Ause keeps a wonderful nature blog. Most recently, we enjoyed his ruminations on woodpeckers, northern lights, goldenrod galls and all manner of other things he has observed of late. Check it out.

Poem(s) of the month

“Epirrhema”

By Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German; 1749-1832)

Translated from the German by Michael Hamburger

Always in observing nature

Look at one and every creature;

Nothing’s outside that’s not within,

For nature has no heart or skin

All at once that way you’ll see

The sacred open mystery.

True seeming is the joy it gives,

The joy of serious playing;

No thing is single, if it lives,

But multiple its being.

“Year’s End”

By Matsuo Basho (Japanese Edo period poet; 1644-1694)

Year’s end,

all corners

of this floating world, swept.

Interested in joining the FSPA?

If you are a member, thank you! You help us pursue our mission of supporting this treasured park in myriad ways. Now is the time to renew.

If you’d like to join us, we’d be honored to have your support, especially as we build our 2026 membership list – remember to renew if you’re already a member! Dues are $25 per year for an individual, $35 for household membership. Here’s a link with signup information.

A reminder that joining us occasionally to help with volunteer efforts is awesome too, even if you’re not a member. The FSPA’s goals are to support Frontenac State Park activities and share our love of this beautiful park with as many people as possible.

To sign up to regularly receive this free, spam-free monthly newsletter, click on “Subscribe” below. Feel free to send questions or comments to your newsletter editor at pamelamarianmiller@gmail.com. Questions about the FSPA? You can reach FSPA president Steve Dietz at stevedietz@duck.com.

Handy links for more information and education

Frontenac State Park

Frontenac State Park Association

If you take pictures in the park, tag us on Instagram

Frontenac State Park bird checklist

Frontenac State Park on iNaturalist

Parks & Trails Council of Minnesota

Website for our township, Florence Township

Minnesota Master Naturalist programs

Red Wing Environmental Learning Center

Lake City Environmental Learning Program on FB

Visit Lake City

Zumbro Valley Audubon Society

Bruce Ause’s Wacouta Nature Notes blog

Marge Loch-Wouters’ Hiking the Driftless Trails blog

Frontenac State Park staff

Jake Gaster, park manager; Amy Jay, assistant park manager; Amy Poss, lead field worker

Parting shots

Thank you, readers and park visitors!

This is Volume 3, No. 12 of the Frontenac State Park Association newsletter, which was launched in April 2023.

Here’s where to browse the full archives of this newsletter.