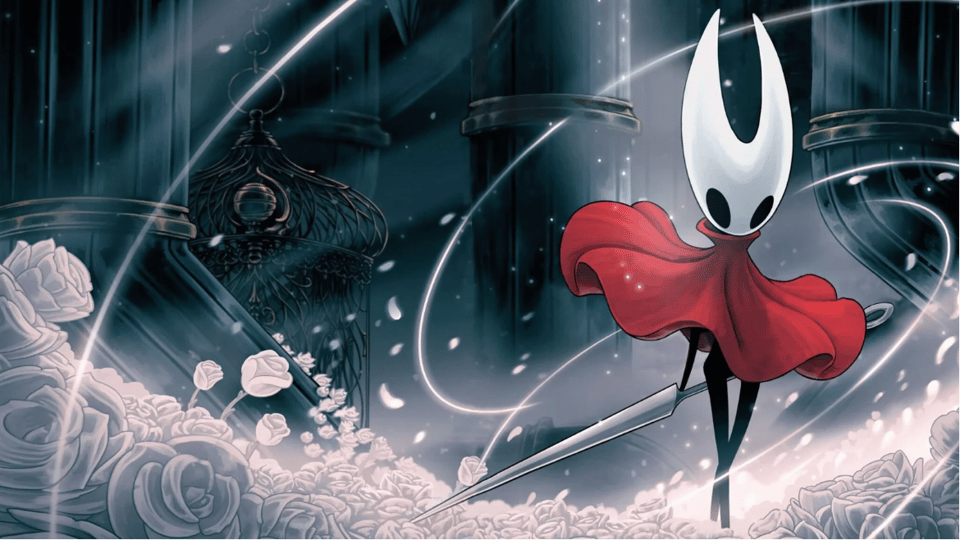

You Will Always Be Your Mother's Daughter - Silksong

Before I even begin, I want to say: this essay will include spoilers for all of Silksong, including the True Ending. If you want to play or experience the game for yourself, please pass this newsletter by. I hope you’ll come back, though, one day.

Hello hello. It’s been a while—summer ended, autumn is here, even though it’s still warm enough here to make me nervous for the future. Today I finished watching the VOD of Skurry’s playthrough of Silksong—because I haven’t even finished Hollowknight and I know I would find Silksong utterly punishing—and found myself sitting stunned, unable to do anything but watch. Afterwards, all I could think about was:

You are not chosen. You are not the saviour of this world.

You will always be your mother’s daughter.

Both Hollowknight and Silksong are stories about the decay of an existence long past its natural end—whether that be a kingdom long-since dead, a vast immortal being at the heart of the world, or a creature of silk in the form of a young girl. This is seen clearly in the design of both games, the decaying halls, the crumbling stone, the towns populated more by corpses than the few remaining bugs who haven’t succumbed to the slow creep of entropy. Silksong does not hide its themes—the entire area of Whiteward shouts about the foolish ego of the bugs who injected silk beneath their shells to extend their lives, now nothing more than bloated puppets of Grand Mother Silk. Anything that lives in Pharloom is not truly part of the life of the kingdom, but simply a last dying gasp of the kingdom. Nothing can evolve within its borders so long as the old world refuses to die. Death is an ending, yes, but perhaps a necessary one on the path to rebirth.

Hornet is only able to evolve away from the shadow of Hallownest—how many ages have passed, guarding those halls, always a child of the kingdom, Weaver, Wyrm? It is only through her time in Pharloom, away from the world that her parents shaped, that Hornet is able to grow beyond her childhood. Where in Hallownest, Hornet remained a child (‘The Gendered Child’, born of weaver and wyrm), in Pharloom she slowly grows beyond that label, to be recognized as herself. Shakra, who for much of the game calls her merely ‘child-wielding-needle’, upon Hornet joining her in remembrance of her dead mentor, finally calls her by her name. They have both reached the end of the path laid out for them by their mothers, and it is only in stepping away into the unknown that they are able to reach adulthood. Despite this, Hornet will always be a child of Hallownest, sentinel-protector, and just as Shakra chooses to use the weapons and skills her mother gave to her to protect the bugs of Pharloom, so too does Hornet use her own memories to save another world from the destruction her own mothers were unable to prevent. They each choose to carry on the work of the women who raised them, but it is as adults irrevocably touched by those women making that decision, not as children still trapped by their wills.

I say, then, that Hollowknight: Silksong is a story about mothers, about the women who raise us, teach us, who shape the world we know and send us out into it. Hornet, daughter of three women who gave everything for the future of Hallownest, and for her. Shakra, searching for the woman she would choose to call mother, knowing all the time that the only thing to be found at the end of the quest is a kind of closure. Lace, trapped by her mother’s silk just as surely as any of the lost bugs puppeted about the citadel. Silksong asks the question over and over again: who will you be?

Will you follow the path she laid out for you? Who will you be when you reach the end of that path, and have to step beyond it? What will you do when the world your mother built dies?

It is easy to talk about death as the passage to rebirth, as a necessary step in our lives. it is much harder to accept that grief and move not beyond it, but instead to use it as the driving force to take that first step. We see, throughout the game, but specifically during the Red Memory, that Hornet understood that her mother sacrificed herself for the good of the kingdom, yes, but more than that: for Hornet, herself. What else could she want but to see a better world made for her daughter—”that I may live to see a world better than our own”. Her mothers’—Herrah, Vespa, and finally The White Lady— wish became the defining evidence of their care for Hornet, and yet…as the White Lady herself says, “So much pain you must have passed to speak our hope so simply”.

The wish should be evidence enough, but still…in your memory, your mother’s face will always be the mask she donned for the good of the kingdom. You try to remember. “..A mother... before the mask... before I lay forever in duty...”

Lace, then—sentinel like Hornet, forever wandering the empty halls, feeling always the weight of her mother’s presence within the foundations of her world. A child forged not born, created for a purpose beyond simple existence. Lace is driven by the purpose—that she believes—she was made for, desperately trying to prove her worth as knight to her mother, and yet she believes herself to have been made imperfectly. “She spun us to fade... She spun us to break... Why us, sister... Why us?” Lace sees this perceived imperfection not as a mark of the transient nature of life, but as a failure to achieve the purpose for which she was made, a failure in her mother’s eyes and hence in her own. Compared to both Shakra and Hornet who have been forced to confront the mortality of their own mothers and so grown into adulthood through their own choices, Lace is noted to act as a child, despite her many years wandering Pharloom as her mother’s hands and fingers. In fitting herself into the role her mother made for her, in striving for perfection in her mother’s eyes, Lace is trapped in the role of child, without agency in her own future. It is this conflict then, the desperation to be worthwhile to her mother, her awareness of herself as a flawed being, that, combined with the arrival of Hornet—perfect, weaver and pale being, a child befitting the grandeur of Grand Mother Silk—brings forth Lace’s resentment.

“See me, your knight...

See me, your daughter...”

When Lace saves Hornet from Grand Mother Silk’s grasp, descending into the Abyss, Hornet assumes that the great struggle shaking Pharloom and threatening to destroy the kingdom is that of a mother protecting her daughter. Lace, however offers a different interpretation: that instead Grand Mother Silk can “thrash, and waste, and know her pathetic, broken child caused the mortal wound”. Later, we see that it is indeed Hornet who is right—Grand Mother Silk is using the last of her power to protect the sullied fragment of her daughter, but Lace is unable to see this final act of—indeed—love from her mother as she has so long viewed herself as nothing but a rag, valuable only so long as she is useful, the perfect child that she can never truly be. Lace’s ‘rebellion’ is not an act of vindication against her mother, but the final reflection of her perceived failure to follow the path her mother set for her. I do not believe it is a stretch to describe both Lace and her sibling Phantom as experiencing passive suicidal ideation linked to this perceived failure. At first Lace claims that in dragging her mother to the void she has won, but later adds “Join us in my drowning palace, and let oblivion swallow us all”. Note that Lace describes the Abyss as her drowning place—her own punishment, not merely that of her mother.

That after everything, every time Lace merely stood sentinel for her mother, that she herself is the final challenge of the game is perhaps one of the most brilliant moments of narrative game design I have seen in a long time. This is not a story about a kingdom, about a great and monstrous being. This is a story about one girl, desperate for her mother’s approval.

In the end, Lace’s defeat, her death, is what saves her. Grand Mother Silk gives Hornet the power to save herself, and Lace with her. It is the final gift of her mother that enables the journey, but it is Hornet—who has faced the same grief herself and become all the stronger for it—that carries Lace away from that dark place, away from the depths she threw herself into and back into the light.

The old world is dead, it is only from its death that you can learn to live your own life.

You will never know how much your mother loved you.

What I’m reading right now:

Back on that House of Leaves spiral, I can finally say I’ve made it through half of the book, not counting appendices, which I’ve also read most of so really I’m more than halfway through.

An album to listen to:

It would be easy to say ‘the Silksong OST’, but instead I must offer Atlas II, by Sleeping At Last. I listened through the album while writing this newsletter, and Sleeping At Last is one of those musicians who never fails to strike something deeper inside me than I anticipate, which is frankly what happened with Silksong. I did not expect to be writing this essay, but here we are.

What I’m working on:

Absolutely nothing. However, I just discovered I can put LATEX into these newsletters. I have no reason to do so, but I’m eternally tempted, so here’s a hydrogen 2p wavefunction: