Signifiers Pointing at Nothing - Trigun Stargaze

Hello hello! It has been a while (yes, Buttondown, I am aware, you need not remind me every time I open the dashboard that it has been nearly two months since I last sent an email). I’ve been rather busy with finishing a semester, finishing drafting my novel, and then slouching my way into the start of the next semester, as always seems to happen. I have, in fact, written scraps of a few other newsletters before finding myself deeply uninterested in the topic.

And then. Trigun Stargaze.

So, I’m taking an English course on adaptation theory, which means I’m just going to be even more obnoxious about, well, everything, than I already was. Also we just got our first assignment and I haven’t taken an English class in too many years so this is my attempt at getting back in that mindset. Also I’ve been watching Stargaze with my roommate and it’s. Uh. It’s bad. It’s bad in a number of ways I’m not going to get into, because I wanted to play with the idea of semiotics and the failure of Trigun Stargaze to effectively construct its own language.

Semiotics is “the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation”, in which symbols or signifiers take on meaning. Smoke is a signifier which unarbitrarily represents fire (in much the same way as how I quicken my pace when turning the corner onto my street and encountering a barrage of fire trucks), while “dog” as a word is an arbitrary representative of the concept of…well…dog. Rather hard to describe the semiotic system of language from within that language, but we make do.

Let us, as is always the case with these newsletters, talk about something completely different while I circle warily around my point. I recently read Annihilation for book club (which I had read before, when I was probably 14, which only furthers the running joke that I’ve actually read everything), and though I haven’t watched the movie in almost that long I have a fondness for Folding Idea’s video about decoding the metaphor [of Annihilation]1. My points about the movie will be largely taken from that video, while all analysis of the book is, unfortunately, my own.

In our first meeting (after reading the first two chapters), one of the other book club members lamented that she had seen a still from the end of the movie and so had been spoiled for the book, to which I snorted and promised her no, no, the book is entirely different. Nevertheless, I think that the film is a wonderful adaptation—what? Without fidelity to the source text? Unheard of for me to let such an affront slide.

Linda Hutcheon, whose work it seems much of my course centres around, abhors the presence of the fidelity argument in adaptation studies. The process of adaptation is the generation of a new work of art, not the mindless mechanical reproduction of a previous work, and insisting on fidelity between the works places too much emphasis on some ‘inherent artistic merit’ of the original work. She even refuses to use the term original work or even source work, seemingly preferring ‘adapted text’. Should adaptations then be judged purely on their own merits, without ever considering their relation to source work?

No, Hutcheon says, rather confusingly; the experience of the adaptation is based on the audience’s familiarity with the source text. Adaptations are then ‘palimpsestuous’ (god does my prof love that term), formed of half-glimpsed echoes of the source work, reimagined and digested by the adapter. Nevertheless, an adaptation must stand on its own merits, rather than relying on the artistic value of its source.

I personally subscribe to the simple question, stolen from the Terrible Book Club podcast: What was the author’s (adapter’s) goal, and do you think it was met?

One of the key symbols in Annihilation-the-book is the pool which sparks the interest of the then-child biologist, in which she watches an entire ecosystem evolve and change, undisturbed. This ties first into the ecological themes of Annihilation, but in many ways more importantly it acts as a signifier for isolation and, ultimately, loss. The biologist chooses again and again to reach for annihilation of self in these isolated places, impersonal one night stands on the edge of civilization, an expedition that would be “a death that would not mean being dead”. The loss of the pool is tied directly to the greater loss of her husband, described as “certain kinds of deaths that one should not be expected to relive…connections so deep that when they are broken you feel the snap of the link inside you”. Again and again, the abandoned pool, the distant tide pools, an empty lot, these places reflect the biologist and Area X itself, isolation which cannot save you from the connections which inevitably bring with them the grief of loss, which only changes its form, as you are changed by grief.

There are no tide pools in Annihilation-the-film. No abandoned swimming pools. No Ghost Bird. Instead, there is the ouroboros tattoo.

Film is an inherently visual medium; despite any dialogue, voice over, music or other linguistic tools, the strength of cinematic adaptations is in their use of imagery. Films are required to build a visual, cinematic language with which to communicate the ideas expressed in the source text. The effect of the tide pools as image in Annihilation-the-book is largely constructed due to the biologist’s narration, an effect which cannot be reproduced cinematically without losing the creative autonomy of film.

Where Hutcheon seems to imagine some agreed-upon language of cinema, meaning and metaphor prescribed and which any adaptor merely dips into to create meaning, film critic Jean Mitry presents a different argument: that an image becomes a sign, takes on meaning, by virtue of the symbolic value it acquires in association with other images (paraphrased). In other words, each piece of cinema must continually redefine its own language and the meaning of its symbols, and to do so it must acknowledge and control the associations created in the mind of the viewer.

Mitry presents this as though it were unique to the cinematic or photographic art form—language, after all, is prescribed. When I say ‘eternity’, you understand that word by its specific definition. However, when I say ‘eternity’ within the context of an analysis of Revolutionary Girl Utena, the symbol takes on a completely different meaning, despite being still a linguistic symbol, rather than a visual one. The definition of signs and symbols is not unique to pictorial forms, but rather to metaphorical constructions, which film just so happens to lend itself to. Words must be taken at face value on their own, but it is within the wider context of the text or work that they are able to be redefined. What does a tide pool mean, after all? Nothing. Everything. Context is the driving force behind the construction of meaning behind cinematic signifiers.

The ouroboros tattoo, first seen on one member of the expedition into Area X, slowly appears on the arms of other expedition members. It appears on the arm of a corpse, long dead, transformed by Area X. Did the man, now a bloom of incomprehensible fungus, have the tattoo before embarking on his own doomed expedition? Is the tattoo somehow a result of contact with the transformative properties of the isolated region?

It doesn’t matter.

“No matter what the diegetic answer may be, the symbol has taken on meaning through its association with each of these characters” (Dan Olson, 2019). The ouroboros tattoo becomes a symbol of the pieces of one another that we take into ourselves, of shared pain, and of our evolution and change through those we care for. Both Annihilation-the-film and Annihilation-the-book deal with the death of our individual selves and ask the question is it still worth it to make contact with one another, knowing that it may bring only greater pain, and both do so uniquely through their own language and signifying systems.

I wish this newsletter was just about Annihilation. If I had any self respect it would be. Alas, I promised myself a Stargaze bitchfest.

There is so much I could say about Trigun Stampede and its sequel Stargaze: messy characterizations, pacing, and a restructuring of events that I desperately want to give the benefit of the doubt (two 12 episode seasons vs Trimax’s 16 volumes, timing is tight) that nevertheless manages to diffuse much of the tension inherent to the narrative. Perhaps another time, for now, adaptation theory. Semiotics. Signifiers pointing at nothing.

I’ve been trying to put my finger on something that has been bothering me about the recent episodes of Trigun Stargaze, something I’ve landed on is what I’ve here described as ‘signifiers pointing at nothing’ which frankly belies a rather surface level understanding of the source material.

I’m going to focus in on two major symbols: Fifth Moon and Vash’s coat.

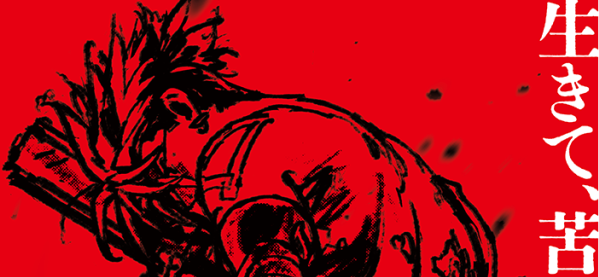

Fifth Moon is one of the most interesting repeated images in Trigun Maximum, if only for the fact that, much like Dan Olson’s description of Annihilation-the-film, it’s symbolically dense but frankly rather blunt. Actually, I suppose that much of Trigun could be accurately summarized similarly. At the end of the original run of the manga, before the shift to a new magazine and the Trigun Maximum tagline, the true, devastating power of Vash’s inhumanity (which had, until this point, been merely suggested by the non-existence of the town that used to be Julai) is revealed. He is transformed, his power taken against his will, and it is only through his own control that the power is redirected to score a crater into the moon above them. A few chapters later, Vash—having tried, and failed to escape from his past—is once again faced by the physical manifestation of his powers, his inhumanity, and loss of control. In the very way the panel is drawn, Fifth Moon beginning to eclipse Vash’s face, the stark shadows rendering Vash nearly monstrous coupled with the fear on his face, the symbol is made clear.

This is not subtle in its meaning—again, blunt, wearing its themes on its sleeves, but nevertheless dense. What’s important here is that Fifth Moon has become a symbol, it has become a signifier of the horror inherent in Vash’s very nature, in standing before something so much larger and more powerful than you could ever be. It is also, then, Vash’s guilt. Trigun Maximum has defined its own language, which allows further moments such as this:

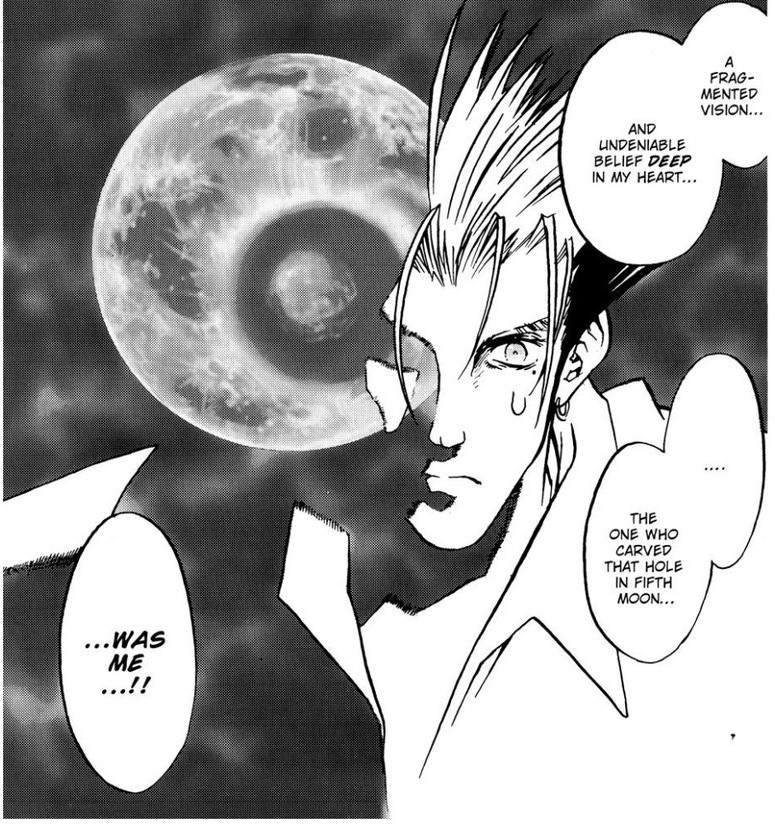

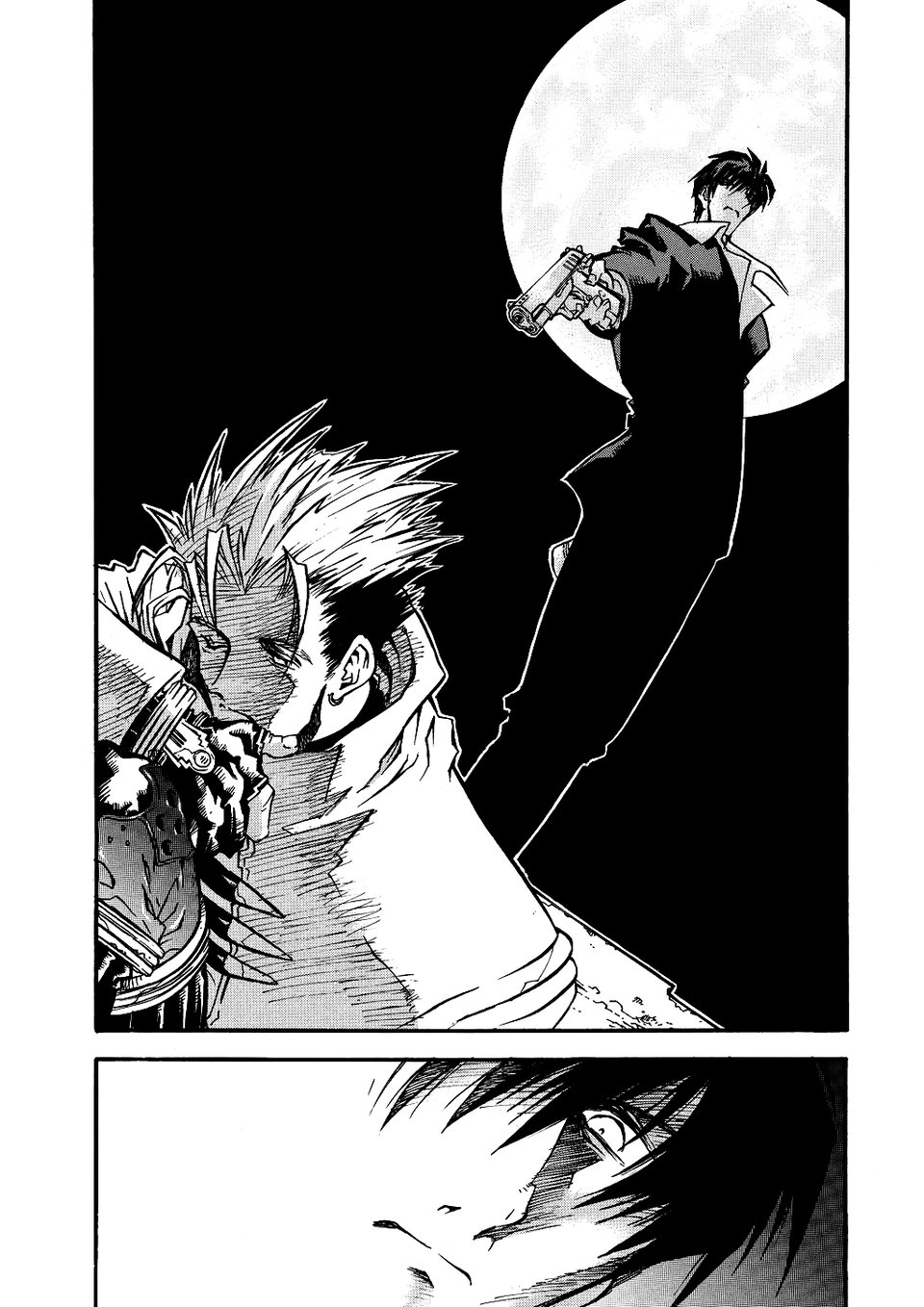

Wolfwood doesn’t have to say anything; we understand, we see Vash, smiling, backlit by the terrifying truth of his existence. The simple inclusion of Fifth Moon with its gaping hole communicates more to the audience than any line of dialogue could. We understand why he feels that this may be the only options, just as we know that Vash would accept his judgment. He, after all, saw the moon too. Such is the power of the symbols defined by a work. What does the moon mean usually? Love? Longing?

Abject terror. The destruction of your world and your personhood.

The very first episode of the new season of Trigun, Trigun Stargaze, opens with a shot of Fifth Moon, crater scored into its surface, debris encircling it…and then it cuts to Legato destroying a town and stealing a plant.

What, then, was the purpose of that first shot, the opening shot? To remind us briefly of what happened at the end of the last season, for one thing, which I will not begrudge it. Perhaps, generously, to tie the destruction of Fifth Moon to the destruction of the town, though here already the imagery and symbolism becomes somewhat messy. This, then, is a signifier pointing at nothing except the previous media as a way of making the audience go ‘oh! oh! I remember that!’. We’re only three episodes into the season, and I hope that the creators of the show put in just that modicum of effort to cement Fifth Moon as an actual meaningful symbol within the work—or, even, create an entirely new symbol, one which functions better in the medium they are working within. That is, after all, the power of adaptations: to take full advantage of their art form.

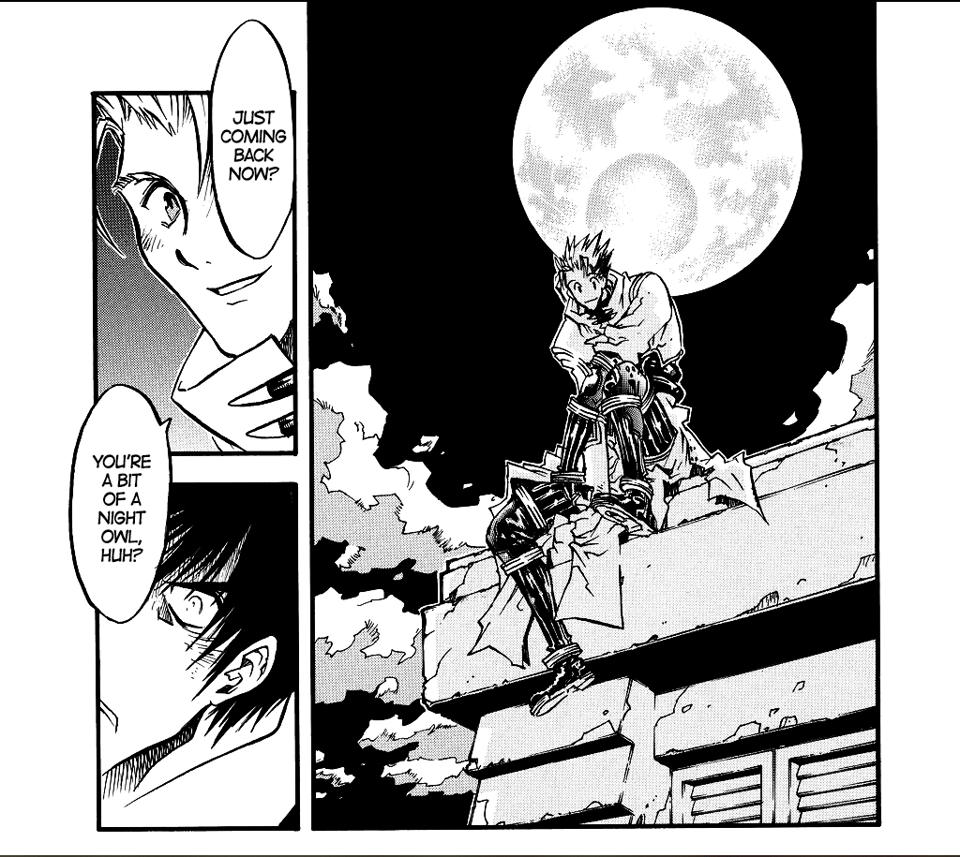

Next, Vash’s coat: this one is somewhat harder to pin down, not due to lack of meaning, but because it takes on a number of meanings throughout the manga. Vash the Stampede is in many ways defined by his red coat, his blond hair. In fact, we see many times the various thugs across Gunsmoke who fashion themselves after The Humanoid Typhoon, wearing long red coats to take advantage of the fear that comes along with the image. Vash as The Humanoid Typhoon becomes a symbol in and of itself to the planet at large, and so that is the first layer of the meaning signified by the coat: the person who destroyed Julai, someone to be feared.

Beneath that, though, are Vash’s own reasons for wearing the coat. Near the end of the first season of Trigun Stampede, while Knives manipulates Vash’s memory, red flowers are seen again and again. We see later how they are associated with Rem; she shows the young twins a geranium, and when Vash asks if they can eat the flowers the scene devolves into brotherly ribbing and a lecture from Rem reminding the boys not to use their powers in front of humans. The red flowers are then clearly associated to Vash’s memories of Rem, and likely to his grief and guilt over being unable to save her. This is, in fact, an effective use of a signifier, which would be more effective if the imagery of the red flowers appeared in more than a few scenes which are explicit call-backs to the ‘98 anime.

In the manga, however, the scene goes somewhat differently, specifically due to the context in which it is shown. That being that, Vash, having accepted that he will never be able to lead a normal life, once again takes up the mantle of Vash the Stampede, choosing to once again wear his familiar coat.

Vash is recognized as the character that has been created in the minds of the people of the planet in the moment that he dons the coat, and he uses that to his advantage to diffuse the situation at hand (which is ultimately unimportant). However, the scene near the beginning of the chapter, later adapted into Stampede, provides another layer of meaning, implicitly tied to the idea of the coat by its placement within the text:

Not only is the coat a signifier of the persona Vash has created, it also signifies his determination: to stick by his values, to stay alive, to remember his greatest failings. So long as he is alive, so long as he is Vash the Stampede, he is forced to carry the weight of his past, even as he hides it from the world beneath the cover of the coat itself. There is a reason that scenes in which Vash is seen bare are so impactful; without the coat he is vulnerable, he is without the safety of facade. Why does Vash wear a red coat? As a reminder, as a persona, as protection.

Why, in Trigun Stampede does Vash wear a red coat? Well, because it is with that coat that he is recognizably Vash. Yes, he tells the audience that he likes red because it reminds him of Rem, but within the cinematic, visual language of the show, Vash wears a red coat because he is Vash the stampede. I know what it signifies; you know, now, if you didn’t before, but that sign is not textual. The signifier is there but what is signified is lacking due to adaptational decisions, and it is not replaced by any other interpretation, image, or theme. An adaptation must stand on its own, merely supplemented by knowledge of the source text. It cannot be reliant on knowledge of the source text for its semiotic system to function.

Anyway. Anyway.

What I’m reading right now:

I’ve been sent an e-arc of The Universe Box, by Michael Swanwick, though I have to admit I got distracted by finishing Annihilation and then tearing through Authority.

An album to listen to:

Death in the Business of Whaling by Searows just came out and I am utterly obsessed. I saw him in concert a few years ago, and i intend to do so again this summer.