Read Weird! - The Last Days of New Paris

Yeah so, gonna be honest, fighting Nazis in Paris with the power of ::checks notes:: the physical manifestations of Surrealist art after the failed student of Aleister Crowley gets his hell box stolen by a common crook wasn’t on my book bingo for this year.

This is a weird one! Of course this is a weird one. What else could it be, truly, when I’m reaching out to you, beseeching you: read widely. Read well. Read weird. God, please read weird.

This is going to be one of those newsletters where I remind you that I am not an historian, a political scientist, philosopher or any of the dozens of other professions which would be more qualified for this type of essay. I am a scientist. I collate data, I pull at threads, I say things I don’t understand and pretend I actually worked through that proof rather than just copying it off Stack Exchange. Tell me I have my artistic movements mixed up, I’ve asked you every week, and by god, what I’m asking you to do is take what I say and run with it. Read weird books and surrealist manifestos from the 1920s.

I’ve been thinking again about that study I mentioned 1, in which English students truly could not understand the things they were reading, though this has largely manifested as me actively forcing myself to look up words I don’t know. It’s rare that a book I pick up (especially during term time, when my energy for actually challenging books is rather low) is so rife with unfamiliar words, and The Last Days of New Paris by China Miéville certainly took the cake among those I’ve read this year (besides, perhaps, Saint Death’s Daughter, which delights in its bizarre and archaic language). Beyond introducing me properly to the Surrealist art movement (yes, I’ve seen Dali’s art, yes I’ve seen the not-a-pipe, etc, but all that work lacked context) (I really should start rationing my parentheticals), it forced me to consider the limit of my knowledge even of the English language. ‘Lugubrious2’ and ‘exigencies3’ are two words I remember particularly, which I stared at and said to myself ‘well. These both seem nearly familiar, and I could perhaps make a guess, but it would be a far sight better to just pull out the dictionary’. Broadening the horizons of your knowledge etc. I suppose this doesn’t directly relate to what I meant to be talking about, but I believe that we should interact with works which challenge us, whether that be thematically or, simply, with words such as Lugubrious. Wonderful mouth-feel that—nearly as good as oubliette.

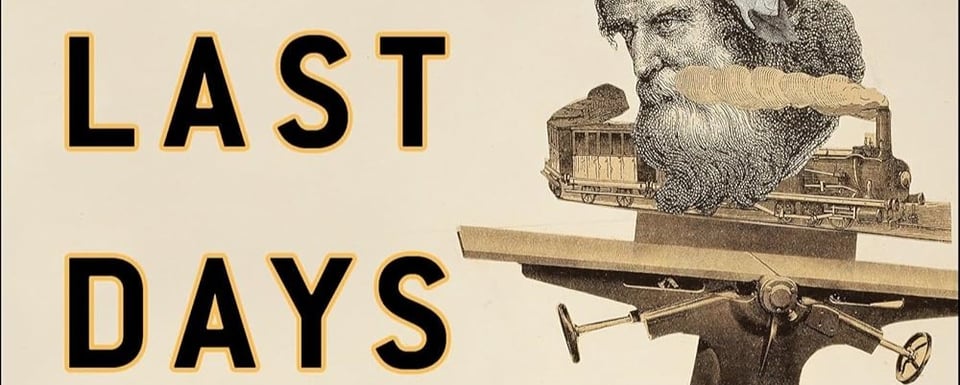

The Last Days of New Paris is, ostensibly, a novella about a young man in Paris in 1950 staging a losing battle against the Nazi forces still occupying the city. Of course, this is all taking place in a Paris where, nine years earlier, some great cataclysm caused the physical manifestation of all Surrealist art—of the dreams, nightmares, and hallucinations of an entire population—to walk the streets of the city, transforming the landscape around them. Exquisite corpses of bearded men breathing the steam of an old train twist the physical world to follow their own rules, pajamas grant the wearer superhuman abilities, and the very hordes of hell trample the remaining citizens at the bidding of the Nazis. However, because of course this is China Miéville, our expectations of the book-as-a-novella are subverted first by the suggestion by the text that this is merely a recounting of a true story told to the author himself, and then by the simple fact that this ‘novella’ is truly just a love letter to the Surrealist art movement, complete with a solid 20 pages of references to the various artists mentioned in the text at the end of the work.

I have two notes, here, asking me to talk about both Surrealism and The New Weird, and frankly I feel far more comfortable talking about current movements in speculative fiction than a wide-reaching artistic movements from the 20s and 30s4, but I suppose what I’m trying to point out is the places in which they intersect. Surrealism was a struggle against the rationalism dominating the west as technology, development, and global conflict dug their fingers ever further into the cultural landscape. Surrealism emerged from the Dada movement after the first world war5, and was inherently tied to what were, at the time as now, revolutionary politics. Entire schisms were formed among surrealist groups due to differing opinions on communist and anarchist ideals, and many surrealists were members of communist parties. Surrealism was the rejection of rational thought and instead encouraged the production of arts and writing which subverted expectations and presented the functioning of the unconscious mind over the conscious, rational mind.

In many ways, reading this novella made me sit up and point, both at Miéville and the New Weird literary movement of which he is a key figure. The New Weird is something of an offshoot of the slipstream genre, which I talked about somewhat in my musings on genre back towards the beginning of the summer, and which focuses on breaking the expectations of traditional speculative fiction. Much as slipstream is rather had to define, so too is The New Weird—how best to describe a literary movement in which each story completely tears itself free of rational logic, while still playing with the very genre conventions which it seeks to subvert? Miéville, VanderMeer, others I would hesitantly say edge into the movement though may not consider themselves a part of it, all create works of Surreal art all while laughing behind their hands and holding classic science fiction, fantasy, and horror behind their backs.

Is The New Weird still tied to politics in the way that Surrealism was? Harder perhaps to say; much as the internet has provided us with so many new ways to connect and interact with one another, political and artistic movements are so much more disperse than they were a century ago. No longer do small groups meet in coffee shops to discuss their ideals, these things instead are spread across forums, social media, and private messages. Revolution has never been so accessible and so disconnected. This kind of weird fiction, this surreal art, could never become the cultural norm—what is normal is no longer weird, and it is strangeness and unfamiliarity which frightens those in power, and those who expect the world to go on exactly as it has the day before, and the day before that. Insert that Vetinari quote which I now cannot for the life of me find.

In many ways my experiences with this book tie back to the very themes of the book itself: fascists cannot make great art. The Great Men6 in power at the top of everything cannot make great art. Those who represent the power structures of our world cannot write stories, cannot paint images, cannot create music which challenges those power structures, and it is in that challenging of power that true art is born. Art is a revolution against “the system” because we live in a society which does not value art unless it is in the incredibly limited form which can serve it. In 1937, the Nazis opened two art galleries: The Great German Art Exhibit, and concurrently the Degenerate Art Exhibit. The Great German Art Exhibit was meant to show the triumph of Nazi art, showing the power of the state and the rational, powerful Germans within it. It was about strength, power, and capitulation with its patrons. The Degenerate Art Exhibit was meant to be a direct mockery of the art housed within its walls—look, there across the street, to the great art of our glorious empire. See now the pathetic attempts of those ostracized by the state. See the bizarre art and the outpouring of the unconscious mind. Point and laugh.

600,000 people visited the Great German Art Exhibit.

The Degenerate Art Exhibit received over 2 million visitors.

This is a fact I think about regularly, and one of the things which has stuck with me. Why? Perhaps because the success—or, arguably, failure—of the perfectly prescribed Great German Art Exhibit is so wonderfully presented.

Can art be revolutionary? Can consuming art be revolutionary? I think those are both complex questions with complex answers, and I doubt I can get all my thoughts out in a single essay. I think the first thing to address is that the consumption of art in our current society is treated as just that: consumption. You can read a thousand antifascist books, watch documentaries about prison abolition, listen to Palestinian poetry, but in the end what have you done to directly affect any of the things you try to care about?

The first step to progress is understanding, is it not?

This disconnect between the creation of art and direct action is explored in the secondary narrative of The Last Days of New Paris, in which Jack Parsons looks on the Surrealists with derision as they sit in their grand and decaying villa, playing games while the Nazis creep ever closer. Their art seems frivolous, pointless—what changes are you actually making in the world, drawing your exquisite corpses? Of course, this critique is rather offset by the fact that we know that the art of the Surrealists is making a genuine difference, ten years later in the changed streets of Paris. Then of course I end up looping back to my original feeling: yes, the manifs are powerful, yes they’re tangible, and yet the citizens of Paris are still locked in a standstill against the Nazis. It is 1950. The war should have ended 5 years ago. Pull on your pajamas, take up your gun, choose each and every day to try to make a difference, driven by the art and words of your former comrades.

Perhaps a better phrase would be: I think that engaging with art can be revolutionary. When talking about dictatorships in my (shudder) high-school classes, we often discussed how much control the government truly had over the ‘hearts and minds’ of the populace as a measure of the actual power and control of the dictatorship, often accompanying a discussion on propaganda. Control the media, control the art produced, you control the ideas that are available to the general public. There is a reason that book bans and burnings are some of the first markers of a rising authoritarian state—if you don’t know that there is any other way to think, how can you think in any way other than the one those in power want you to. Perhaps art itself isn’t revolutionary, but the creation of art in spite of the world we live in can perhaps be. Just—as a first step. You can’t stop now. You can’t stop now.

What I’m reading right now:

I’m currently finishing up The Dispossessed for book club, which I have actually read before, but it was long enough ago that I was a rather different person and I don’t remember much. Being able to actually talk through the ideas and our reactions to them, rather than sitting on a literal island in a lake in the woods has been very interesting, and definitely influenced the tone of this newsletter somewhat. Also, I finished The Sapling Cage, which means I’m now 5/8 of the way through the Le Guin award nominees.

An album to listen to:

I usually try to find music that may, perhaps, be new to people, however it would feel wrong to not include In The Aeroplane Over The Sea, by Neutral Milk Hotel this week. How could I top strange and surreal songs about Anne Frank and the second world war? Anyway, it’s been one of my prime study albums recently.

What I’m working on:

Besides surviving the end of the semester? I made a bet with myself that I could get Stars Like Darting Fish to 50k words before the end of November (in something like memory of NaNoWriMo). This week, I’ve been trying to get through a series of scenes I’d left blank up until now, because they’d a bit different to the rest of the story. I hit my goal, for the record.

Carlson, S., Jayawardhana, A., & Miniel, D. (2024). They Don’t Read Very Well: A Study of the Reading Comprehension Skills of English Majors at Two Midwestern Universities. CEA Critic 86(1), 1-17. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/cea.2024.a922346. ↩

“Mournful, dismal, or gloomy, especially to an exaggerated or ludicrous degree.” ↩

“The state of being urgent; pressing need or demand; urgency: as, the exigency of the case or of business.” ↩

I told myself, ‘you can sit down and read André Breton’s surrealist manifesto. It would not do to speak on something you do not truly understand, save a quick google search’. Readers, I was not strong enough. I have, as always, band structures to calculate. ↩

Voorhies, James (October 2004). "Surrealism". Metropolitan Museum of Art. ↩

Carlyle, T. (1840). On Heroes, Hero-worship and the Heroic in History, although I’ll admit that I always think of Great Man Theory with Lynch. Can’t escape him. ↩