October 23, 1976: the Host is Steve Martin and the Musical Guest is Kinky Friedman

Here's some stuff that happened in the past

Steve Martin was made for Saturday Night Live because he was hip and popular and game for anything, but also because his persona as the ultimate show-business phony has so many commonalities with the personas of Albert Brooks and Andy Kaufman.

In his 1970s heyday, purposeful insincerity was Martin's trademark. Everything was a put-on, a goof, a lark, a gag. Martin protected his fragile artistic soul by harnessing the incredible power of irony.

In his stand-up act, Martin was phony. He was narcissistic. He was playful to the point of being borderline Dadaist. But where Brooks and Kaufman were cult acts beloved primarily by fellow comedians and post-modernists, Steve Martin exploded into the mainstream like few stand-up comedians before or since.

Martin wasn't just an unusually popular comedian; he was a pop culture phenomenon. Martin is a smart man who made stupidity a key component of his brand.

For someone who was perhaps the biggest comedian in the world at one point, Martin had an impressively strange act, but he pulled it off because he had bullet-proof confidence and because his act worked on multiple levels.

For the smart set/brainy crowd, the genius of Martin's act was that it made people question the very essence of comedy and explore what makes them laugh and why.

There are ironic air quotes around everything that Martin does during his first trip to Saturday Night Live, but they're not visible to the mouth breathers, ignoramuses, and future Trump voters of the world.

To the mouth breathers, ignoramuses, and future Trump voters of the world, a man with a fake arrow through his head is just plain funny.

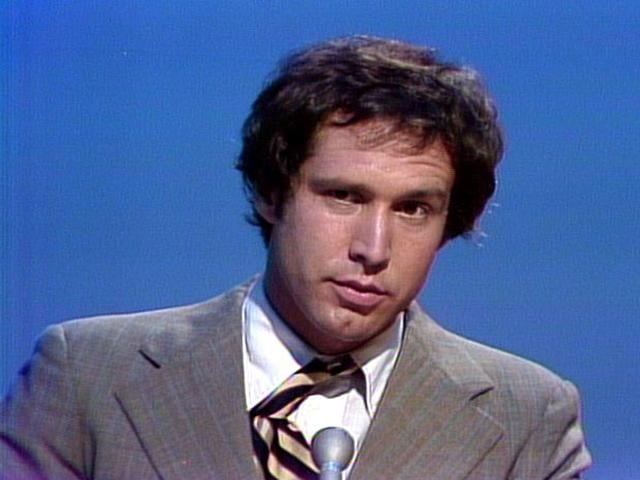

Martin swaggers onstage for his opening monologue like he owns the place, like it's his new home and not just a place he would sometimes visit. He would not be wrong. Steve Martin got more out of Saturday Night Live than anyone who was never a cast member, producer, or writer.

Martin and Saturday Night Live enjoyed a symbiotic relationship. Appearing regularly as perhaps the most loved host in the show's history made an already incredibly popular performer even bigger and even more ubiquitous.

Saturday Night Live, in turn, benefited tremendously from its close relationship with one of the most popular living Americans of the mid-1970s.

So, I was a little surprised by how relatively underwhelming Martin's first episode is. Musical guest Kinky Friedman only sings one song, a heartbreaking acoustic number about growing old.

In the first season, it was not unusual for the show to have two musical guests who performed two songs apiece. That helped writers because they could write fewer and shorter sketches because musical guests and wildcards like Andy Kaufman took up so much time.

That helps explain why some of the evening sketches drag on interminably. The most egregious offender is a Beatnik sketch that seems to last roughly half of the show's 90 minutes.

The entire cast gets a turn at playing cartoonish anti-authoritarian hepcats rebelling against a grey world full of squares, propriety, and conformity. If any juice or life was left in the subject of beatniks, this sketch sure did not find it.

You can feel the show becoming more commercial and predictable in this episode. The show had done television parodies before, most notably in the legendary sketch about the cancellation of Star Trek, but they were not yet a fixture.

This episode has multiple television parodies. In a parody of the famous "Chuckles Bites the Dust" episode of Mary Tyler Moore Show, Steve Martin's smarmy Ted Baxter accidentally kills Mary, to the mortification, if not surprise, of his coworkers.

The sketch aspires to the cheap buzz of recognition in lieu of having anything to say about the episode specifically and the show in general. The sketch drags on and on in the way, sub-par sketches inevitably would in the years and decades ahead, serving as silent but persistent reminders of just how hard it is to fill 90 minutes of live television with quality every week.

The other television sketch imagines what Jeopardy would look like in 1999, seemingly re-using the Star Trek uniforms from an earlier sketch. It's a sketch most notable for the meta-dig it takes at its much-hated star in the form of the answer, "Comedian whose career fizzled after leaving 'NBC's Saturday Night.'"

The answer is, of course, Chevy Chase, but the joke is notable primarily for its sour bitterness. It's also worth noting that in 1999, Jeopardy would still be on the air, as would Saturday Night Live, and one of the show's most popular recurring sketches would be Celebrity Jeopardy.

In 1999, Jeopardy would be a priceless showcase for two of its future stars, Norm MacDonald and Will Ferrell.

The sketches that score tend to be on the bizarre side, like a wonderfully kooky bit with Steve Martin as the author of a book about athletes and sex and how, true to superstition, any athlete who has sex before a match will be terrible while athletes who refrain from sex will be extra potent.

It's as silly as a bit about a "digital watchdog" that's a dog with a clock attached to it.

Martin made a striking impression in his first time as host despite sometimes sub-par material, but the best was yet to come.

Grade: B-

Best Sketch: Looks at Books

Worst Sketch: Plato's Cave

You just read issue #38 of Every Episode Ever. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

-

It funny how SNL and Muppets were so incompatible, and yet Steve Martin was ideal host for both shows.

Add a comment: