It's March 19th, 1977, the Host is Broderick Crawford and the Musical Guests are Levon Helm, The Meters and Dr. John

Here's some stuff that happened in the past

I wrote a blog post not too long ago on the problematic nature of Bill Murray’s persona and his image as not just an unusually talented and beloved actor but also a modern-day folk hero with much to teach us about living life to the fullest.

This veneration of Murray and his unwillingness to follow the rules or respect boundaries, particularly those of his female costars, has troubling ramifications that speak to the dark side of hero worship in general and hero worship of the Caddyshack star in particular.

Dudes don’t just love Bill Murray; they worship him. He’s a God. He can do wrong, including all of the things he does that are objectively wrong.

So it is strange to think that there was once a time when the future comic icon went on television to address the live and home audience of Saturday Night Live to half-jokingly, half-earnestly ask them to like him.

Yet that’s just what happened on an episode early in Murray’s time on Saturday Night Live as the first Not Ready For Prime Time Player who had not been with the show since its debut.

A seated Murray seems nervous for a very good reason. By asking for the public’s approval, laughter, and cards of support, the funnyman was making himself vulnerable in a manner that must have been terrifying to someone whose language was that of sarcasm, irony, jokes, and smartassery.

Lorne Michaels thought that Murray had gotten off to a less-than-roaring start on the show that did not reflect his true talent or what he was capable of. Murray consequently only seems to be partially joking when he says that his buddies all tell him that he’s hilarious in real life but not funny on Saturday Night Live, a comedy show, and ask about the disconnect.

Murray anxiously concedes that he just doesn’t think he’s making it on the show, but with the audience’s help, that can change. Murray implores the audience to be on his side, to root for him, and to be emotionally invested in his success on the show and outside of it.

It’s an early indication of the importance that personality has always played on the show and how what we see onscreen serves as a funhouse mirror of the behind-the-scenes shenanigans.

I actually think that there is a great hour long drama to be made about a Saturday Night Live-like show, but only if it really highlighted the importance of satire and its ability to hold the powerful accountable through laughter.

Murray talks about being one of nine children, the eldest of whom, Brian Doyle-Murray, would soon become a Saturday Night Live writer and sometimes performer, and how his father died when he was seventeen.

There’s an unmistakably melancholy and bittersweet quality to the whole affair. It’s designed to humanize Murray, to let us see him as a human being with an Irish sadness deep within his soul. On that level, it succeeds. It’s not supposed to be laugh-out-loud funny but rather endearing and revealing of the new guy’s character.

It’s hard not to watch it through the prism of historical irony, particularly considering that on Saturday, I saw a new blockbuster whose big hook, commercially, is that Bill Murray answers the feverish prayers of countless sad fanboys by slapping on the old uniform for the kind of glorified cameo that gives lazily going through the motions exclusively for the cash a bad name.

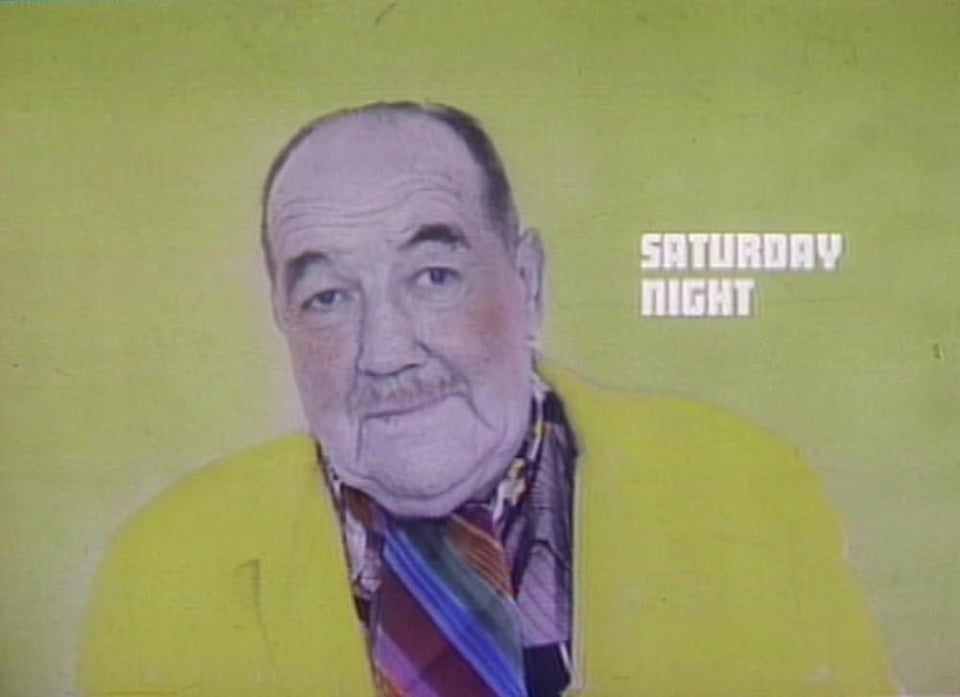

Beyond Murray’s oddly poignant, affecting Jeb Bush “Please clap” monologue, the sixteenth episode of the second season is notable primarily for the advanced age of its host.

Broderick Crawford was in his mid-60s when he stopped by 30 Rock to mix it up with the Not Ready for Prime Time Players, but he seems much older. This is largely due to the sedentary nature of his performance. He performs a monologue that consists largely of an Abe Simpson-style rambling anecdote in the same comfortable chair that he introduces musical acts Levon Helm, the Meters and Dr. John.

There’s a Highway Patrol sketch that Crawford is seated for. He also plays a sleeping J. Edgar Hoover being awoken by Dan Aykroyd’s Tricky Dick. The show’s strategy with Crawford was to not make him stand up or appear in too many sketches playing characters different from the ones he’s known for.

The episode begins with yet another girl group song, a Howard Shore specialty, this time with Gilda Radner singing about her love of saccharine and how she just can’t believe it does all the terrible things people say it does.

It’s similarly hard to watch the many songs, sketches, and monologues that Gilda Radner does about her complicated and painful relationship with food without thinking about the actress’ real-life eating disorders.

Everything became fodder for comedy on the show, particularly the cast’s vices.

Radner resurrects Baba Wawa for a spectacularly silly sketch in which she interviews Godzilla, who John Belushi plays as a typical show-business phony excited to work his way up the show business ladder.

She has another standout sketch in which she plays Lucy Ricardo dealing with a rascally conveyor belt. Only instead of pies or gadgets, nuclear warheads come roaring onto the conveyor belt faster than her overworked two arms and hands can handle.

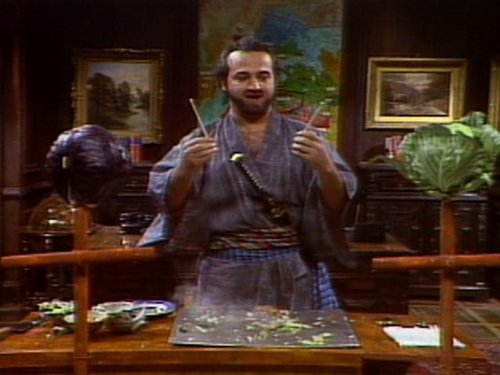

Belushi donned his Samurai garb for a sketch in which he played an assassin who went undercover as a chef at Benihana. The Samurai sketches were vehicles for the purest physical comedy this side of The Party.

Like The Party, the central funnyman is a white man playing an Asian. Sellers’ casting was controversial even then, but I don’t seem to recall any kind of uproar about Belushi playing a Japanese Samurai, in part because it’s such a goofy, affectionate performance and because there’s no make-up involved.

Samurai sketches with make-up prominently involved would automatically become very sketchy. This sketch is a standout because food is inherently amusing, and it’s funny to see him prepare dinner with the same flair he otherwise devotes to martial arts and a wide range of different jobs in any number of professions.

For better or worse, people didn’t seem to think too much about cultural appropriation back then. Besides, the upside to having white people play different ethnicities and even races is that you don’t have to cast people of color for those roles so the cast can remain blindingly white.

I doubt that Crawford picked up on the weird, drug and competition-fueled dynamics at 30 Rock. That’s probably for the best. He wasn’t asked to do much as host and acquitted himself just fine for an episode with one unforgettable plea for love and acceptance from someone who would go on to become one of the most beloved American entertainers of all time and some solid laughs and tunes.

You just read issue #53 of Every Episode Ever. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: