On staged stillness, and the shade of a giant foot

About dancing, documentaries, marble limbs, and the almost-invisible gestures hiding inside stillness.

Hoi!

For the last ten years, I’ve spent my Monday evenings dancing. While I first pushed myself into a dancing routine to escape the realm of words, my writing brain has always been drawn to the moments when we don’t move: the anticipation on the floor before the music starts, the subtle freeze that prepares the body for a spin, that fraction of a second a foot seems to hang still in mid-air.

The tension between movement and stillness is something I keep returning to in my writing. Not always successfully, I must admit. As Martha Graham said, the body says what words cannot. I’ve learnt the hard way that she’s probably right.

But every now and then, I come across a work of art—a film, a sculpture, a piece of clay taking shape—that captures something a body does in passing, holding it still long enough for us to really see it.

So here I am, at it again. Hoping I can use words to speak about bodies held still in time. No easy pudding, but I’ve decided that this newsletter must also be the place for the ones that haven’t quite risen yet.

From my desk

Words that found their way onto the page.

I went to see Below the Clouds at IDFA, a film on Naples by the Italian director Gianfranco Rosi. As a closeted volcano lover, I was looking forward to seeing the iconic cone of Vesuvius among the clouds. Instead, the camera took us into museum basements, where the flashlights of conservators bring Roman statues into view; into secret tunnels, where firemen follow the trail of invisible tomb raiders; into the belly of a ship, where Syrian refugees build volcanoes of Ukrainian grain.

The film constantly hovers between what is lost and what is captured. As archaeologists and conservators swipe dust from the eyes of ancient inhabitants—bodies fixed in stone and lava—its current dwellers call the fire department to ask about potential eruptions that might bury them. The then-ness rubs against the nowness. Traces of an age-old eruption meet those of an imminent one. Memories of a Southern war blend with those of a Northern one. The past keeps its habits, this film seems to tell us, and yet nothing stays the same.

“Everything is moving,” one of the conservators says while standing among giant marble heads, limbs, and other body parts. Even these displaced statues—hard, cold, lifeless—move. They have been her friends for thirty years. Their subtle motions through time move her, and through Rosi’s gaze, they move me.

But maybe I’m easily moved.

My friend, whom I saw the film with, mentioned afterwards that some of the shots felt too indulgent for her taste. I had to admit that I couldn’t get enough of the dramatic shadows on the smooth nudes, the almost-sculpted observations of the conservators, the staged choreography of the boat workers. I loved the artificiality of it all—the way Rosi’s exacting gaze drags certain things into view while letting others fall back into the dark.

Even after years of watching films critically, it remains easy for me to forget that the world a camera opens is different from the one the naked eye can see. Below the Clouds is a tightly woven tapestry of fragments, a vision of Naples the way Rosi wants us to see it. It might have nothing to do with the truth, but it does show what attention alone can construct—and conserve. With his camera, he breathes life into that which seems to stand still and brings to stillness what is constantly moving.

Of course, this is a truism not unique to Rosi’s films. On the train back home, I was reminded of an essay I once wrote (in Dutch!) about Eadweard Muybridge, a pioneer of what we now call motion studies. He created sequences of frozen images to study moving bodies. His stills revealed motions the naked eye had always missed, but they also show the human body held in scripted shapes, trapped in contexts that were anything but natural. I discovered a strange truth in those images: sometimes we need staged stillness to understand what’s moving, and vice versa.

I still hope writing can do the same, but more on that later.

From other desks

Words that reached me from other rooms.

In 2017, I graduated with a thesis on the animated GIF. One of the chapters was fully dedicated to gestures, a subject that lingers on in my tabs. Here’s an overview of things that came to mind while writing the first part of this newsletter:

I’ll open this block of hyperlinks with “I thought, as I wiped my eyes / Penelope did this too”, the opening lines of An Ancient Gesture (1954) by Edna St. Vincent Millay, on how our movements might be both authentic and antique. I found this poem through a book I’m reading called Homer and the Poetics of Gesture by Alex Purves. Niche, perhaps, but worth mentioning. She considers gestures as a process of articulation of joints and limbs just as an epic verse does through verse and meter. I also reread The Last of the Valerii (1874), a short story by Henry James, about a newlywed couple who live in an Italian villa, and decide to dig up the yard in search of ancient gods. As we learn from films like La Chimera, it’s usually better to leave them to rest.

Instead, one might search for sculptures that are not yet buried. A few weeks ago, I went to see the Mark Manders show Mindstudy at museum Voorlinden, which was filled to the brim with bodies frozen in time. Afterwards, I read Why Do We Have Time to Think About Our Bodies? (2004), in which Manders writes about the popular notion that each moment forms its own universe. He finds this notion absurd. “Just put a scratch on an LP and you will know for sure that something has changed in the world.” He believes in time as a line, not a cloud, and I tend to agree with him.

Through this exhibition, I also discovered a creature with a bodily posture I love, the Skiapode. “They are commonly described or depicted as figures with a single obnoxious large foot, who are in the habit, as Pliny the Elder remarks, "of lying on their backs, during the time of extreme heat, and who protect themselves from the sun by the shade of their feet". I hope you’ll enjoy them as much as I do.

And to end this block of text with a non-wordy treat (and celebrate the birthday of my dear friend Ilse!): 78 Tours (1985), by the Swiss animator Georges Schwizgebel. Movement pur sang.

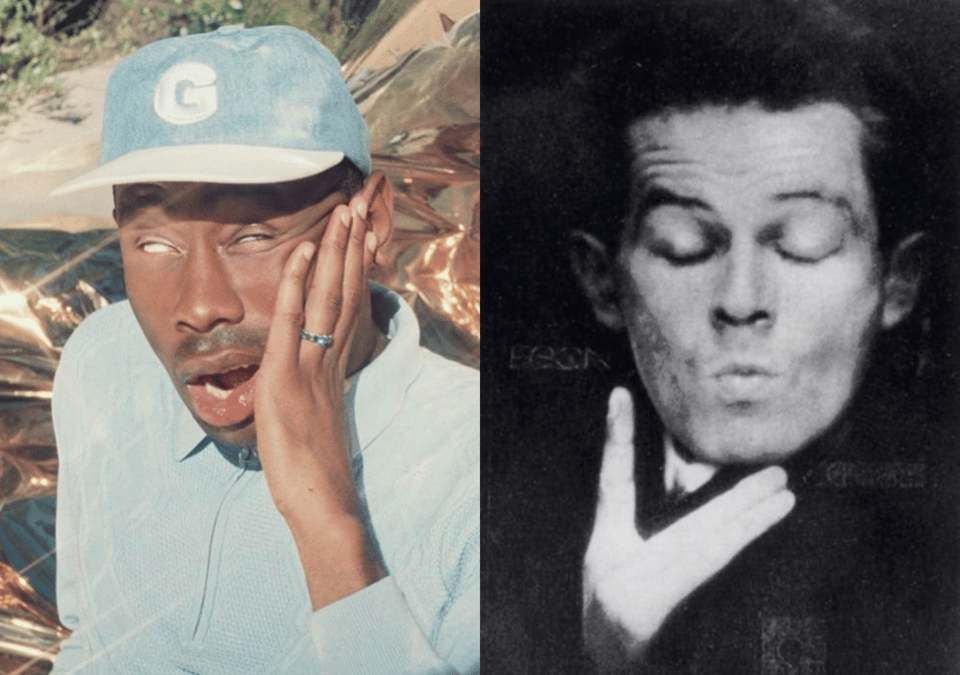

Diptych

Two images that found each other across my desktop.

I name this: “I thought, as I closed my eyes / Egon did this too”

Thank you for reading! It has been a long one, will make it shorter next time around, I promise.

May you enjoy some pudding.

Groetjes,

Iris

Add a comment: