In which going home again is like finally watching a jaguar eat a capybara in an animal documentary

look, some of us had weird hobbies BEFORE the pandemic

In the spring of 2016, some capybaras escaped from the High Park Zoo in Toronto. After a month of half the country breathlessly waiting for news of them, it was announced that they had been safely caught and returned to the zoo. You will never convince me that they were the original capybaras, though. I think they were replacements, because we, as human beings, are ill-equipped to handle the death of cute things, and capybaras are, usually, pretty darn cute. (Sidebar: this is actual plot of Penguins of Madagascar, which, as an avid animal doc watcher, I find endlessly hilarious.)

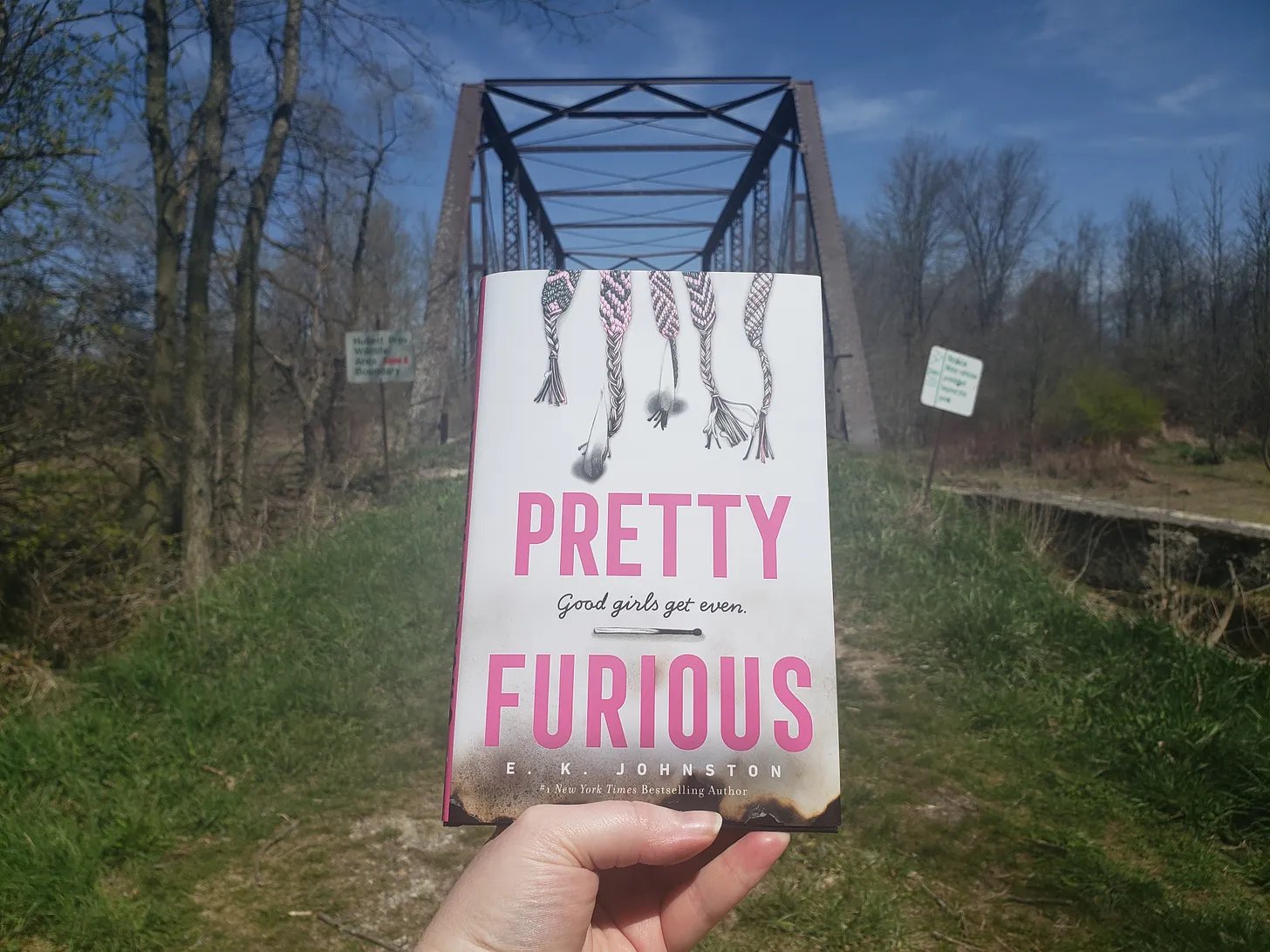

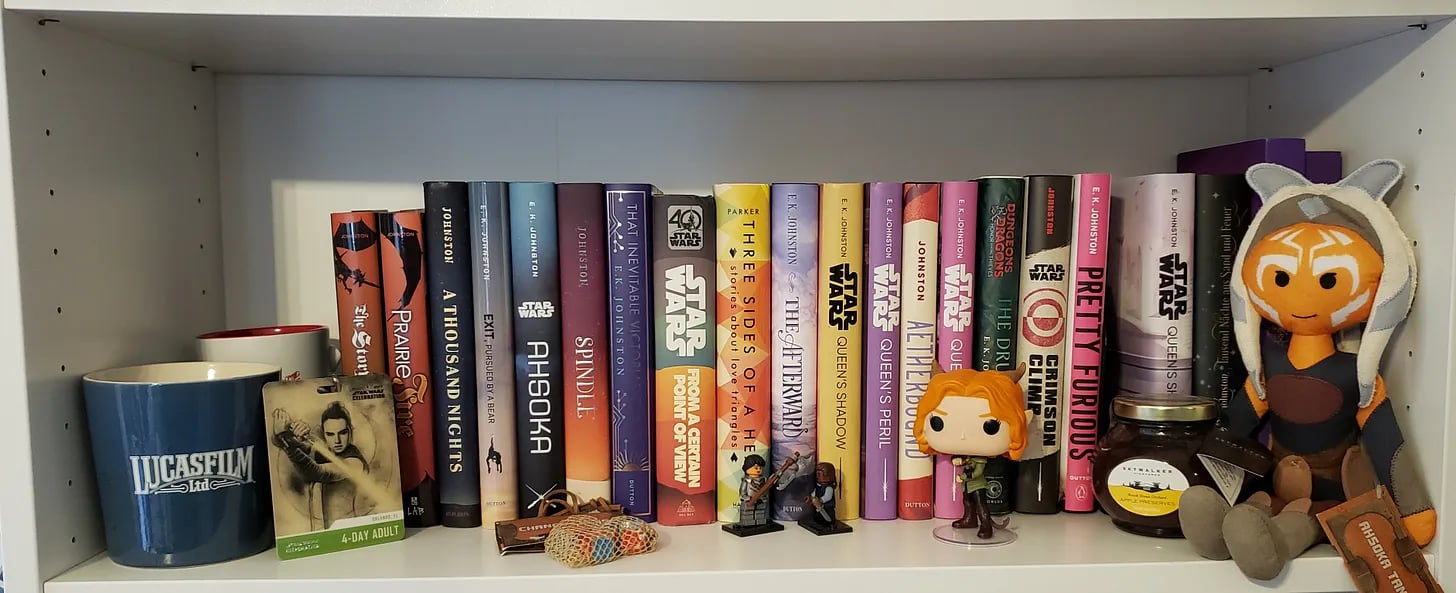

Anyway. I never imagined I’d be the sort of writer who set books in my hometown. This is for two reason: first, I never really imagined being a writer, and second, once I realized that I was, I assumed I’d write fantasy. Obviously this fell apart immediately, because The Story of Owen very much takes place in my specific Seaforth/Clinton mash-up, and then I did the same with Prairie Fire, Exit Pursued By A Bear, Fanny in That Inevitable Victorian Thing, and, of course, with Pretty Furious. When my friend Colleen was reading Ahsoka, she emailed me and said “I’m just getting into it, but your small town is definitely showing”. Apparently it’s my thing.

I forget how many times I’ve seen it, because when I am in a depression spiral I rewatch animal documentaries on loop, but I am reasonably sure that in at least 3 of them, we watch a jaguar try and fail to eat a capybara. David Attenborough tells us about how hungry the jaguar is and how it needs a successful hunt soon, because the timeline is getting critical. We watch it stalk the capybara on the riverbank, and then we watch the capybara escape into the water. Ultimately, we watch the jaguar hunt and eat a cayman, after some thrilling narration about two predators putting it all on the line. For some reason, it always strikes me as extremely bizarre. Plot armour is one thing, but who are these capybara paying off?

When you go back to your town, everything is smaller. The buildings aren’t exactly as you remember them and the shops have changed. The people are either new and unrecognized, or the same, and smaller because they haven’t changed in the same ways you have. And the teenagers, the ones who were children when you left, haunt all the mostly-familiar places in different ways. They have new jokes, new problems, new goals. It can be a little off-putting. And they don’t really care. They are in charge of the story now and , as much as that terrifies the adults, they are going to shape the narrative in the way that makes the most sense for them.

We don’t generally think about narrative structure when we think about documentaries, because they’re about real stuff, and we’re taught that facts and stories are mutually exclusive. It’s a lie, of course. Everything has a narrative structure, even the literal news, and everything is biased whether it wants to admit it or not. Animal documentaries make you care about a baby elephant and then watch as it wanders off alone into the desert. Then they make you care about a lioness so you won’t feel bad when it eats a different baby elephant. Constructing a narrative is how we get people to pick sides. Some people are team prey, and like it when the animal gets away. I’m team predator, and get extremely anxious if the hunt is unsuccessful. If you think I’m in any way exaggerating, go and watch this clip from Green Planet about a waterlily (also if you’re reading this as an email, the video might just be down at the bottom).

Small towns are changing. There was always a drug problem, but now there’s human trafficking, too. The people who move in are first or second generation Canadian, but they aren’t Dutch anymore. It still takes two hours to get to the airport, but somehow, it seems so much closer, so much easier to go out and look around. Your parents have bought a house that doesn’t have a bedroom for you in it. Some cling to “the good old days” without fully realizing what they’re asking kids, mostly girls, to give up. It’s taking time, but the narrative is shifting. As a YA writer who lives in a small town, I vacillate between wild hope and absolute exhaustion. And I don’t have to do math at 9am anymore. There are new heroes. And the old heroes don’t necessarily stay that way.

There’s usually a new documentary on Netflix around Earth Day. They’ve started to bring in new narrators, mostly because David Attenborough is back to working pretty exclusively with the BBC, and Netflix doesn’t broadcast those ones. I don’t love it, obviously, but I watch them because they’re good for cross stitching and occasionally I learn something new. This year’s offering was narrated by Cate Blanchett, and it was…fine, I guess, though the animals were a bit anthropomorphized for my taste and there wasn’t as much science as I prefer. Still, at one point we ended up in South America and she was talking about re-wilding to help nature recover. In Argentina, they ran into a problem they hadn’t predicted, because there was an explosion in the capybara population, and now the capybaras eat too much of the grass for the wilderness to re-establish itself. I sat up on the couch, staring at the TV in near disbelief: They were giving the capybara a villain storyline. You’re allowed to kill the villain.

I meet enough kids that I don’t worry about the future. Well, I don’t worry about them. I worry about what we’re doing and what we’ll leave behind, and I worry about the trauma we’re inflicting on people who are just trying to finish high school while the world is on fire all around them, but I don’t worry about the kids. They care, and they want to do better, and they’re angry, and hopefully that will hold on long enough for them to make it into positions of power. We shouldn’t make them save the world, but if we’re smart, we’ll pay attention when they try to do it. They know who the bad guys are, and we might not like it, but they’re going to fight in their own way.

The health of any ecosystem is measured by the strength of its predators. Reefs are at their best with a healthy shark population. Deer need wolves or they overrun the limits of what the local flora can support. We need otters to eat sea urchins to maintain kelp beds in the Pacific. But predators are usually the first targets when humans get involved. We villainize them, make them the competition, and that makes it easier for us to get rid of them. At a certain point in any re-wilding effort, they must be re-introduced. In Argentina, it began with a jaguar and her twins, the first wild jaguars in that area since the 1950s. And the whole plan depended on her ability to learn to hunt capybara. And she did. Right on screen. I never thought I would see it, and yet there it was: a successful capybara hunt.

The narrative is changing. We understand more, now, about how the world works and how we work inside it. The capybara have cut down all the grass and exposed the flaws in the system. We’re at a tipping point. We have all of the paths laid down before us. Most of the good ones will be hard.

But the jaguars are ready, and they are pretty furious.

Pretty Furious is now available for purchase at any bookstore in North America, and available to order at any library. There are also ebook and audiobook options, and you can get those at the library too! If you like it, please leave a review on a site like Amazon or Goodreads. If you don’t, well, maybe just never tell me you read it in the first place. :)

You can check out the rest of my books on my website, where I also have information about my editorial business and other contact info.

If you get this as an email and hit reply, I do get your message, but it’s a challenge for me to respond. If you comment on the actual site, it’s much easier to interact.

Due to politics and outright lies, UNRWA, the organization that helps Palestinians, particularly those in Gaza, is in desperate need of aid. You can donate once or set up a monthly donation plan here.