Happy Batman Day! A lost, appropriate piece.

Kept intending for years that one Batman Day I’d run an old article of mine from my freelance period that for various reasons never saw the light of day at the time. Today I finally remembered. Enjoy!

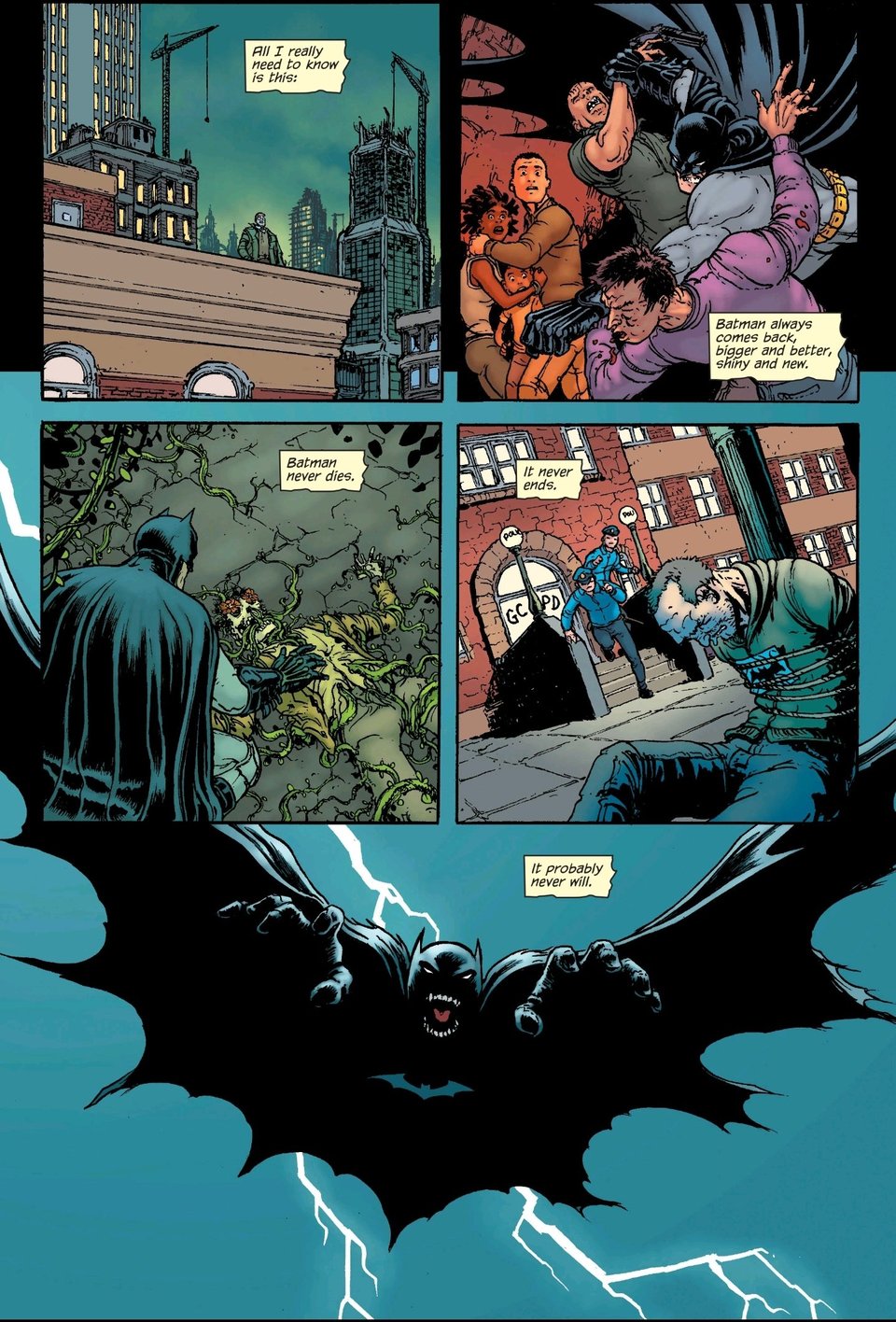

Tomorrow Belongs To The Batman: On a single page of Batman #700

Time and the Batman: Underrated as anniversary issues go! It’s somewhat understandable, the three eras/three stories that are really one/three artists gimmick is undermined by Quitely only doing half of his section and the remainder being picked up by Scott Kolins, and the traditional backup features were negligible here. But it was a big standalone Batman adventure at the height of Morrison’s popularity working on the character, the one time we got to see Grant Morrison steering a big round number celebration, and it’s a fun, all-encompassing look at the history and possibilities of the concept that while relatively self-contained in the context of their larger run still mirrors it in interesting ways.

What always stuck me however was the final montage of future inheritors to the cowl to demonstrate the permanence of its legacy, featuring Terry McGinnis, a reimagining of the 1950s future hero Brane Taylor, and Morrison’s own Batman and Robin of the 853rd century. Sandwiched between the latter two however is a new figure, seen below:

Before getting into the in-depth narrative analysis: that’s such a cool-looking page. David Finch gets his share of criticism, much of it well-earned, but his and Richard Friend’s lovely, art deco-ey future metropolis and the kickass energy of those last two panels, dressed up in Peter Steigerwald’s sickly neon glow presaging FCO Plascencia’s eventual chromatic dominance of Gotham? Does so much to sell the idea that this is a future where a crime-fighting man in a bat suit still makes some kind of aesthetic sense.

The other three pages are homages, even if it’s to Morrison’s own past work: their significance is in the notion that this is (a) Batman as you already know him, brought back for a moment for your nostalgic benefit and to serve the larger themes by his presence. This however doesn’t have that to lean on, and so not only has to construct its own idea of a future Batman from scratch, but relies entirely on how well it’s able to convey that notion. This has to hit recognizable high points and convey an altered context in equal measure, and Morrison’s choices of how to do that - their shorthand of an ‘iconic’ Batman, and the world in which they see such a thing persisting - hold a mirror not only to the run up to that point but the direction it would progress in years to come, and Morrison’s future work beyond that.

First thing’s first, one seemingly minor aspect: this isn’t the last we’d see of Nugothotropolis Megurb. In Morrison’s Action Comics we’d briefly see it again, circa 3030AD and having survived a reboot cycle, as one of the locales of an underground Legion of Superheroes from a corrupted version of their timeline where Universo rules over all.

(Which not only retroactively situates this in time somewhat, but also means its presence may mean things aren’t great. We’ll get back to that.)

More importantly, the main way besides the name and who we’re about to see we know this is still some version of Gotham: everyone’s drugged out. One of the big threads throughout the run - never building to a plot climax in terms of having always been part of the Black Glove or Leviathan’s plans, but always simmering as a piece of the texture of the world - is how Batman’s landscape is inextricably bound up in the intersection of “chemicals and crazy people”, so it makes perfect sense that in years to come the entire population would be floating away on a Soma coma. Not only does it fit with Morrison’s interpretation of Gotham as a place where the citizenry puts up with its assorted horrors “for the sheer buzz”, their past history of psychedelic use and eventual abandonment, and that the run proper would later progress from the Joker pandemic seen earlier in this issue to Doctor Hurt’s more subtly horrific contagious drug addiction, but eventually they would go much further into the idea of a chemically mood-controlled society in their adaptation of Brave New World for Peacock.

Just as significantly? Capitalism still exists. That particular element as part of Bruce Wayne’s horror story would come to the forefront with Batman Incorporated, but even a thousand years into the future, some people are getting by on less than others. Whereas Batman? Lives in the tallest building in the city.

And here’s our guy! Rocking those pointy dracula shoulders as previously portrayed by McKean and Porter in Morrison’s Arkham Asylum and JLA with the edges of the cape likewise curling up, thigh-high boots, segmented armor plating, and as we’ll see later the classic yellow oval bat-symbol. A decent mix of the gothicly over-the-top and reminders that this is still a human being in a costume, that’d probably look more than a bit silly as the standard but viewed from the distance and in the context of fitting a nebulous future aesthetic more than suitable. He’s a Batman who evokes a bit of the 70s era that Morrison so loved (who likewise lived in the heart of Gotham), intimidating and toyetic in equal measure.

It’s not the only option in his wardrobe though: as he gets ready for his latest night out we can see he’s been through at least five other variations of the Batsuit across his own personal tour of duty. Granted these could feasibly be mementos of previous Batmen, but given he has his own futuristic variation on the giant robot dinosaur, it seems likely these are intended to be his as well. Unlike most ‘future’ or ‘alternative’ takes on a superhero who exist as a single defined state of contrast with the main iteration, this is a Batman with history behind him, a Batman who’s reshaped himself with the times in the same way that defines Morrison’s Bruce Wayne. A Batman who’s come back bigger and better, shiny and new. A Batman forced to endure.

Despite that tie to history though, one thing notably lacking in this bat-lair is a sense of horror outside Batman himself. Rather than a retrofitted cave echoing with the screeches of the local population this is a clean, sophisticated environment - there are guard rails for god’s sake, you’d never find one of those under stately Wayne manor even if the cracked stone floors likely deliberately evoke the old homestead. It’s not just posh in the way we might have anticipated from the previous panel, it’s apparently a headquarters that’s 100% trophy room between the suits, the dinosaur, and the mural of the building itself, with the lines extending outward from the roof framing it as a beacon illuminating Nugothotropolis. A belfry after all isn’t just a place bats are known to well, it houses the bells of churches: this place is a cathedral to all things Batman, ready to deploy him into action when trouble rings out in the form of a pleasingly defanged-sounding social weather disturbance.

Just past the halfway point and we have our threat in the Anti-Utopian Army, and on the one hand these aren’t just the bad guys, they’re Bad Guys. There is no level of post-irony or semantic wrangling where THE HATE REVOLUTION refers to the general betterment of humankind. On the other, Morrison would go on to define the classic m.o. of Batman’s rogues gallery as perpetrating “clever, imaginative crimes against the status quo”, and while there’s little doubt whatever’s planned here is much morally superior to laughing fish or turning city streets into gigantic crossword puzzles, in only two panels we’ve been given serious reason to doubt the status quo in question here. The ‘day-in-the-life’ snapshot we’re given is defined by the seams of this society, and Batman, spreading his wings wide, is here to swoop down from the glimmering heights of this world to preserve it from the rot beneath.

The thing is: I don’t know how much Morrison intended this. This final panel is stirring, triumphant, braced with iron determination in the face of unmasked horror to save us when nothing else can. It’s a really good Batman moment! As much as I dissected this state of affairs up above, it’s easy to imagine Morrison intending this as a broadly positive society with the issues highlighted in the first panel as a bit of cheeky texture. In fact I’m pretty sure they must have, because otherwise this is a radical outlier from the celebratory tone of the rest of the issue. But it’s also hard to imagine this page didn’t stick in their mind, not only because they brought back Nugothotropolis for Action Comics in a more plainly dystopian context, but because they reused the central premise here as the framing device of their ‘final’ DC project in Wonder Woman: Earth One Volume 3 with half of the book taking place a millennium in the future as terrorists threaten the social bedrock of the Republic of Harmonia. Except in that 31st century - one replacing this one - the future is truly, meaningfully brighter socially as well as technologically, with the Manly Party rather than attacking an institution with visible flaws solely seeking to reclaim their personal dominance. While their defeat and rehabilitation reaffirms the power and long term utility of Wonder Woman’s ideals in bringing about equity, the very circumstances that necessitate Batman’s continued existence into an equally far future in class divisions, mass psychological turmoil, and social unrest at the same time call into question the cost of justifying him. To have a Batman forever means that while he may endure, may change with the times while never surrendering in the face of evil, he must also struggle and suffer without end, must stand atop the ramparts looking down on us eternally, must exist in a world that NEEDS a Batman.

The promise of the end of Batman #700 is that our hero will be here “No matter when. No matter where. No matter how dark.” It wouldn’t be unfair to call this the thesis of Morrison’s interpretation not just of Batman, but superheroes period. But with Batman Incorporated so close on the horizon where Bruce Wayne’s attempt at redeeming capitalism via his noble guiding hand will end in death and humiliation, soon to be followed by Multiversity exploring what the idea of superheroes lasting forever in perfect stasis really means, and their final round of DC titles in The Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, and presumably the leaked Superman & The Authority crying out for endings to the old ways of things? I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that whatever Morrison thought at the time, much as they may still love these characters and their ability to represent something worthwhile, this one page is a pivot point. It is as plain a foreshadowing as possible of the moment where Morrison’s perspective begins to change from this:

To this: