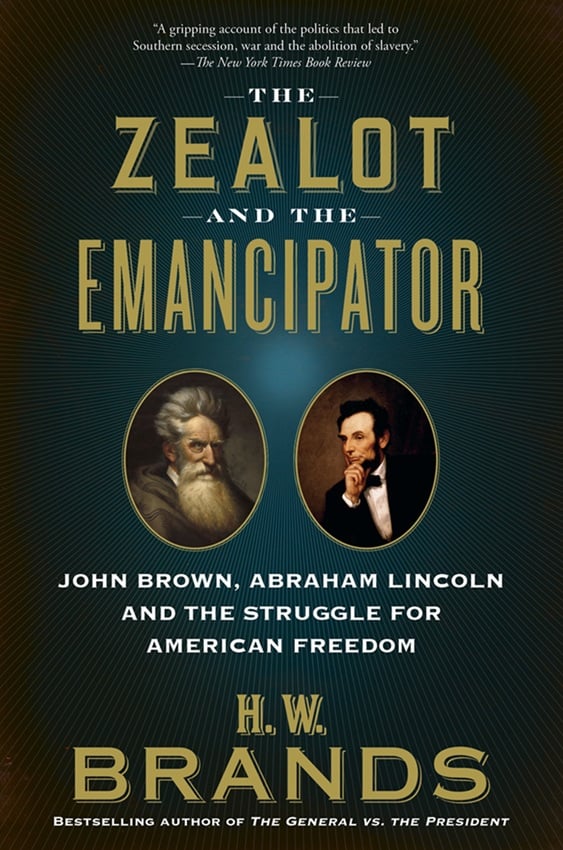

The Zealot and the Emancipator by H.W. Brands

H.W. Brands delivers an epic page-turner with The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle for American Freedom, first published in 2020.

H.W. Brands delivers an epic page-turner with The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle for American Freedom, first published in 2020.

I’ve been wanting to read this book for quite some time ever since John Brown got placed back on my radar while watching Emperor in 2020. The film was about Shields Green, an ex-slave who participated in John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. It came out less than two months before Brands’ book was published.

It’s a known fact that the Compromise of 1850 bought time before the nation fell into war. It wasn’t a matter of if, but when. The Fugitive Slave Act was part of the compromise and let’s just say that it received a negative reaction among abolitionists. Two years later, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, receiving praise from abolitionists. Some say that the first shots of the Civil War were fought during the Pottawatomie Massacre in May 1856 in Kansas Territory. The violence in Kansas followed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, an act that repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Everything would ultimately lead up to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

Brown was of the belief that G-d told him to destroy slavery. That’s why he led followers into Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed the citizens to decide whether they wanted to be a free state or a slave state. Missouri even sent people across the border into Kansas so as to influence the vote.

In Illinois, a one-time congressman and lawyer, Abraham Lincoln, decided to take to politics as a solution for defeating slavery. The irony of Lincoln authoring the Emancipation Proclamation is that he earlier endorsed the principal of the Fugitive Slave Act. Lincoln was aligned with Henry Clay in his beliefs. Upon eulogizing Clay, Lincoln acknowledged that the Kentucky statesman “was, on principle and in feeling, opposed to slavery. And yet, Mr. Clay was the owner of slaves.” It didn’t stop Clay from advocating for Kentucky to emancipate its slaves.

When the Whig Party fell apart, some joined the anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party. However, most members joined the newly formed Republican Party. This was a party that “knowingly took its name from the party of Thomas Jefferson, who had sought and end to slavery while appreciating the difficulty of getting there.”

Flash forward to 1857, Chief Justice Roger Taney waited until after James Buchanan’s election before announcing the Court’s opinion of Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857). What the Court ruled was that enslaved people and their descendants were not citizens and that Congress lacked the power to ban slavery in territories. This decision effectively made the Missouri Compress moot.

John Brown may have been zealous in his attempts to free the slaves but he was far from being some sort of fanatic as has been described. Brands cites testimony from those taken hostage by Brown on the road to Harpers Ferry. Even though he was ultimately sentenced to death, he had an effect on his interrogators. Then-Virginia Governor Henry Wise said “they are themselves mistaken who take him to be a mad man…He is a man of clear head, of courage, fortitude, and simple ingenuousness.” A number of legislators—Senator James Mason (D-VA), Rep. Charles Faulkner (D-VA), and Rep. Clement Vallandigham (D-OH)—were among those to interrogate him with a New York Herald reporter present.

How did Lincoln react to the news from Harper Ferry? He groaned. Interestingly enough, he was touring Kansas and meeting with Republicans. Lincoln told his audience: “John Brown has shown great courage and rare unselfishness.” In seeking a moderate image who stood for the rule of law, Lincoln had to distance himself from Brown’s actions. Talking of Brown’s actions:

“No man, North or South, can approve of violence or crime. It was, as all such attacks must be, futile as far as any effect it might have on the extinction of a great evil.”

At this point, things were looking up for the Republican Party with regards to the 1860 election. What if any impact would Harpers Ferry have on the larger voting populace? As Lincoln eyed the White House, he had to speak with caution and approach with moderation. Brown’s actions didn’t stop abolitionists from viewing Brown as a martyr while the Southerners were angry.

Lincoln’s inaugural address didn’t stop Southern states from seceding from the Union. A few border states stayed on and fought with the Union but even these efforts were not always easy. Once the war moved into 1862, Lincoln would face even more pressure to take action against slavery. In Lincoln’s view, “the war was about the Union, not about slavery, and for him it was.” At the same time, “everyone, including Lincoln, knew slavery was the underlying cause of the sectional division that had produced secession and the war.”

In early 1862, Lincoln explored a proposal in which emancipation would stay with the states but the federal government would fund it. Congress endorsed his efforts but it was more or less dead on arrival. They looked at compensated emancipation as rewarding slaveholders for starting the war.

Lincoln would spend plenty of time over the course of two weeks patiently writing at a telegraph office located at the war department. The only person who really knew what he was doing was Major Thomas Eckert. Not even Frederick Douglass, Horace Greeley or other White House visitors were in the know. Following a cabinet meeting, Lincoln took Secretary of State William Seward’s advice to wait for things to turn on the battlefield. The second Battle of Bull Run was a disaster and even though the Battle of Antietam ended in a draw for the Union, Lincoln decided it was time to publish the Emancipation Proclamation. Come January 1, 1863, all slaves would now and forever be free on American soil, including those states in rebellion.

The book runs 400 pages and effectively serves as a dual biography of two compelling subjects in our nation’s history. It’s fascinating to see the compare and contrast play out in how Brown’s efforts moved Lincoln in a different direction. If you’re looking for a captivating read on both Brown and Lincoln, you can’t go wrong with H.W. Brands’ The Zealot and the Emancipator. Brands shows once again why he is one of the best historians in America.