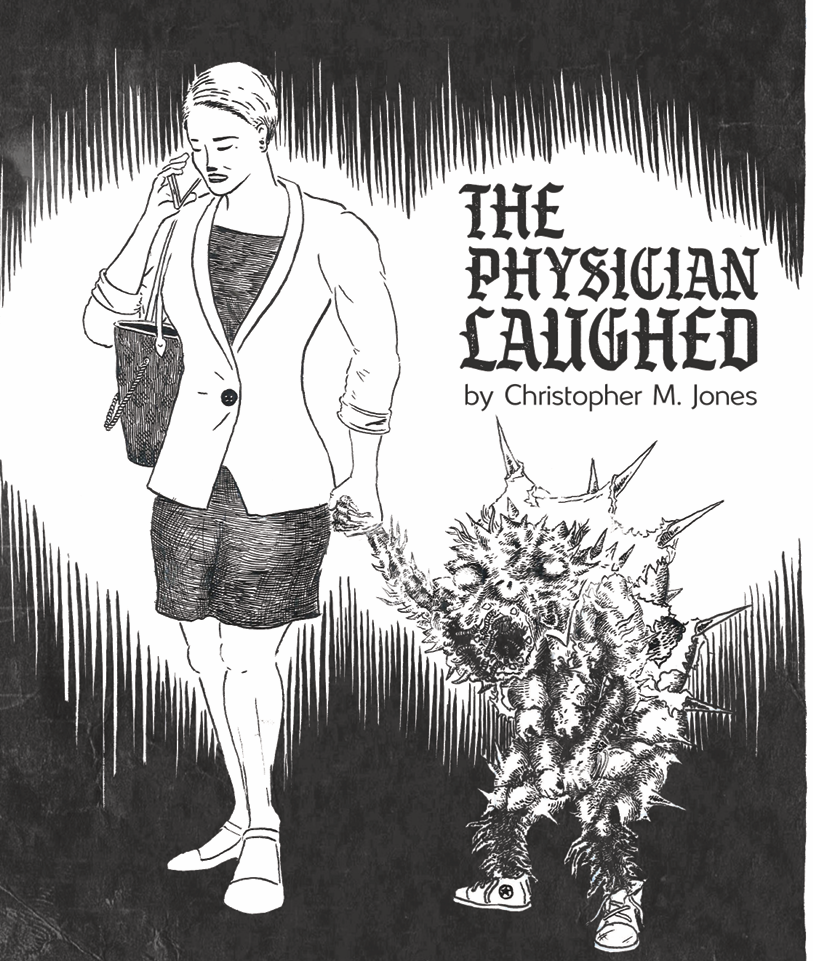

The Physician Laughed

I first met Annette when she brought her son Cody into my office; he had been fussy, complained of headaches, and experienced spasms of vomiting. Fairly ordinary flu symptoms, or so I thought at first: but I became alarmed when I examined his eyes and noticed a slender yet very brittle orange tack beginning to form around the outer rim of his sockets. I asked him to open his mouth and saw that the tips of his teeth were wispy and degenerating into a grass-like texture.

These symptoms weren’t unfamiliar to me. Arthropodia had been making a resurgence over the past generation, and so right out of medical school the entire graduating class of my year had been drilled extensively on what to look out for. Still, broaching the subject could be tricky. Arthropodia, being of extraterrestrial origin, is difficult to spread and tricky to research, and although most sensible parents vaccinated their children anyway, there were no laws obligating insensible parents to follow suit.

“Has he had his shots?” I asked.

“No,” she replied, “we don’t believe in vaccinations.” I was unsurprised: this woman struck me as the type who thought herself exempt from the bindings of human reason. I guessed at the time that she must have been in her late 30s; she was wearing a businesslike amount of makeup and a Chanel suit, or something that could be passed off as Chanel. Her face stayed pinched in an impatient grimace until she turned to her son, whereupon she broke into a clownish smile. “I know he appreciates it.” She grabbed him behind the shoulders and started swinging his arms around as though she were forcing him to imitate a circus ape begging for change. He looked drugged, in mental retreat. “I know he likes that I don’t make him do the pokey hurtys.”

I ground my molars. “Well, I know they aren’t especially fun, but inoculations are important, especially for a boy as young as he is. Would you consider—”

“Aren’t there pills you can just buy at the drugstore? Vitamins and herbs or whatever?” One would be stunned at how many people visit the doctor with a cure for what ails them already in mind.

“Yes, but those aren’t reliable as serious treatments, and many of them are distributed without license or regulation. Perhaps—”

“I just came here as kind of a last resort, you know? Big Pharma’s a scam anyway. He just needs something to make his tummy stop hurting, he doesn’t need all those nasty chemicals messing with his metabolism.”

I began scribbling on my prescription pad, already aching to be rid of this woman. “I’ll write you some—”

“Giving him autism.”

“I’ll write you a prescription for some antibiotics. If this is just a flu they should help tremendously with his nausea, and I promise they won’t harm his physical development.”

I handed her the sheet, wondering if my sarcasm had penetrated. She seemed unaware that anything had been stated at all. “Please see me again if Cody hasn’t improved in a week’s time.”

She nodded, took her son by the hand and left my office. I sat at my computer and disinterestedly fiddled with some documents for a few minutes when I heard a knock on my door. It was Darryl, my receptionist.

“Hey doc,” he said, a puzzled grin stretching across his face. “Ms. Annette Coleman would, uh, like to know if you’re available for dinner on Thursday evening.”

Assenting to this woman’s pursuit felt like a mistake even as I texted her to confirm plans, and our first dinner turned out, unsurprisingly, to be awkward, grating and ridiculous. We had nothing to talk about and little in the way of physical chemistry. I tend to find at least a measure of charm and insight in all my partners, even the ones I can’t relate to; everyone has a story, and that story is always as compelling as the effort you put into deciphering it.

But with Annette I found that this extension was impossible to make. Her mind seemed to be encased in an indestructible seal of vacuity. No matter what topic of conversation I came up with she would always round it back to complain about coworkers or her son’s teachers, or else she would just start listing TV shows she was watching. I couldn’t chalk this up to first-date jitters, because she was composed to the point of being steely; there simply seemed to be a genuine lack of stimulus in her inner world. This isn’t the same thing as stupidity, but it can be just as frustrating to contend with.

It was a dreadful evening, and when I asked if she wanted to come back to my house for dessert it was largely with the intent of creating a sharp, definite break in the night so I could go home by myself and be done with it all. I was surprised when she responded with earnest enthusiasm.

Sex is boring, as a rule; even good sex is boring. Anything done in pursuit of an identical result in each instance becomes boring as time and knowledge accumulate. So it was with Annette, but what I experienced with her wasn’t that benign, almost pleasant dullness that frequently comes with lackluster chemistry. She resisted foreplay, dismissing my polite efforts to tongue her down. She would occasionally respond to me with a breathy gasp but seemed largely disengaged, sometimes even looking visibly frustrated. We ended without either of us climaxing; I wrestled my pants back on, then sat on the bed with my palms folded and looked at the ceiling.

Annette started calling someone. “Hi, Cody.” She used her baby voice. I looked at my clock and observed in amazement that it was only 9:30. It felt like hours and hours should have passed between dinner and now, instead of just one. I eavesdropped; whenever Cody responded his sentences would begin with a click, like the fluttering of roach wings, and would continue with a moaning intonation that didn’t strike me as normal.

“How’s Cody?” I asked when she hung up.

“Oh, better. Still a little sick.”

Her tone was pleasantly evasive. She was checking her Instagram feed, not looking at me. “Well, I definitely want to see him again if it seems like he isn’t improving fast enough.” Putting on my mannered Doctor Voice post-coitus made me feel absurd, but it was the only thing I could think to say.

“Sure.”

A small silence ensued. She remained checking her phone as I resumed gazing into nothingness. Finally, I got up. “I’m going to watch some TV, do you—”

“No, I’m fine.”

“Alright.” I went into the living room and started watching a movie, after which I fell asleep on the couch. By some point in the early morning she had silently excused herself from my house, but I still didn’t want to sleep in my room. It would have felt like disturbing a pharaoh’s tomb to go back in there, an invitation to a curse.

I assumed that the evening would end up as just another entry in life’s seemingly endless collective ledger of contemptible one-night stands, but against all expectations Annette sent me a text two days later asking if I would like to meet her to go see a movie. I do not know why I agreed; some part of this ludicrous courtship must have appealed to my vanity. The movie was bad, and its aftermath was much as it had been on the previous occasion. She asked to see me several more times, and several more times I agreed. It was all a dreary, emotionally deadening waste of time that I could not seem to find any strength to say no to. Whenever we had sex I would hint that she should bring Cody in to see me, and each time she would agree in a noncommittal manner and the subject would wilt away.

One day we happened to have the same afternoon off and decided to meet for lunch. As we started walking back to her house we passed Cody’s school during recess. She jogged up to the fence and waved to him, and he trundled over. The arthropodia had become acute; his eyes were glassy and grey, and an igneous webbing had started to form between his fingers. When he opened his mouth to say hello at the prompting of his mother saliva spilled from between his teeth, which had become soft and billowy. I could barely cloak a disgusted scowl as I waved to him in response. We continued our stroll; I was incredibly troubled by his condition. Finally I suggested we stop to get coffee, and once we had sat down with our drinks I broached the subject of Cody’s sickness in earnest.

“So, I can’t help but wonder why you haven’t brought Cody back in for a follow-up appointment.”

Annette looked perplexed. “What do you mean?”

“Well, he’s obviously…he doesn’t look well. Don’t his growths concern you? Haven’t the other children commented on it?”

She seemed vexed by my questions, even offended. “Well, if they have then Cody hasn’t said anything to me. And anyway, these things kind of go away by themselves, right?”

I rubbed my forehead, stared into my coffee as if to drown; I tried to explain the disease to her like a patient Facebook friend might, like a Vox article. “Listen: when we drove the Syggorith back to their home world, a lot of people assumed that their biological weapons and agricultural sabotage had been scourged from the Earth, and that things like arthropodia were ‘cured’ and we’d have no more need to worry about them. That couldn’t be further from the truth. While we’ve developed powerful medical defenses against the illness, it can still—”

I looked up and noticed that she was shaking her head. “You medical people will say whatever it takes to push your pills on the rest of us. First you guys said you needed to touch a Syggorith to get a disease from it, now you’re saying arthropodia is making a comeback even though they’ve all been gone for like, 25 years. Which is it?!”

There was so much to explain, and such barren soil for this explanation to take root in. I tried to remain measured. “Hypotheses change. Diseases mutate. What we’re dealing with now is not, per se, the same type of arthropodia we’ve had to exterminate in the previous decades, but it is still very much a threat to human well-being. It would do to at least bring him in for a vaccination. Couldn’t you agree to that?”

“Those vaccines kill, and they’ve killed a hell of a lot more people recently than the disease they’re supposed to cure! What about those kids in Pensacola that all went retarded and died because of your vaccines? When’s the last time space fever did that to anyone?”

I couldn’t conceal my irritation any longer. “Those children were known to be allergic to the vaccine. Their family was warned about a possible reaction. Less than one in twenty thousand people are allergic, and it’s an easy thing to check for. If parents like you would simply perform their due diligence--”

“Don’t you people go on and on about how it isn’t even contagious? Like you can’t even get it by breathing it or touching someone who has it? So is it a problem or isn’t it? Don’t blame me for something you ‘doctors’ can’t even seem to wrap your heads around yourselves.”

I couldn’t restrain myself anymore: “Cody is a monster, Annette. He needs medical help.”

I could see her boiling, just barely resisting the urge to throw her drink in my face. “Fuck you,” she spat. “Fuck you, you stupid asshole know-it-all…crook.” She grabbed her coat and walked out of the cafe. I drank the rest of my coffee in one big gulp and went to the bathroom to take a long, burning shit.

Life after our “breakup,” as it were, continued much as it had before I had made Annette and Cody’s acquaintance. Flu season had passed, and the office had turned quiet. I spent most of my days diagnosing children with allergies and playing Words with Friends with Darryl.

A few weeks later I ran into the two of them on the street. Annette greeted me with a sheepish “hi” before turning to her child and saying, “You say ‘hi’ too, Cody.”

Cody had become unrecognizable as a human being. His skin had turned into a brackish, rust-colored carapace with only thin, weak tufts of hair able to wisp out of the insets of his shelled scalp. His eyes had lost all color, and the remains of a windbreaker hung in tatters off his back; his flesh had become too sharp for him to be able to wear soft clothing. When he opened his craw to greet me the smell of an abattoir came billowing out; as I held my fingers over my mouth and nose I observed that his teeth seemed to have been entirely replaced by semi-sentient parasitic worms, each trying to wriggle desperately away from the burning stimulus the oxygen coming into his mouth must have created for them. His “hi” was a low, creaking hiss. I felt my gorge rising and turned my attention away from Cody to keep from vomiting. Annette looked sorrowful, almost repentant.

“Cody hasn’t been doing too well,” she said regretfully. “I took him to another doctor, and they told me at this stage his condition is irreversible.” She wiped a tear away. “I just don’t know what I could have done.”

The inanity of it all incensed me even through the wall of horror I felt towards the boy, but I couldn’t bring myself to come down hard on her. “Well, I’m sure you can give him a lovely, comfortable life with what time he has left.” It didn’t feel rude or cruel to speak past Cody; I wasn’t sure he was even capable of processing sound in a typical human capacity at this point.

“Yes.” She paused and looked up at me. “Look, I do feel pretty awful about how I reacted last time we met. I think there might have been some merit to what you were talking about, and…” She let the silence linger. “I can’t really leave the house much with Cody the way he is, and I was wondering if you might want to come by for coffee and just talk a little bit. Or.” She found it in herself to smile with a bit of mischief. “Or other things too.”

Clamping my lips closed to keep bile from running out of my mouth, I nodded my head in assent and mustered a smile.

I went to her house the next afternoon. When she wouldn’t answer the door, I texted her; when I didn’t receive a reply after five minutes, I decided to scoop up the housekey I correctly predicted would be under her doormat and come in. Her home was decorated with a demure affectation which revealed a gauche sensibility in its clumsiness: lots of pinks and beiges, lots of insensibly placed rugs.

“Annette?”

The name was swallowed up by the walls. I walked into the living room, called again, peered around corners: still nothing. After a period of silence, I went to the foot of her staircase and from there I could hear a barely perceptible rustling upstairs. As I ascended the stairs the rustling became louder, though still muffled. I found her bedroom and opened the door.

Every cubit of the room was drenched in a perfect deep crimson of dried blood. The stink would have sent me scrambling away were I not transfixed by the grotesque vision unfolding in front of me. Annette’s body was on the bed, open like a suitcase from her scalp to the tips of her feet; her eyes were jiggling perpendicularly to each other in her sockets, as if tracking two flies buzzing on opposite sides of the room. Cody was hanging from the ceiling, one of his claws dug into the plaster and the other fastening a rope of entrails into a knot around the ceiling fan. It appeared that he was trying to make some kind of structure out of her organs, her intestines and colon tied upon and festooned from bedpost and wardrobe and windowsill into the shape of what seemed to be a shrine of sorts hovering several feet above the ground. I could see several smaller organs, such as a cochlea and bladder, wrapped together into a tiny ziggurat within this structure, fastened to the larger gore-edifice by what appeared to be stomach lining. As he finished tying the knot around the fan, Cody pivoted his face back over the bed as if to vomit; an avalanche of worms cascaded from his maw and began rooting through Annette’s open body for unused parts. I stayed in the room long enough to see them wrap around a shinbone, pull it away from its socket with a slippery crack, and then slither up the wall with it at a speed I found shocking given their small size and lack of tactile force. If Cody saw me or detected my presence, I clearly wasn’t his concern; his focus was this project, this tribute. Still, I closed the door quietly and made my way down the stairs at an urgent pace.

In the kitchen I found some lighter fluid under the sink, and a trigger torch next to a knife set. I shook the fluid onto the hallway carpets in a judicious manner, as if seasoning a stew, then set fire to them and quickly left the house, dialing for a car when I had made it a few blocks away. As I was putting my phone back into my pocket, I noticed a slight but very hard orange tack developing between my thumb and forefinger.

A white Subaru pulled up moments later and my driver, whom the app told me was named Joachim, waved and smiled ingratiatingly. I got in.

“How are you boss?”

“I’m good, just fine today. Please take me to the hospital.”

Joachim narrowed his eyes and looked at me with what felt like genuine concern. “Everything OK, boss?”

“Yes.” I chuckled. “Yeah, I think I’ll be fine. I think I caught it just in time.”

“OK boss. St. Andrew’s yes?”

“No, let’s go to County Medical. The wait tends to be a little bit easier there.”