Make Some Noise for Manila

The Philippines offers a glimmer of hope that Southeast Asia's scam industry isn’t destined for a future of unchecked growth.

“So we can go to the torture room now,” my guide said as he closed the door to the children’s cafeteria and pointed down the hallway to the said torture chamber.

It may sound strange to have a kids café located on the same floor as a torture chamber (don’t worry, the chamber’s no longer in use). But the contradiction is at the heart of a larger transformation quietly under way in the Philippines as the country seeks to shut down, seize and repurpose dozens of properties that used to house violent cyber-scam operations.

My guide was Marvin de la Paz, an officer of the Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Commission, the government agency tasked with cleaning up the scam compounds, better known in the Philippines as “POGOs.” That’s short for Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators – a fig leaf of a term used to give them a patina of legitimacy as licensed internet casinos. In reality, the games were rigged and the real money came from outright fraud operations that POGO bosses mixed with a bevy of other abuses, ranging from prostitution and human trafficking to money laundering, kidnappings and murder. Hence the torture chamber inside the former POGO we toured in Manila, where blood stains were still visible on the walls.

These days, however, the building is getting a second life under the PAOCC, which coordinated a police raid in October 2023 and discovered 731 workers who toiled inside, many of them forced laborers in online scamming or prostitution (the building featured a dehumanizing “aquarium” for prostitution, an area where Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean and Filipino women waited be selected by customers). Since the raid, the PAOCC has turned the building into its headquarters, where it plans its next moves against other POGOs and hosts a cafeteria to feed malnourished children. PAOCC’s executive director, Gilberto DC Cruz, told me that his goal is simple: Eliminate all the scam compounds that have popped up across the Philippines in recent years, seize the properties and turn them into positive social infrastructure, like military bases and universities.

To fulfill that vision, Cruz, age 60, is purposefully hiring young people like de la Paz who are fired up by the notion of making the Philippines a better place to live. “I want principled people. I want people who think for the betterment of this country,” Cruz told me. And it’s not just his country that will be affected; the PAOCC and Australian Federal Police recently traced thousands of online romance scams to victims in Australia. That’s just one of many nations affected by these scam operations, which in recent years started to take on industrial-scale proportions.

To get a better sense of the size of these operations, we drove to Bamban, a small rural community about two hours’ drive north of metro Manila. The town made international headlines when a March 13, 2024 raid on a massive POGO there exposed links between the online fraud factory and the local mayor, Alice Guo; a flood of news coverage followed, culminating in Congressional hearings and an executive order by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to ban POGOs. Videos of gruesome torture from inside the Bamban facility aired at a July 2024 hearing with House lawmakers helped put a face on the industry and show what really goes on inside.

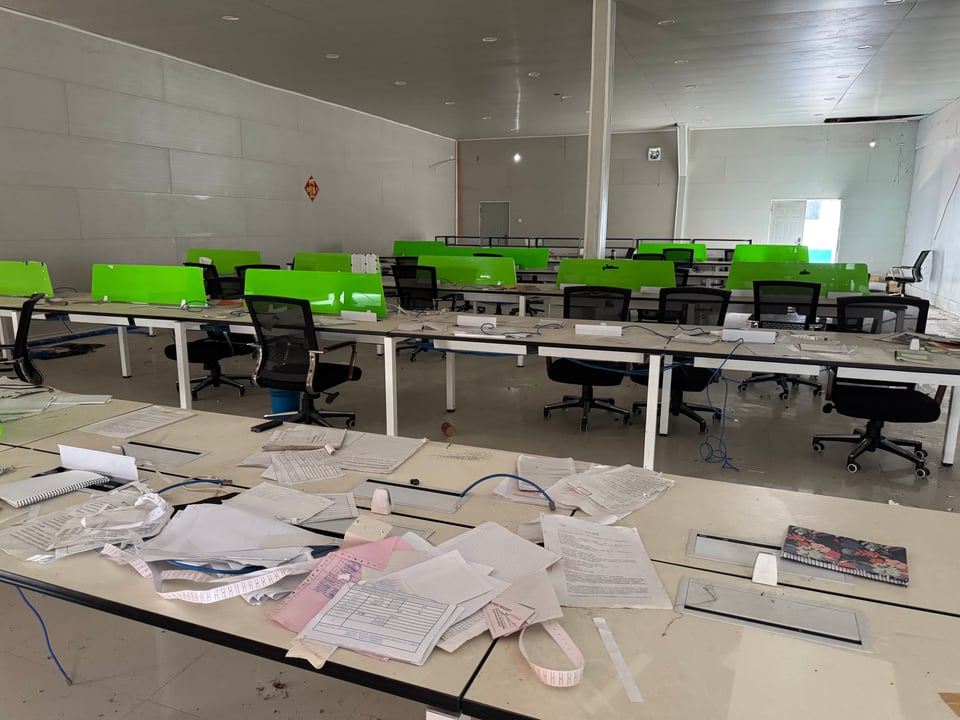

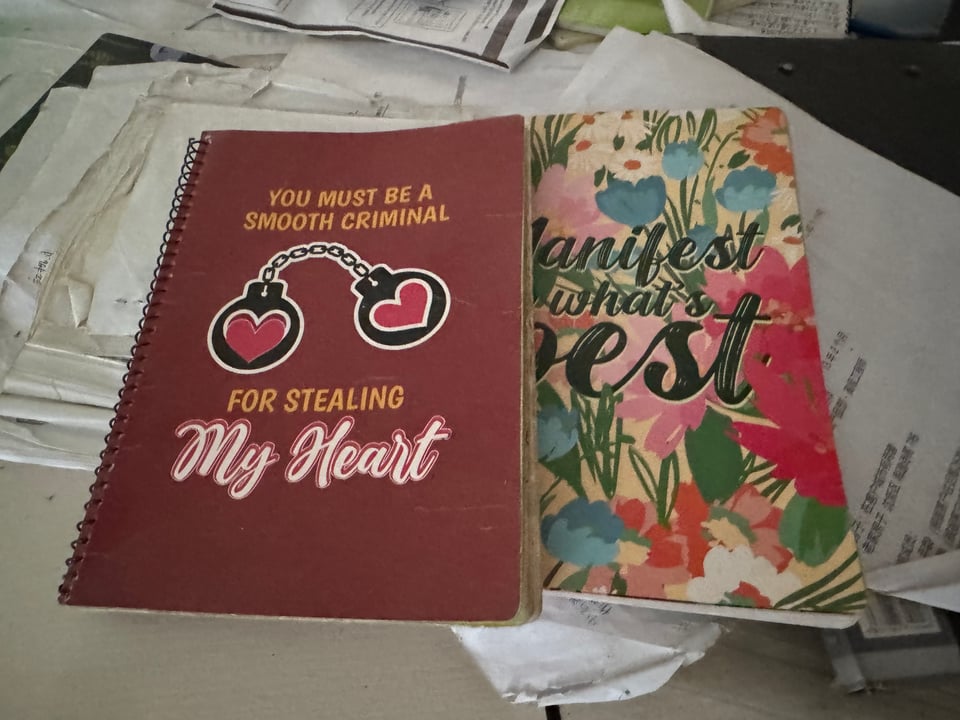

Walking around the 10-hectacre Bamban POGO, officially known as the Zun Yuan Technology complex, I couldn’t get over how large it was. Not just large, but brazen; its sponsors invested in luxury villas for bosses and underground tunnels for escape, an Olympic-size swimming pool and dozens of buildings to house large-scale office space for scam operations and workers’ dormitories. Scam scripts and notebooks are still scattered on tables inside the raided scam company offices, along with all the accoutrements, like a gong to ring-in a big win when a fraud victim loses a lot of money. You get the idea – fraud on a massive scale, unless someone shuts the place down.

“If you had the gall to build something like Bamban, you knew that you were there for the long haul. So you thought that it would never end. But it did,” Winston Casio, the PAOCC’s spokesperson, told me during a meeting in Manila.

The PAOCC has now supported 18 such raids since May 2023, a sharp contrast with the largely unchecked growth of scam compounds in Cambodia and the hum of construction I saw on the Thai-Myanmar border during my visit there in March. It’s a glimmer of hope that the fraud industry in Southeast Asia isn’t destined for a future of unchecked growth; where there is political will, there is a way to tackle this problem, as the Philippines has started to do.

Before leaving Manila, I asked Casio what his agency needs from the international community to keep the winning streak going. The answer surprised me; I expected him to say financial support or training. Sure, training would help, Casio said, but “more than the training, it’s the noise. We need the noise back.” That is, more people talking about and caring about this problem to keep the pressure on elected leaders to keep fighting the spread of organized crime: “We need the help of the international community to remind the general public it’s not yet over,” Casio said.

I hope to do my part by making some noise in The Big Trace. Thanks for taking the time to read a bit about the POACC’s important work, and for your interest in my forthcoming book on this subject. Till my next dispatch, thanks for reading and please make some noise by sharing this newsletter with others who may be interested.