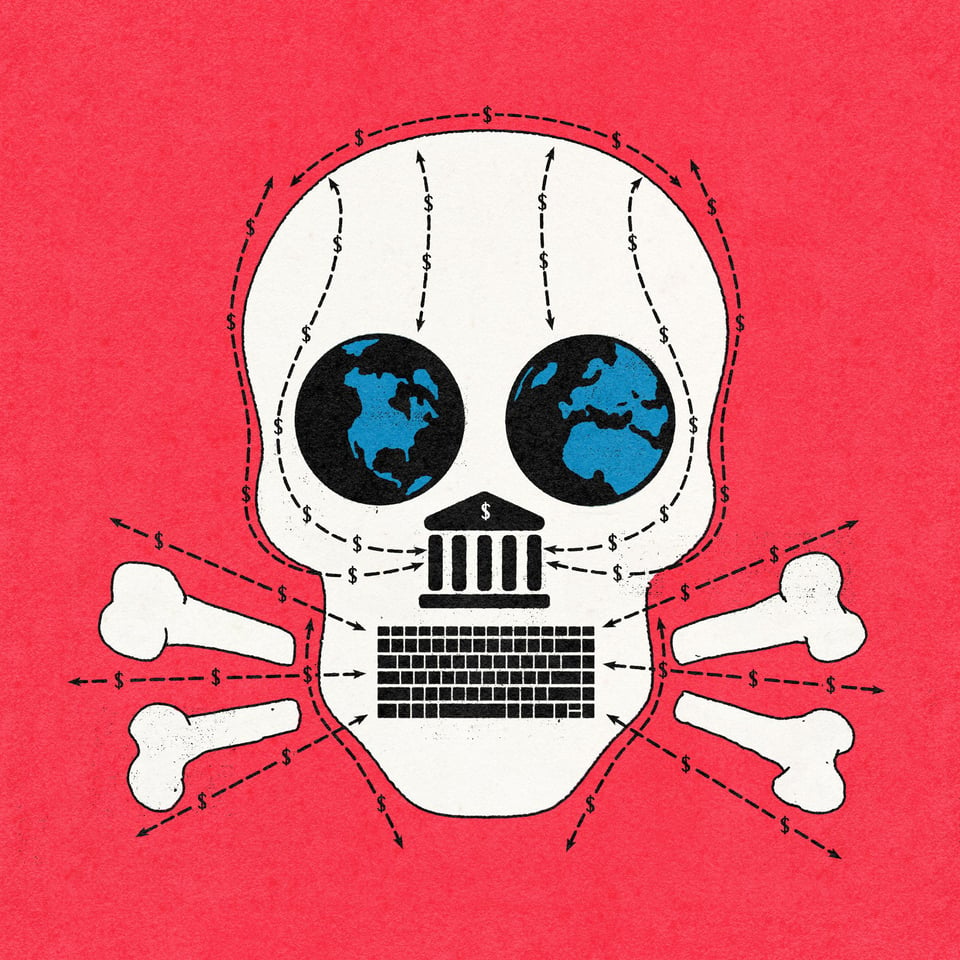

Banks' Pig-Butchering Scam Problem

It's not just crypto. Foreign scammers are also using U.S. banks to fleece Americans.

If you’ve been following the rise of Southeast Asia’s scam centers, you’ve undoubtedly heard the phrase “industrial-scale” used to describe these operations. I can attest from multiple visits to the Thai-Myanmar border and Cambodia that online fraud has indeed become an industry of its own there, with entire compounds that have been purpose-built to house online fraud operations staffed by thousands of willing and unwilling laborers.

But no industry exists in a vacuum. Every trade, licit or illicit, relies on its suppliers and vendors to accomplish its goals and the cyber-fraud industry is no different. In a new article for ProPublica, I dove into what is arguably the most important parallel industry that’s grown alongside Asia’s scam centers – money laundering operations known in Chinese slang as “motorcades” – and the tricks they use to access the American banking system.

Why are Southeast Asia’s cybercriminal networks targeting banks? The typical consumer doesn’t own cryptocurrencies and many pig-butchering scams still unfold with a fraud target tapping a traditional bank account to wire dollars to swindlers, who receive the funds in their own accounts, then convert them into crypto to move across borders. Later in the process, the scammers will typically transfer the stolen crypto back into standard currency and banks again may be utilized to facilitate the movement of dirty funds out of the cryptosphere.

Bank accounts are so crucial to this process that a thriving international black market has developed to rent bank accounts for fraud. Motorcade advertisements on Telegram channels offer advantages such as first-hand control of bank accounts that can be used to send and receive funds. That gives banks a crucial, and not always welcome, role as gatekeepers to the financial system. Yet from the U.S. to Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong, some of the biggest banks in the world have failed to prevent motorcades from opening accounts or engaging in money laundering activities. (You can read the banks’ replies to my comment requests here, and Telegram’s replies here).

Once motorcades secure bank accounts, they can be incredibly efficient at moving stolen funds overseas, frustrating consumers’ efforts to try to reverse fraudulent wires or the efforts of law enforcement to freeze and seize stolen funds. I followed the money trail for a New Jersey fraud victim named Kevin; it quickly led me overseas, with 10 intermediary U.S. bank accounts that siphoned $716,000 of his life savings through fraudulent wires and another account in the Bahamas that was later used to convert his stolen funds into U.S. Dollar Tether. The USDT was then distributed to scammers in Southeast Asia.

But, in a stunning plot twist, Kevin was able to recover a portion of his stolen funds. Read the story to find out the surprising events that unfolded when Kevin sued the shell companies that scammers used to defraud him.

Meanwhile, in Cambodia …

By all appearances, Kevin’s fraudsters were based in Cambodia, where online fraud is now well-documented to be a multi-billion dollar industry. A new report published today by Amnesty International sheds light on the human rights abuses going on inside Cambodia’s scam compounds, and I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to share it with you.

Amnesty researchers painstakingly documented 53 confirmed scam compounds located in Cambodia, plus another 45 locations that had a range of security features like high walls, cameras and security guards, suggesting that they may also be used for scamming operations. Some were repurposed real-estate that was turned into fortified scam compounds, while others appeared to have been specifically built to confine people.

Additionally, Amnesty interviewed 58 survivors of human trafficking who were tricked into working inside 31 different scam compounds across 16 towns and cities in Cambodia. Their testimonies not only confirmed the gruesome torture and abuse that goes on inside the country’s many scam centers, but also the Cambodian government’s failure to effectively investigate and prosecute these human rights abuses. Amnesty said that the Cambodian government “allows slavery and torture to flourish inside hellish scamming compounds” and I’ve seen nothing in my reporting on this problem to contradict that conclusion.

One other aspect of Amnesty’s research also caught my eye. At a press conference in Bangkok today, Amnesty International’s Regional Research Director, Montse Ferrer, described how a group of individuals trafficked to one scam compound had photos taken of their faces. Why? “Presumably to open bank accounts,” Ferrer said.