Issue 11: Winter is Done, Welcome to Summer!

Our pace of publication slowed down this past year; as with everyone else, we were tired. As the seasons shift and the pollen counts increase, let's take a moment to look at some of the summative work that our students put out this year. Our students do amazing things, and it's worth always remembering that fact when we're feeling tired. Enabling our students to do amazing things is why we're here, right?

Discovering Oneself in the Study of History

Lori Jones (Sessional Instructor, Department of History) and Augatnaaq Eccles, (4th Year Bachelor of Arts Honours Major in History)

LJ: As historians – researchers, teachers, and students alike – we are often challenged to justify the value of our discipline. What’s the point of being stuck in the past, we are asked, when STEM subjects are the future of employment, funding, and indeed our very lives. The past is a foreign country, we are reminded, and we could better spend our time fixing the problems of the present than having our heads stuck in bygone decades and centuries. But, what if the concerns of the present exist or have been exacerbated because of our lack of knowledge, or lack of consideration, of what transpired in the past?

One of the big take-aways from the course that I offered this Winter term – HIST4806B, Global and Transnational History: Diseases Without Borders – is that although the pathogens and circumstances change, human beings have, as a whole, tended to respond to epidemics and pandemics in much the same way across time and space. To varying degrees and just like COVID-19, historical pandemics, epidemics, and disease outbreaks have been characterized by stigmatization and divisiveness, searches for explanations and dodgy treatment recommendations, isolation and protest. Having lived through their own recent pandemic, students remarked that they felt much better able to connect to and sympathize with people’s experiences with disease in the past. In this case, the present allowed the past to make more sense, to make it seem relatable, as it were. For their final research projects, I gave students a lot of latitude: they could choose any disease, any time period, and any geographical region that piqued their interest. They could also present their projects in whatever format best suited their talents and interests: traditional essay, podcast, blog, video, digital exhibit, etc. The range of topics and themes was, as expected, rather broad, stretching from 19th century “Progressive Era” associations between immigrants and disease (and attempts to control both); to sexually transmitted diseases in times of war; to the politics and economics of corporate/philanthropic disease mitigation strategies; to the intertwined nature of poor relief and vaccination policies (and resistance to both); to a culturally appropriate exploration of malaria in Africa. For one student, however, the final research project unexpectedly turned into an at times difficult journey of historical self-discovery that unearthed long-suppressed memories of her family and community. Her story follows, as does a link to the results of her final research project: a handmade parka she made to commemorate Inuit experiences in tuberculosis sanatoriums.

AE: When I had started this project, I knew I wanted to focus on tuberculosis sanatoriums and their effects on Inuit communities. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Inuit who were diagnosed with tuberculosis were sent away to tuberculosis sanatoriums in southern Canada in an attempt to combat the disease, which had been prevalent in the Arctic since the 1920s. The forced journey of patients to the southern sanatoriums was abrupt and traumatic, with many unilingual Inuit unsure of where they were going, why they were forced to leave their homes, their families, and friends, or even how long they would be gone. Most Inuit patients remained in the sanatoriums for two and a half years, but some stayed for six years; some never made it home again.

I had first learned about tuberculosis sanatoriums during my previous studies at Nunavut Sivuniksavut (an Inuit studies college program for Inuit beneficiaries); it was at that time that I first learned that my anaanatsiaq (grandmother), one of my aunts, and an uncle had all been sent away to a sanatorium in Manitoba. For my final project for HIST 4806B I decided to dive deeper into this history by going through letters written by Inuit patients that were sent to the Department of Northern Affairs’ Eskimology division and recorded in the Eskimo Correspondence Records. I obtained access to these letters through APTN and Library and Archives Canada.

What I did not expect to find while going through these records were letters written by my own family members. I also discovered letters written by other family members of whose time spent in sanatoriums I had no prior knowledge. It was through these letters that I learned about the devastating consequences sanatoriums had on Inuit families, including my own. I discussed these unearthed letters with my family and found out that Inuit families were often forced to take in children whose mothers had been sent away for treatment, since their fathers had to hunt and work. This had been the case not only for some of my grandmother’s children, but also her siblings. Often when mothers returned after being away for two to six years, their children had no memory of knowledge of who their biological parents were. In many cases, the children could not be returned to their parents; even when they were, their bonds were forever altered. I also discovered that many survivors who were unable to speak English ensured that their own children learned English (and sometimes only English), so that they would never have to endure what their parents had gone through.

I decided to represent the information I had discovered by creating a parka using my anaanatsiaq’s pattern. I also wanted to add designs using techniques common to Inuit wall hangings to represent the art that Inuit patients created to provide for themselves while at the sanatoriums. While I learned so much through this project, it was also very difficult to hear about the hardships that Inuit went through: their loss of family; starvation, not only of Inuit at sanatoriums but also their families back home who no longer had a hunter or provider; and the frequent mentions of abuse that occurred. However, this information gave me an entirely new understanding not only of my own family’s dynamics, but also that of my wider community, and of all Inuit across Inuit Nunangat who were affected in one way or another by tuberculosis sanatoriums. It also motivated me to do everything I could to accurately and respectfully share this history to represent the survivors and their families.

Click here for the link to my final project, the parka that I created.

Some Graduate Projects

Danielle Mahon has been working on how oral histories and public history can intersect when these are digitized. Mahon's final project created a historical audio walking tour and critical reflection. Mahon writes,

My MRE reflects upon the transformations in methodological approaches resulting from research relationships during the design of Walking Africville, a historical audio tour of 1950s and 1960s Africville that takes place in Africville Park, NS. What began as an institutional collaborative partnership with the Africville Museum transitioned into a relationship of co-production through a series of intimate encounters with a former resident of Africville. Intimacy as research praxis reframes academic understanding of difficult histories by investigating lived experience as a series of difficult conversations around engagement, historical trauma, memory, embodiment, and place-based storytelling.

In the final analysis, Mahon argues that:

Intimacy propels researchers to achieve a deeper engagement with the past that connects the significance of individual and collective memory to historical events. Co-production questions traditional research practice by reconsidering not only how histories are told but identifying what knowledge systems are valued and exploring the ways in which histories are experienced differently.

(I'm cheating here; I also write The DHCU Irregular for the DH program, and last week in that newsletter I shared two projects that Regan Brown and Jaime Simons created for their MREs in that newsletter. So, a little cut-n-paste later, I reproduce that text below because, well, these were cool projects too.)

Regan Brown developed a Minecraft mod to allow for an immersive engagement with one of the most traumatic events ever to befall our city, the Great Fire of 1900. What, you’ve never heard of the Great Fire? That is precisely Brown’s point: “perhaps there was a deliberate choice to forget the history of fire and the devastation it brought upon an emerging capital city as it sought to establish itself at the turn of the century.” Structuring the game around archival evidence and contemporary narratives published in the newspapers, Brown seeks to re-acquaint us with the political and social consequences of the Fire through the immersive medium of a game. But what makes the project stand out is when Brown reminds us,

The digital reconstruction of disaster is an ethical maze; on one hand, it is an opportunity to empathize and connect with the past in a new way but on the other hand, it is a disproportionately playful approach to a somber topic. This uncertainty presents a challenge for the discipline of history to assert an ethical framework of our own that applies beyond traditional research and presentation practices.

From Brown's Game Design Document:

The player will begin the game in their editor’s office at the Ottawa Citizen building and then leave to report on the fire. They will be given a starting objective intended to familiarize them with the map, but they are not required to complete it. The player will be able to explore the open world at-will, find as many or as few stories as they wish, and return to their editor’s office any time. Though the game can end upon returning to the editor’s office with a story to file, players will be given the option to continue.

Next, Jaime Simons. In this project, Jaime Simons similarly approaches a forgotten element of our region’s past: the Ottawa River’s use as a piece of infastructure, and the ‘steamboat imperialism’ that this transformation of the river permitted. The project “uses sound and performance theory to engage with the history of steamboat imperialism on the Ottawa River”. A river branches, braids, overflows its banks, dries to a trickle; a river is a kind of fractal. Where does the river begin? We can draw a line on the map, but it doesn’t really capture that reality. Similarly, Simons writes,

Some historians may say that we use archives and their sources to tell a history ‘straightly,’ performance theory echoes Hans Kellner’s need to tell the story crookedly. ‘Crookedly’ is not meant in the pejorative sense, but instead means taking history and flipping it sideways, to dive deeper into it and offer new ways of seeing the material. It echoes the Digital Humanities concept of ‘deformance’ (a combination of ‘deform’ and ‘performance’) which uses sound to defamiliarize visual material and offer different properly, reading with or against the grain to reveal the ‘true’ history. The idea that history can be ‘true,’ in that there is only one version and that the end result will always be the same, is the antithesis of performance theory.

Simons’ project creates an EP that remixes found sounds into a multi-layered sonic experience; the repetition of certain elements plays with memory and forgetting and storytelling. Listen for yourself here.

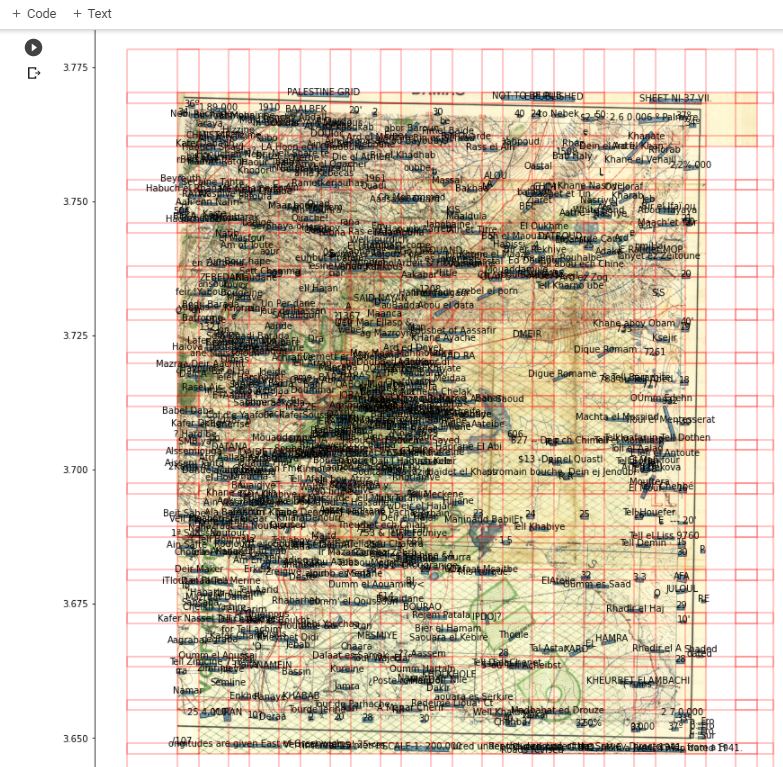

And now for something completely different. The final project we wanted to share was Jeff Blackadar's work on 'automated methods to collect historical information from LIDAR images and maps.' Blackadar's MRE contextualizes work he has published in collaboration with archaeologists in the US and elsewhere to use artificial intelligence to grab historical information from different kinds of images, including maps. One of the interesting side effects about this method Jeff's developed, in terms of maps, is that the annotations can be geolocated (made to appear in their correct location). This will greatly enhance historical geographic information systems!

It's sunny.

Close your computer. Go outside. Enjoy the summer which seems finally to have arrived. See you in the Fall!

SG on behalf of the Communications Committee

Via

Via