Vittrup Man, his life and times

There's been a flurry of excellent and interesting aDNA papers published recently, and I'm still catching up after being in the field... I want to highlight one of the papers that caught my eye because it's such an outstanding example of mixed-methods and because it's emphatically an archaeological paper that makes (great) use of genetic data (among many other types of biomolecular information).

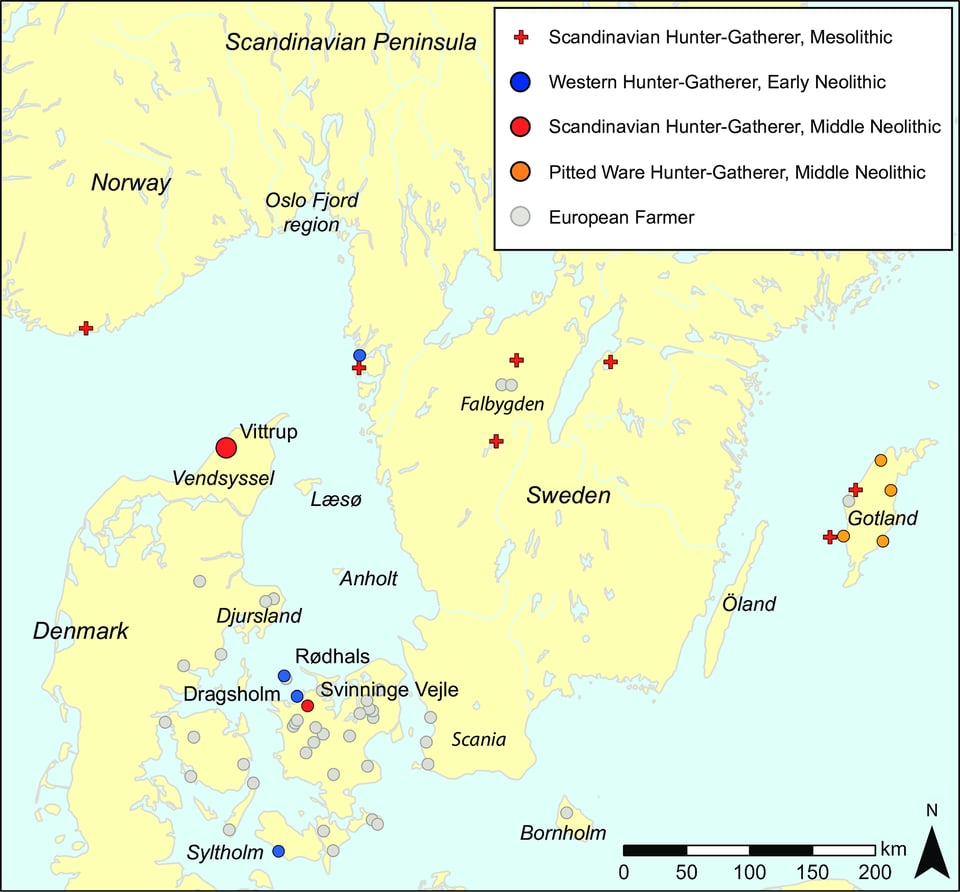

Andreas Fischer and colleagues have done a really comprehensive analysis of some fragmented bones recovered from a bog in Vittrup (near the tip of Jutland, the Danish peninsula).1 The bones--dating to the late fourth millennium BC (the local Middle Neolithic)--had been flagged because an earlier aDNA study had identified them as coming from a person with a distinctly different genetic lineage than most of their contemporaries - one linked more to northern or eastern hunter-fisher-gatherer peoples than to central European people.

Location of Vittrup with other genetically sequenced individuals in southern Scandinavia from different genetic clusters (Fischer et al. 2024, Fig 2).

Location of Vittrup with other genetically sequenced individuals in southern Scandinavia from different genetic clusters (Fischer et al. 2024, Fig 2).

For this paper, the team of authors applied a suite of techniques - from biomolecular methods to traditional osteoarchaeology - to trace this individual's biography as far as possible. They considered his2 age, sex, and manner of death, his diet over the course of his life, general trends in his residential mobility, and the implication of his "foreign" genetics, all in the context of the local archaeological record.

What they came up with is the sort of incredibly textured and detailed narrative most of us can only dream of having the data to produce. Vittrup Man was born and spent much of his childhood somewhere in coastal northern Scandinavia where he ate a diet comprising wild, heavily maritime resources. During his early adolescence, he moved south and began eating a largely terrestrial diet consistent with an agricultural lifestyle. In adulthood (around age 30-40), he was struck in the head several times and put into a peat bog, which the authors very plausibly interpret as a sacrificial act and perhaps an honour to Vittrup Man.

A few things jumped out that caught my eye. First, the palaeoproteomic analysis of his dental calculus suggests that in adulthood he ate some maritime resources (including whale and seals) alongside a terrestrial agricultural diet. The authors note this is some of the first evidence for deep sea fishing and whaling during the Neolithic of the region, and that he may have played a role in this practice, based on his early experience among (likely highly adept) seafaring hunter-fisher-gatherers. There is also maybe some tension here among our categories - although Vittrup Man seems to have shifted into an agricultural world, he retained practices and foodways from his earlier life. Maritime products seem to have been shunned by some Neolithic European people, and in southern Scandinavia at this time may have formed part of a cultural border between Funnel Beaker (settled agriculturalists) and neighbouring Pitted Ware (hunter-fisher-gatherer) communities.3 So Vittrup Man's affiliations and sense of identity may have been complex.

Second, I was really pleased that the authors offered multiple possible narratives of his life. Archaeological data (even when it's as rich as in this instance) rarely tends to the sorts of singular, clear-cut narratives favoured by big science journals and press releases. Here, the authors suggest that Vittrup Man's move into an agricultural life style may have occurred because of his involvement in trade or because he was taken captive. These are both compelling possibilities, but they are not exclusive. We have abundant historic evidence that child captives could be taken to act as cultural intermediaries, translators and facilitators of trade and political engagement. Moreover, the act of captive-taking does not imply a life of servitude - in many places and times, captives were rapidly integrated into kin networks and welcomed into communities.4

The last thing that struck me (though it was only a minor point mentioned in passing) is that while people of mixed farmer/non-farmer genetic ancestry are found buried in Pitted Ware contexts, few are known from Funnel Beaker contexts. This reminded me of Graeber and Wengrow's5 discussion of the abundant examples of people (many women) who were kidnapped from or left colonial settlements and refused to return to European ways of life after experiencing other ways of living and relating. I'm not trying to draw a direct parallel - it just caught my eye.

All that said, my thanks to the Fischer et al for such a compelling, clearly written and complex case study!

-

Fischer, Anders, Karl-Göran Sjögren, Theis Zetner Trolle Jensen, Marie Louise Jørkov, Per Lysdahl, Tharsika Vimala, Alba Refoyo-Martínez, et al. 2024 “Vittrup Man–The Life-History of a Genetic Foreigner in Neolithic Denmark.” PLOS ONE 19, no. 2: e0297032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297032. ↩

-

Based on an assessment of the individual's sex as male and his find location, the authors dub him "Vittrup Man" and use he/him pronouns throughout. I'm not fully sold on this choice, but I'll use it for simplicity's sake here. I once again wish that English (or at least academic English) had a clear neutral pronoun set that implied nothing about a person's gender - they/them could have that affect, but it's clear that (in US English at least) singular they is now being taken colloquially as an indication of non-binary gender and this would also bias the text. Personally, as neopronouns go, I like e/em, but neutral and non-categorical seem particularly tough for my fellow anglophones. I live in hope. ↩

-

For a good overview see: Schulting, Rick J. 2018. “Dietary Shifts at the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition in Europe: An Overview of the Stable Isotope Data.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Diet, edited by Julia Lee-Thorp and M. Anne Katzenberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199694013.013.35. ↩

-

consider this some self-promotion: my co-authors and I discuss this at length in our forthcoming and open access book on migration to be published later this year. You can pre-order a copy now, or wait for it to be published and download it for free! Hofmann, Daniela, Catherine J. Frieman, Martin Furholt, Stefan Burmeister, and Niels N. Johannsen. In press. Negotiating Migrations. The Archaeology and Politics of Mobility. Debates in Archaeology. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ↩

-

Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. 2021 The Dawn of Everything. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ↩