Everyone you're looking at is also you

Mubi offered up Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. It begins with Baldwin walking along the Seine, smoking a cigarette, sporting a hat that looks rather like a nipple. It begins with a ‘co-operative’ Baldwin. The director doesn’t know what to do when Baldwin turns, decides he no longer wants to enact scenes from his life in Paris, no longer wants to talk about his writing. The work will far outlast himself, he says. The work will speak for itself.

There is a debate, on screen. The director challenges Baldwin, says he is unsympathetic to the creative team’s ‘system’ and ‘scheme’. Baldwin’s brow furrows and he says that he’s not unsympathetic – that he just doesn’t know how they could do it. And then a disarming smile, as if to say “How can you understand me, portray me, with this scheme that applies to all men?”

Baldwin pushes. Insists they conduct an interview in front of the Bastille monument. Insists on an audience in his painter friend’s studio. Insists that his own companion speaking out is an act inherently more mortally risky than is the creative team’s endeavour. And it isn’t until the director concedes what he doesn’t know, confesses that through Baldwin’s books he is coming to an understanding, that there’s a softening. Now, we can begin, says Baldwin.

===

Toward the end of the Meeting the Man, the director suggests that Baldwin’s stories are more powerful than his essays, because they hone in on universal experience. ‘Everyone knows what it’s like to fall in love,’ the director says, but Baldwin will not concede that, not on evidence. What he does say about everyone is this: Everyone you’re looking at is also you. Maybe this is the difference between these two men: Terrence Dixon, the director, assumes what is universal about much of human experience; James Baldwin, the citizen, knows that what is universal is that we see people through the lens of our own experiences. It’s no surprise, then, that my recent exposure to Tarot surfaced in this viewing.

It feels to me like Baldwin is acting as page, or at least that his own page is acting, in Meeting the Man. Baldwin starts out, but when he comes into a lived understanding of the dynamic of the creative team, he pauses. In identifying what is going on, taking a moment to ask himself and the team is this what you want?, he makes the rules of engagement explicit. This enables the only complicity that is worth anything: the conscious.

How often do we enter into something simply trusting our instinct? Enact complicity on some form of intuition? When, truly, are we explicit and direct? Living in this way sounds both exhausting and a way of occluding the mystery and poetry of experience. But witnessing it, there is also a sense of relief. A breath of welcome air gusting into these prisons of assumption that we build for ourselves. We need not live this way, entirely; but about some things, we cannot live at all without making the pacts between us known and consensual.

There was Baldwin in his Queen of Swords, upholding his boundaries, making himself unassailable; here he is again as King of Swords, speaking his truth, no matter how the ground make shake. Only by protecting himself – as citizen, as one of the prominent Black voices of 1970 – could he attempt to engage. Only by speaking the truth as he sees it – being sick of the ‘salvation’ foisted upon him, wanting his work to speak for itself – could he enter into the creative dialogue.

When his strength and truth are acknowledged, Baldwin softens. He becomes a lover again, not a fighter. Now we can begin. I’m with him in thinking that not everyone knows what it’s like to be in love. Moreover, I witness much that is proclaimed as love treading only in the light and denouncing the shadow. To invoke the spirit of bell hooks, love in the doing necessarily walks a line between the fierce and the tender. You cannot love unless you are prepared to challenge; you cannot rescue unless you will concede the ultimate autonomy of another’s being; you cannot live alongside another unless you allow the space necessary for vulnerable things to flower; you cannot befriend unless you can see pain; you cannot call on another unless you accept that they may turn away; you cannot appreciate another unless you acknowledge that people will change; you cannot advise unless you know others also have solutions; you cannot create until you’ve got your hands wrist deep in the rich compost in which you hope to sow seeds. Terrence Dixon needed to know that. We all need to know that.

===

After the film ended, Kenzie asked if there was any of Baldwin’s work in the Apiary, mark II. We found the only work of his to apparently go out of print, Jimmy’s Blues (a collection of poetry); as well as old copies of A Rap on Race; Nobody Knows My Name; and Giovanni’s Room. It was the latter we settled on.

Kenzie made a nest of blankets in front of the wood burner, lying on her back in front of the fire, at that humming ember stage. She turned out the overhead light, lit a few candles. I sat in a low chair in the glow of the anglepoise lamp, bookcases to my right. And I read that potent first chapter aloud, dampening the sharpness my accent can sometimes hold so as to better match the mood of the room and the tone of the words. My gaze flicked often to the reposing sweetheart on the hearth.

When Kenzie suggested we swap positions, my assent was swift and easy – having seen her there, I could see myself nestled, too. Kenzie read a poem to me called Confession. James Baldwin knows how to play just as well as he knows how to pluck at those heartstrings. The fierceness and the tenderness – Baldwin brings both to unflinching life.

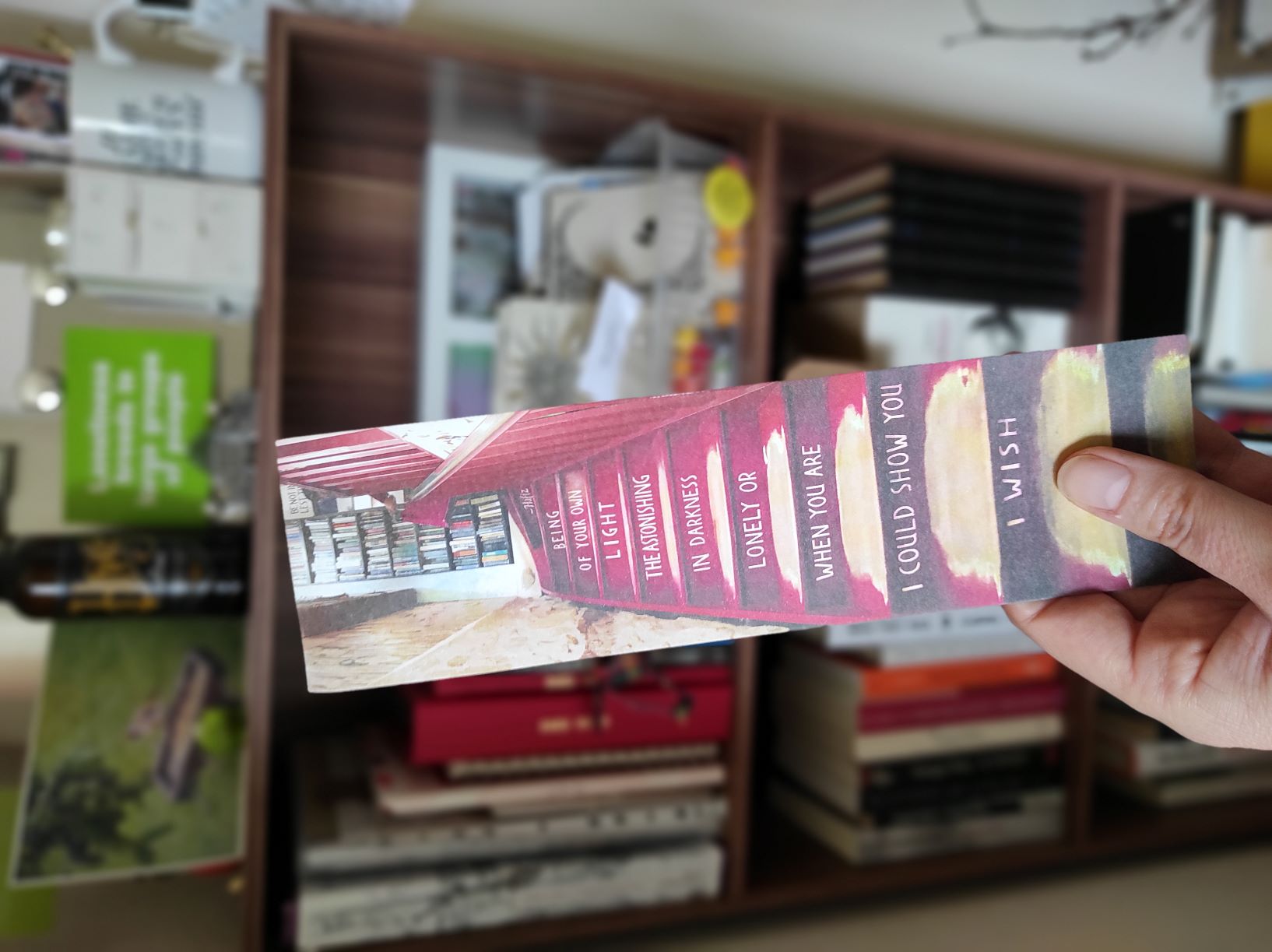

Artists, Baldwin said in a Paris Review interview, help us see reality again. Susan Sontag remarks we are what we are able to see (hear, taste, smell, feel) even more powerfully and profoundly than we are what furniture of ideas we have stocked in our heads. I don’t profess to know what Baldwin means when he says that everyone you are looking at is also you, but I think about what we do see, about how much recognising characteristics in others helps us to see them in ourselves too. I wish that for all of you – to witness, sure, your own foibles and foolishness, so that you can overcome; but moreover, to see the incredible light of your being* reflected on the retina of those who have the pleasure of encountering you.

When I see Baldwin, boldly protecting the bounds of his experience and telling his truth from the mountaintop, I feel that in me – yes, I have not lived in his prison, but I feel the walls of my own. And when I notice that I look on others with kindness and love, I understand that the same gaze can be turned inward, to myself.

*Props to Allison and Shakespeare and Co.