Expedition 9

The Bathysphere

Welcome to the ninth expedition of the Bathysphere! This week we have skiing, towers, art and archival unboxings for your perusal. Keith’s essay is on the body’s internal signal system and how it has (or indeed hasn’t) been simulated in video games. Oh and have you heard of the Cromemco TV Dazzler? Check out the retro section at the very end of this transmission…

As ever, part of the newsletter is free, part is only available to paid subscribers. Please consider signing up for an annual subscription which will allow us to stay aboard the Bathysphere for longer. Thank you – and enjoy the journey!

The Bathysphere crew

Christian Donlan

Florence Smith Nicholls

Keith Stuart

Contact us at bathyspherecrew@gmail.com

Delightful games

I tend to fall in and out of love with the tower defence genre, erring more toward the latter than the former territory. However, Rift Riff, the latest project from Hidden Folks designer Adriaan de Jongh, is a joyous take on the familiar archetype with a beautiful sense of style and many cute touches, including a sort of town-planning mechanic that let’s you cue up new towers before you have the resources to build them. Rift Riff is six quid on Steam: a steal. KS

I think it was Lauren Laverne who said that, when it comes to words, “skiing” is right up there. The rare double I! Who isn’t on board for that?

This week I’ve been enjoying the word all the more while playing - maybe replaying - Skiing Yeti Mountain. It’s getting on a bit, but it’s still an iOS go-to. Lovely skiing controls, a thudding sense of connection when you hit a tree, and a little more mystery to the story than you might be expecting. Have I seen the yeti so far? I have not. But I keep hoping. CD

Interesting things

Mirror’s Edge Catalyst is one of those games that sort of passed me by when it first came out. It has a lovely sense of pace and speed, and a lovely approach to the texture of an open-world, but I’ve tended to play it in little chunks and then immediately forget about it.

That’s until last week when I suddenly discovered I had reached Mirror’s Edge TikTok. Video after video of this beautiful, liminal world scrolling past. I tend to think of this as a bleached white game, but it’s actually anything but, those rooftops and passageways taking on the stain of an ever-changing skybox. And I tend to think of it as clinical and chill, when, to see it like this, it’s actually dreamy, improbable, and filled with quiet wonder. CD

Because I can’t help myself, I’m once again suggesting an academic book this week, though to be fair it is related to Keith’s essay. This one is Brendan Keogh’s A Play of Bodies How We Perceive Videogames. It's described as “an entanglement of eyes-on-screens, ears-at-speakers, and muscles-against-interfaces.” If you’re interested in what it means to play a video game beyond just what’s on a screen, I’ve got a feeling you’ll like this one. FSN

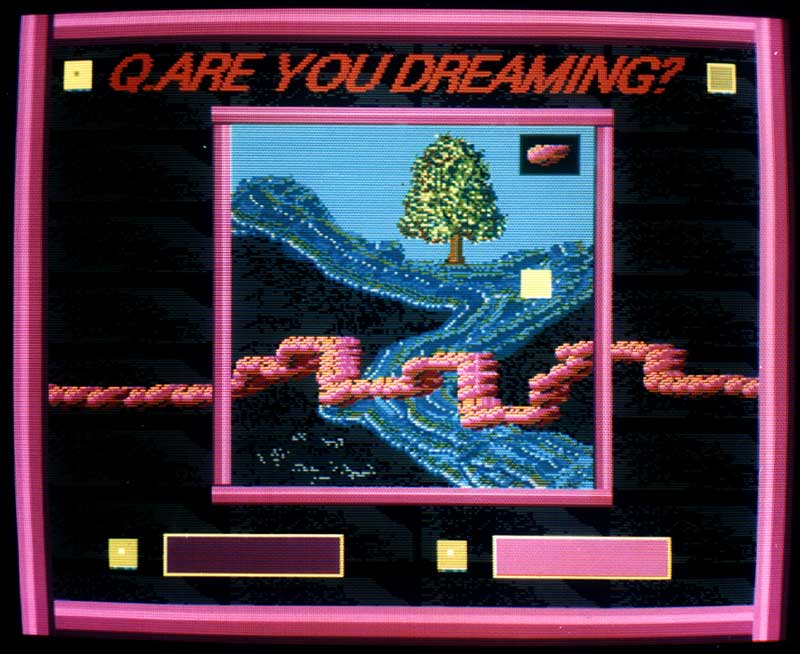

Electric Dreams Art and Technology Before the Internet is on at the Tate Modern until June 1st. It’s got some interesting examples of optical and kinetic art, but I’d say it's worth going just to see Suzanne Treister’s Fictional Videogame Stills from the early ‘90s. Inspired by visits to arcades in London, she created these in Deluxe Paint II on an Amiga. The original floppy disks have been corrupted, now only photographs she took of her Amiga screen remain. FSN

Recently, the Video Game History Foundation was gifted 50 boxes of old video game mags and on Wednesday, the team ran a livestream of the grand opening. There are some familiar titles in there – including lots of copies of Game Informer and Nintendo Power – but also a few delicious rarities including the early 1980s console mag Arcade (not to be confused with Future Publishing’s late ‘90s gaming lifestyle mag of the same name) and the wonderfully titled, Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. Although it made me seethe with envy, it’s worth a watch for the excited reactions! KS

Essay: nothing on the inside – games and interoception

I’m afraid this essay is going to start in the most middle-class way possible – with something I just learned about on Radio 4. Interoception is the ability to sense and interpret the signals sent from your bodily organs to your brain. On a basic level, that means knowing when your bladder is full or that you need to eat something, but the signals can be more subtle, such as a rise in heart beat or a slight clenching of the muscles in response to a potential threat, and not everyone reads them well. According to the report I listened to on the Today programme, neuroscientists are becoming increasingly excited about the extent to which interoception informs our experience of the world. Research suggests that sensitivity to these internal signals can determine our capacity to regulate our emotions, with ramifications for our mental health. Importantly, these physiological indicators happen before we’ve had chance to process the emotional meaning. You know when you walk into a pub or restaurant or social gathering and you just feel there’s something off but you can’t place it? That’s interoception in action.