Expedition 6

The Bathysphere

Hello and welcome to the sixth expedition of the Bathysphere. Today, we’re introducing paid subscriptions, which will allow us to continue this endeavour. That’s if they work – we’re not quite sure we’ve mastered the system. We’re offering a monthly subscription for £3 or an annual sub for £25. A portion of each newsletter will always be free. Subscription details should be provided somewhere on this newsletter. Thank you for joining us.

The Bathysphere crew

Christian Donlan

Florence Smith Nicholls

Keith Stuart

Contact us

Delightful games

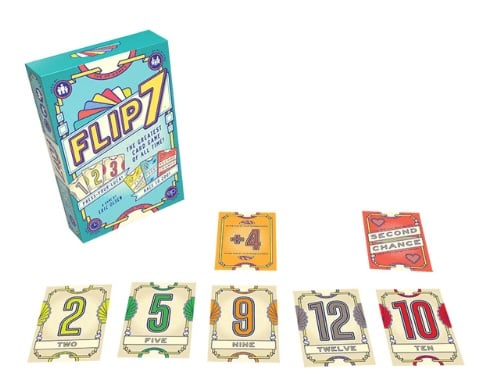

Flip7 is a card game created by Eric Olsen. It’s a push-your-luck game, and it’s incredibly simple to learn and teach and play. The cards have numbers from one to twelve on them, and players are dealt a single card at a time. Each turn they have to decide whether they want another card or whether they want to bank the numbers they have so far. If you manage to reach seven cards, the round’s over and you get a bonus. If you get a double of one of the cards you already have, you lose your cards and you’re out for this round. First player to 200 points wins, and the wrinkle is, the higher the number on the card, the more copies of that card there are in the deck. Magic. CD

I was a big fan of the experimental boom period of computer role-playing games – let’s call it the mid-80s to the late 1990s – when the form and function was still being decided. It’s lovely then to see a cult star of the era, Gates of Skeldal (aka Brány Skeldalu) getting a re-release on Steam. This 1998 gem from Czech developer Napoleon Games is filled with interesting ideas and puzzles, and it’s yours to discover for less than a fiver. KS

Oh, you should also check out Many Nights a Whisper, an experimental narrative archery game about carrying the weight of a society’s expectations on your shoulders while trying to hit a distant target. It’s the latest title from deconstructeam and you can but it for £2.50 on Steam. KS

The Internet Archive recently ran a game jam that required all entrants to make games that were at least 50% composed of assets from their “search engine for vintage data” DiscMaster. There’s a whole plethora of free games on the theme of media preservation. DiscMaster mostly contains pre-web or early web assets, and the interactive experiences inspired by that assemblage of oddities is something to behold. (Also, full disclosure, I have an entry in the jam). FSN

Interesting things

When I first left university I was a Kelly girl for a few years. I know the company had rebranded by that point, but we were still called Kelly girls - my mum, who had been a Kelly girl back in the day thought it was wonderful. I loved temping - getting to see inside all these weird buildings in Brighton, meeting people for a few days and hearing their stories and what they planned to do for lunch and then disappearing. Sometimes I see a face on the bus that I know but don’t know and I realise I met them when I was a Kelly girl.

Anyway, I’m reading Temporary by Hilary Leichter at the moment, and it’s a novel all about the temping life. It’s surreal and sometimes mundane and funny and surprisingly moving and I think it’s wonderful. It’s one of those magical books that feels both utterly coherent and as if it had been spun out of the air itself, as if Leichter sat down to write each morning with no idea where she’d be in the next half hour.

It’s a book that changes completely every thirty pages, which means it’s a pretty harmonious fit for temping. It’s magical realism, I guess? (I never quite know what’s magical realism and what isn’t.) But for all that, it feels very similar to my days as a Kelly girl, even if I never got a gig on a pirate ship.

(One last thing. One of the best things about being a Kelly girl was the lunches they provided every Friday in the office. You’d wander over with your new Kelly girl friends and for half an hour eat like a rich person. M&S curry and all that jazz. It was a good life.) CD

The annual Game Developers Conference has started adding talks from the 2025 event into its online GDC Vault and it’s really worth perusing the free section. My recommendation is Teabag in First: How 'Thank Goodness You're Here!' Does Comedy a hugely entertaining and suitably shambolic guide to last year’s fantastic comedy game. KS

On the topic of games academia, this week I’ve been at the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Yokohama, Japan. Many of the papers from the conference are open access. Just one examples is “This Game SUX: Why & How to Design Sh@*!y User Experiences” by Michelle V Cormier et al. FSN