Expedition 40

The Bathysphere

Happy 40th expedition! As you heard from our emergency communication, we’re changing things up at The Bathysphere. From now on, the entire newsletter will be free to read, including the main essay. While Keith will pop back on board now and again, for now Chris and Florence will take charge of steering the submersible. Thank you for voyaging with us!

The Bathysphere crew

Christian Donlan

Florence Smith Nicholls

Keith Stuart

Contact us at bathyspherecrew@gmail.com

Delightful games

Want to find a new way to get more steps in? Perhaps you should play the surreal game Staircore, which is about, among other things…stairs. FSN

Interesting things

Inspired by Chris’ piece on Glass Town and paracosms, I’d like to recommend Gianni Rodari’s The Grammar of Fantasy. Rodari is one of Italy’s most influential writers of children’s literature in the 20th century. In his own words, The Grammar of Fantasy “discusses some ways of inventing stories for children and how to help children invent their own.” FSN

If you’re looking for an early Valentine’s activity, then I can recommend Alistair Aitcheson’s interactive clown show in which he plays a maid called Mademoiselle Cafetière on a date with none other than the dashing actor Pierce Brosnan. The twist is that the audience gets to control what Brosnan (actually a dummy) says through a bespoke mobile app. If that sounds like your delightfully strange cup of tea, come to Theatre Deli in London on February 6th! FSN

Essay: Glass Town

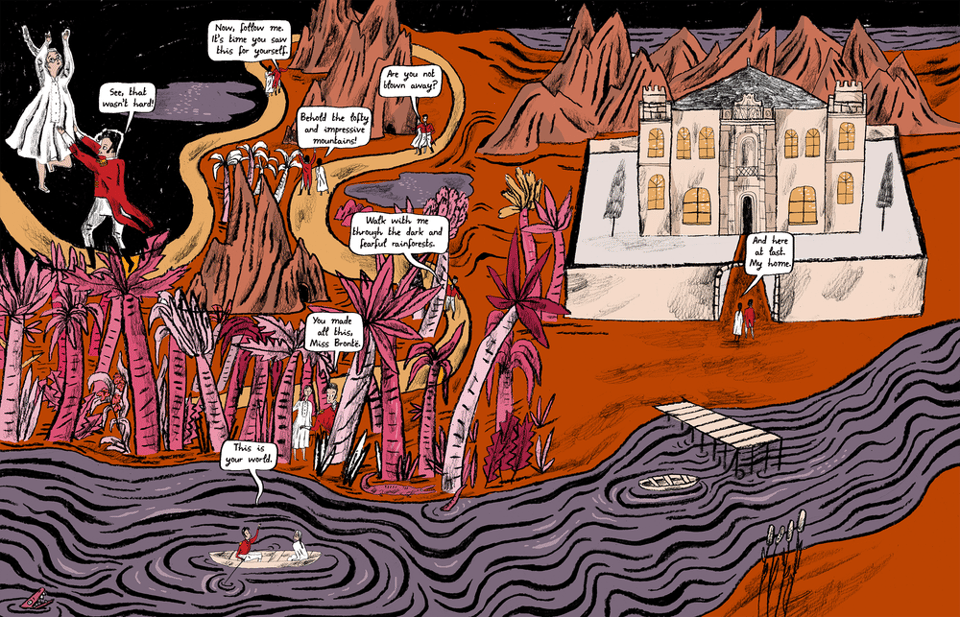

I read Wuthering Heights over Christmas, and I’m still recovering it. By this weekend, though, I had clearly recovered enough to read Glass Town, a graphic novel by Isabel Greenberg, which is related to Wuthering Heights in intriguing, and distinctly game-like, ways.

Glass Town is the lightly fictionalised story of four of the Brontë siblings, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne. It in turn revolves around a fictional world the four created together, and then expanded upon in various stories and poems. The whole thing began in the 1820s, I think, when Branwell was given a box of twelve soldiers, which he shared with his siblings. Eventually they would build a complex political world loosely based on West Africa. A series of different islands formed the Glass Town Confederacy, and by the early 1830s, Branwell and Charlotte were left in charge of the country of Angria, while Emily and Anne created a new country - I think it’s a country - called Gondal.

Greenberg’s graphic novel is really wonderful, and for the Brontë fan it contains lots of fascinating little connections between the imaginary worlds that the children played in and the novels that the adult Brontës would go on to write. Much of the Angria and Gondal writing ended up being published as juvenilia, and I’ll track it down at some point. For now, I am happy to report that Gondal has its own entry in Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi’s glorious reference book The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. (It’s slotted in between the village of Goldenthal and Gondor from Middle-earth.)

I gather lots of writers have taken inspiration from Gondal and Angria over the years, including Keiron Gillen and Stephanie Hans in the comic series DIE. More than anything, though, I’ve been struck by a term used to describe Gondal, Angria and creative works like it: paracosm.

A paracosm is a detailed imaginary world that generally originates in childhood. If you’re like me, the discovery that there’s a term for this kind of thing will lead to a kind of “of course” moment. My sister, who was a very creative child, once had a very complex paracosm in which family members had various roles and even the junk mail that arrived at the house has a special meaning. We were also big fans of the book Harriet the Spy as kids, and I think Town, the game that Harriet plays - it has been an age since I have read this, so I may be wrong - counts as a paracosm too.

Paracosms, I think, are interesting things, and I would love a dictionary of them that might overlap with Manguel and Guadalupi’s book in interesting ways. I love the fact that they’re works of sustained and diffuse fiction, but they emerge in a play-like way, with ideas offered up and consensually fitted into a growing whole. It reminds of D&D campaigns, but it also reminds me, personally, of a period in my life after I left university and I spent a year working in health insurance during the day while writing a truly unforgivably shit novel in the evening.

The novel was complex and tedious and I found it recently on an old drive and it’s a properly cursed object, but the process of writing it was distinctly paracosm-like. Every evening after a day of data entry, I went into this brainless imaginary world I was putting together and just created a bit more of it each time. Maybe this kind of process also lead, more happily, to Wuthering Heights.

I’ve always suspect the business of crafting fiction is akin to play. Friend of the Bathysphere Simon Parkin was just telling me the other day about Nabokov standing his characters up before writing each day and telling them to behave, and isn’t there something of the elaborate imaginary world in Pale Fire? Play, imagination and fiction: these things are hard to stir apart, I think. And any attempt to do so will probably leave you with The Dictionary of Imaginary Places and Wuthering Heights on your desk, so that can’t be a bad thing. CD

Add a comment: