Expedition 2

The Bathysphere

Hello and welcome aboard for our second dive! We’re absolutely delighted that so many people have joined us. Please do get in contact and let us know what you think. We’re especially keen to hear about forthcoming events that may be of interest to video game players and thinkers. These could be film festivals, architectural talks, occult lectures, anything that nudges on the structures, cultures and narratives of games. For now, please enjoy your time with us as we descend together.

The bathysphere crew

Christian Donlan

Florence Smith Nicholls

Keith Stuart

Essay: Submerged play by Florence Smith Nicholls

Back in the halcyon days of 2008, Nick Taylor wrote an article on the state of ethnographic research in MMOs. Ethnography is a research method originating from anthropology, broadly referring to studying a group or culture in their natural environment. During the golden age of MMOs, there was also a golden age of MMO ethnography, with academics chronicling the communities in games such as Everquest and World of Warcraft. Nick lamented how this work tended to ignore the lived experience of participants beyond their avatars on the screen, and that the academics involved would erase their own presence in the research. He labelled this trend “periscopic play.”

Periscopic play implies looking from a distance. Being apart, aloof. Further than this, Nick was worried that anthropologists were emulating the old colonial narrative of the lone ethnographer who enters the ‘pristine wilderness’ of the video game, set apart from other players by their apparent expertise. This is something I tried to avoid in my own peri-ethnographic work in the MMO Wurm Online, a fantasy sandbox game with a particular focus on crafting.

Wurm has been around since 2006 and has a small but dedicated player base. I’m a PhD researcher in video game archaeology, and I was interested in players’ relationship with the game’s community heritage. To this end, I adapted an existing research technique known as the “go-along,” where you literally go on an everyday walk with a participant, to digital space - meeting participants in-game and walking with them through the semi-abandoned landscape of Wurm. Any possible misconceptions I could have had about my own expertise were quickly dissipated when, during a go-along with the curator of an in-game museum, I got stuck trying to climb a ladder.

In the subsequent research paper I wrote about the go-along, I tentatively put forward the idea of “submerged play” in contrast to Nick’s “periscopic play.” Not to say that my Wurm escapades are the answer to decades of video game ethnography, but to pose the question: what does it mean to put our own messy, embodied experiences into the stories we tell about play? Who, and what, tends to get included in the frame of the periscope?

It’s not that there isn’t interest in chronicling the physical context of gaming - we only have to look to streaming culture for the answer to that. Take a recent stream by Tom Walker, in which he dressed up as British sitcom character Mr Bean and played the driving simulator BeamNG.drive. He even made a bespoke alt controller, a steering wheel that he operated by pulling a string like in the classic episode “Do-It-Yourself Mr. Bean.” The physical comedy, the performance, is the whole point. Yet, even as these kinds of streams are charming precisely because they involve improvisation, they are still curated experiences for an audience. This is true for social media posts about gaming, like a tasteful shot of playing a Switch on the beach posted to Instagram. These also provide context for how people enjoy video games, but again, much is left out of the frame.

The physicality of gaming is often a point of interest when talking about skill or achievement. An interesting example of this are the countless YouTube videos out there on the adoption of a technique known as “rolling,” in order to set new world records in Tetris. This involves positioning your thumb over a D-pad and then rolling your fingers on the bottom of the controller to push it up into your thumb so you can tap the button faster. Of course, these details are of interest because they involve ingenuity and community knowledge-sharing, even if they don’t pertain to everyday experiences of gaming.

Perhaps an anathema to the focus on skill; the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision conducted a project in which they invited visitors to be recorded playing on an original Commodore 64 with a small selection of Dutch games from the mid-80s to choose from. The result was an insight into how contemporary players struggle with a different generation of design conventions, and intergenerational conversations between parents and children about these experiences.

Thinking about the physical context of video game experience, one of the most useful concepts I’ve come across is the “assemblage of play.” This was put forward in a 2009 article by another video game ethnographer, T. L. Taylor, and refers to the need to consider play in terms of the full assemblage of player, hardware and software, not just what happens on screen.

Did I want to write about “submerged play” just because it also coincidentally had deepsea aquatic connotations that chimed with the name “Bathysphere”? Did I want the opportunity to make a cheap pun about “deep dives” on gameplay? Perhaps. But it’s also true that the question of what it means to be a physical body that engages with a digital world for both the study and preservation of video gameplay keeps me up at night. The “go-along” in Wurm Online allowed me to reflect on my own frustrations with conducting an interview in a game where I didn’t understand the keymapping on a Steam Deck, and the uncanny experience of having deep conversations with a someone I’d never met in person about how their artistic practise irl overlaps with their in-game curatorial role. Yet, I couldn’t see the context in which they lived day to day.

When it comes to understanding the context of play, a bricolage of approaches may be best, each giving different insight and having differing relevance according to the affordances of an individual game. In short: there’s such a deep well of experience out there, and my account of submerged play is but a drop in the ocean.

Delightful games

I was introduced to Lushfoil Photography Sim by the editorial team at EDGE back when I wrote a piece on photography games for the mag a while back. I hope they don't mind me returning to it here. Anyway, I just checked and the demo is still available. Lushfoil is perhaps the purest photography game I have ever played. It's you and a camera and a range of environments to pick through and sift for good angles. What I love about it is that it teaches you the rudiments of photography in the best way - by encouraging you to take lots and lots of photos, experiment with the settings, and just see what seems to sing on the page. From there, you can start to work out why it sings and what might make it sing even louder. And at that point, I'm afraid, you will be a photographer, which means you'll have a dozen eBay tabs open as you track down that Japanese TLR you absolutely have to own. Sorry about that. CD

I’m just going to go ahead and recommend that you play Atomfall, Rebellion’s post-apocalyptic adventure set in Cumbria. I enjoy the fact that it feels like a PS3 game, not because it’s technically retro, but because its structure goes against the rules of contemporary open-world design. It also feels very British in its language and humour, and that’s rare for big budget games now. It used to be that the UK had publishers such as Eidos, Gremlin and Ocean making ambitious and culturally idiosyncratic adventures, but those companies are long gone. Atomfall feels like an artefact from another era – flawed and a little broken, but extremely resonant. KS

Interesting things

While I was in San Francisco for GDC, video game historian Laine Nooney recommended the Musée Mécanique to me, so now I will recommend it to you. It is a collection of more than 300 antique slot machines and other coin-operated ephemera dating from the turn of the century to modern day. My personal highlight was a lamp that you could pay 25 cents to turn on. FSN

Now a modern classic, Carly A. Kocurek’s Coin-Operated Americans: Rebooting Boyhood at the Video Game Arcade was written just before Gamergate and remains essential reading for anyone interested in the history of video games. It focuses on the industry between 1972 and 1985 and draws from a range of archive sources to show how the “technomasculine” culture of gaming was constructed. FSN

In a similar vein to the above, Gaming and Extremism is a timely and fascinating collection of essays about video games and radicalisation edited by Linda Schlegel and Rachel Kowert. It’s published by Routledge and a free digital version has been made available via a creative commons license. Physical copies can be purchased via the Routledge site. KS

I put off reading Dead Souls, by Nikolai Gogol, for at least two decades because I assumed I would be too thick to enjoy it. Luckily, I got over myself and read it a few months back, and I've been thinking about it ever since. I'm sure a lot of the book's elements did soar pleasantly over my head, but what I was left with is a truly singular black comedy: Chichikov, a mysterious stranger who's unduly fond of his own perfectly round chin, turns up in a rural community in Russia and wants to buy the serfs, or souls, owned by the nearby gentry. Not all the souls, though - just the souls of those who have died.

What follows is an astonishing book whichever way you cut it. Chichikov is a conman at heart, but the thrust of his con is that he's essentially come across a new way of thinking about money. So the book unfolds in a series of encounters between him and various rich idiots, some of whom are canny rich idiots, as he tries to get them to think about money and property and human life in a new way so that he can achieve his gloriously idiotic aim.

Dead Souls was written in the 1840s, I think, but it belongs to that magical group of books which remain funny and exciting decades after conception - Cold Comfort Farm is another, incidentally, a parody of a literary genre that doesn't really exist anymore and yet it's still brilliant. But what's most striking about Dead Souls is how relevant it feels to read it in the age of Crypto Bros and NFTs and all that jazz. Chichikov would be very at home in Silicon Valley fleecing various billionaire bumpkins. CD

In case you missed this ‘going viral’ recently, OSEBA is an elevator button museum in Hachioji, Japan, created by the Shimada Electric Manufacturing Co. It’s hard to get in apparently, but if you do, you can push historic and futuristic elevator buttons, all of which are displayed on vast interactive walls. Obviously, there are also elevator button-pressing games, too. KS

Retrospective adventures

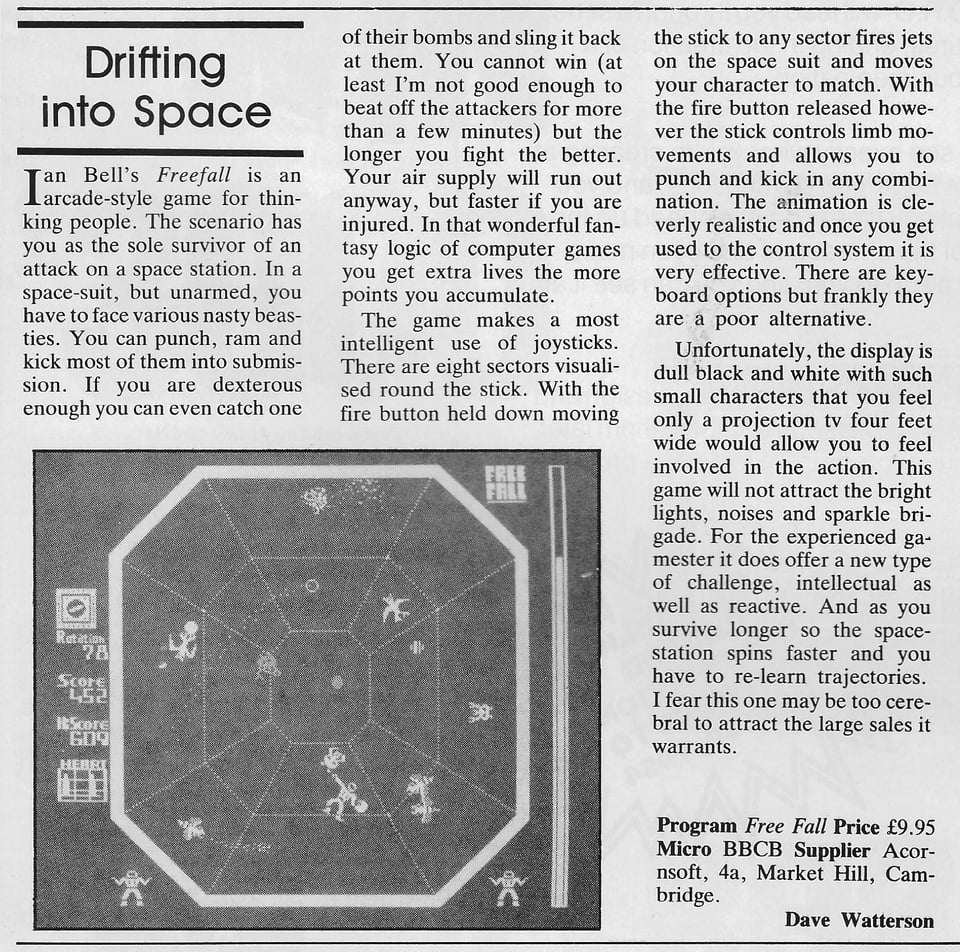

One of my favourite things about trawling old games magazines is finding reviews for games you’d never heard of, mostly because they were not considered worthy of “the canon”. This one is from the May 24-30 1984 issue of Popular Computing Weekly – it’s a look at a curious space shooter/brawler by Ian Bell who would go on to co-create Elite. Players direct an astronaut around the eight sectors of a space station blasting, punching and kicking aliens. It has a strange control interface, almost like a precursor to dual-stick shooters. Ian refers to it on his home page as “the first ever beat-em-up”. It’s definitely not that, but it IS an intriguing relic of the BBC Micro era. KS

End of expedition 2

Thank you for reading! You can contact the crew at bathyspherecrew@gmail.com and we welcome amiable feedback. It gets lonely down here.

Add a comment: