Wednesday, May 31, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_______________________________

3 articles. Reflections on the week. So far.

Articles are long but worth your time.

Today, the 102nd anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre.

How One Family Told the Story of the Tulsa Massacre.

Part of Greenwood District burned in Race Riots, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, June 1921.

Part of Greenwood District burned in Race Riots, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, June 1921.

They called it the Eden of the West. When boosters crafted tales of the land known as the Creek Nation, Indian Territory, and eventually Oklahoma, they wrote of fertile soil that could grow any crop, yielding shoulder-high acres of wheat and melons ready to burst in their succulent ripeness. They described a righteous realm where any newcomer would have “equal chances with the white man,” while those who remained in the old world, the Deep South, were “slaves liable to be killed at any time. Most important to J.H. and Carlie Goodwin, they spoke of good schools for colored children, places where the seeds of prosperity could be sown in the one terrain that could not be burned, stolen, or erased by an interloper—the terrain of the mind.

James and Carlie did not decide to move to Oklahoma spontaneously, for spontaneity was not a luxury that Black people could afford. James was a quiet, deliberate man who sought success with a patient vigor. In the early 1910s, he and his wife lived on a segregated street in a small town in Mississippi called Water Valley, along with their four children: Lucille, James Jr., Anna, and the baby, Edward. They knew their offspring deserved better than what little had been possible for them in the hardscrabble aftermath of Reconstruction. In Water Valley, Black children were offered no schooling beyond the eighth grade, and a Black man was expected to scurry into the gutter when he encountered a white man on the sidewalk. “He did not want to be in a place where the safety of a Black man could be so lightly treated,” J.H.’s grandson Jim explained decades later. “He didn’t want his kids exposed to that.”

Oklahoma offered something different. Here was a place where three-quarters of Black farmers owned their acreage and more than 80 percent of Black people could read—a higher literacy rate than any state in the South. Between 1900 and 1920, Oklahoma’s Black population tripled as people trekked to the state however they could, on crowded trains or weary covered wagons. A few even came on foot. Keep coming, implored one former Mississippi journalist who had made the journey. “Now is the time for the progressive negro to come west to seek a home. . . . It is superior to any other section of the United States.”

In the fall of 1913, J.H. ventured to Tulsa on a scouting mission. He knew that the place was known as Magic City, the Many Millionaire City, even the Oil Capital of the World, but he needed to see for himself whether this was a suitable town for a Black man to open a business and provide a quality education for his children.

Standing on the train platform of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad, J.H. could gaze up and see the epicenter of the city’s wealth just three blocks south. The Hotel Tulsa, twelve stories tall and half a block wide, was the largest new downtown skyscraper, the place where oil barons brokered all their million-dollar leases. Lounging in the decadent hotel lobby, these men pored over table-size maps that lent cold authority to their contractual conquests. If this city was indeed magic, those men believed they had the monopoly on it.

But J.H. turned his back to the hotel and walked north, across the Frisco railroad tracks, toward a small but growing Black neighborhood called Greenwood. That was where he would have to build his future.

When J.H. first stepped onto Greenwood Avenue, it wasn’t much to look at. The street was unpaved, with uneven sidewalks that were set below the street in places. On a dry, sunny day, the road might be clouded by a haze of dirt; on a rainy one, it became a muddy impasse so waterlogged that one observer called it “a splendid opportunity for some mariner to put in a ferry.” Underground, there were no pipes to provide most residents with clean water in their homes; up above, there were no streetlights to offer comfort and safety outside them.

But J.H. recognized that a spirit was germinating on this street that went beyond its humble appearance. He saw a two-story brick building anchored by The People’s Grocery Store, which had been the very first business opened on the block back in 1905 by O.W. and Emma Gurley.

Just steps away from the People’s Grocery was the three-story Williams Building, where Loula Williams sold fruits and fountain drinks in her popular confectionery. A few doors north, brothers Jim and William Cherry owned a pool hall, where men went to drink, shoot dice, and tell lies. A new croquet garden on Archer Street offered “first class” recreation, while homegrown chefs sold plates of chitterlings and pigs’ feet out of make-do restaurants down the block.

The owner of the Crystal Café blared his wailing electric piano around the clock—even on Sundays—as the violin teacher at the Tulsa Colored School of Music pleaded with his neighbors to “learn real music and not be carried away in that idle ragtime.” On side streets, women did hair in their kitchens and men bankrolled gambling dens outside the eyes of the law. All of it was run by a population of roughly five thousand Black people, a community of kin on a scale J.H. never witnessed in tiny Water Valley.

The sidewalks were not filled with white men who demanded Black people simper in their presence; they were filled with Black men, women, and children, shuffling in and out of all those storefronts, all the time, walking tall and proud.

J.H. liked what he saw. He decided to buy a house on a hill on Elgin Avenue, only a short walk from the bustle of the business district. He sent a telegram home to Water Valley instructing his wife to pack their things because he had found the family a new home. Carlie and the four children soon piled into a train in Water Valley on their own sojourn to Tulsa. Carlie brought blankets for him to snuggle under during the long ride, along with fried chicken and ham sandwiches tucked into old shoeboxes. As their train approached its final destination, the porter, a towering Black man, bellowed out each locale. For the Goodwins’ youngest child, Edward, his world grew with every stop.

“Jonesboro, Arkansas! Jonesboro, Arkansas!”

“Monett! Monett! Monett!”

“Afton! Afton! Afton, Oklahoma!”

And finally: “Tulsey, Tulsey, Tulsey Town! Tulsey Town, the TushHog town!”

When the family arrived J.H. was waiting for them just off the train platform with a horsedrawn cab and a heart full of ambition. But moving to Greenwood, of course, was much more than just a business venture for him and Carlie. The Goodwins had sold off all their property and trekked to an unknown land for the sake of their children. Edward, the baby of the family at eleven years old, would get to spend the most time in Tulsa’s superior schools. He, more than any other Goodwin, would know what it was to live in a place where every Black person seemed to be striving for something greater. It would spark a drive in him that was never extinguished. “There was this outstanding and remarkable showing of energy,” he reflected, decades later, on those early years of Greenwood. “They were creating their own way of life for themselves.”

Young Ed, who had moved to Greenwood as a child with such wide-eyed wonder, was a high school senior on May 31, 1921. He was rehearing for a school play and dreaming about attending college at Fisk University when a small boy burst into the performance and exclaimed, “They are trying to lynch a colored man downtown!”

“From that moment, Ed’s entire world changed. Over the next 24 hours, a white mob descended upon the neighborhood, destroying Ed’s home, his church, and his universe. Overall, during the events that would later be known as the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1,256 homes were burned, hundreds of businesses were destroyed, and up to 300 people were killed. “I have never again seen some of the people I had known,” Ed reflected decades later. He always assumed many of them were murdered.

Ed Goodwin (top middle) with his high school classmates in early 1921. Ed was days away from graduating when a white mob burned Greenwood to the ground.

Ed Goodwin (top middle) with his high school classmates in early 1921. Ed was days away from graduating when a white mob burned Greenwood to the ground.

But Ed and his family didn’t leave Greenwood—they rebuilt. Ed’s father J.H. became a leader of a relief committee that helped provide supplies and legal aid to newly destitute residents, while his mother Carlie soon filed for a building permit on the same spot where their grocery store had been burned to the ground. Greenwood rose, phoenix-like, from the ashes, and the Goodwin clan grew alongside the revived community.

Ed went off to Fisk and returned home with his genteel college sweetheart Jeanne, a clever and caring woman from Illinois. The two soon started a family. Greenwood, meanwhile, transformed back into what Ed called “a mecca for the Negro businessman—a showplace.” The neighborhood was a place where nightlife thrived, small businesses flourished, and an underworld economy lived comfortably alongside public storefronts. Ed dabbled on both sides of the law, opening a haberdashery and shoe shine parlor while also operating a numbers racket that generated hundreds of dollars a day in revenue.

After making a small fortune running his gambling enterprise during the Great Depression, Ed decided to enter the news business. He was guided more by self-interest than altruism—he wanted to clean up his name after the white press dragged it through the mud by christening him the so-called “Policy King” in Tulsa. “I had a selfish motive,” he admitted years later. But while relentlessly looking out for himself as a young man, he had constantly butted up against the edges of what Black progress allowed for in the age of Jim Crow. Post-massacre Greenwood was plagued by issues such as redlining and job discrimination, as well as dilapidated housing built hastily after the burning. That had all given Ed some perspective, too. There were inequities everywhere he looked, and the opportunities for every person in Greenwood were hemmed in by those disparities. Instead of simply finding a way to carve his own slice of profit off a broken system, he realized he’d be better off wielding a weapon to combat the system itself: the Oklahoma Eagle.

The Eagle’s mission went beyond simply reporting the news or the arm’s-length objectivity that white journalism of the era so often aspired to. The newspaper advocated for Black manufacturing jobs during World War II, helped recruit Martin Luther King, Jr. for a visit to Greenwood in 1960, and later protested the destructive impacts of urban renewal on the neighborhood. It was an organ of the community that it covered, intertwined with Greenwood’s fate in a way that few newspapers are. The purpose was clear from the day that Ed added a new mission statement to the front page, appearing right below the nameplate every single week: “We Make America Better When We Aid Our People.”

Even as businesses shuttered and families were forced to leave Greenwood over the decades, the Eagle and the Goodwins remained. But by 2020, the rhythms of the neighborhood had changed. Cars and semis barrel over Greenwood Avenue on an interstate overpass that cleaved the community in half in 1967. The monotonous clanging of bolts driving into steel beams marked the steady rise of luxury apartments occupying more and more of the area. In the modern era, Greenwood Avenue came alive only when the Tulsa Drillers, a minor league baseball team, took the field on land once owned by Black people—some of it once owned by the Goodwins themselves, in fact.

The Eagle held strong in a refurbished auto garage just east of Greenwood Avenue, on the same block J.H. Goodwin surveyed on his first trip to Tulsa in 1913. The family had never taken stock of exactly how many editions of the Eagle they had published since Ed bought the paper in 1937, but an issue every week for eighty-four years equaled about 4,368 editions. Jet and Ebony and the Tulsa Tribune didn’t last as long, and most of the publications that did were acquired by corporations with headquarters far removed from the communities they covered.

Jim Goodwin, one of Ed’s sons, took on the mantle of Eagle co-publisher in the 1980s, fending off bankruptcies and the steady hollowing-out of Greenwood and surrounding Black neighborhoods. On a cold January morning in 2020, his office desk was littered with a brown accordion folder stuffed with case files, a Catholic pamphlet titled Cathedral News, a bronze statue of a blind angel balancing the scales of justice, and a funeral program for Luther Elliot, Jr., an old friend who has just recently died.

Jim also kept more private documents close by his side. Sliding open a desk drawer, he fished out a bundle of old papers, the pages turned yellow with age. SENIOR ESSAY, JAMES O. GOODWIN, June 1961, is written in typescript on the front. Jim began to read, and the cacophony of the new Greenwood outside slowly faded away.

“On a hillside several decades ago stood a burning cross. Hundreds of jubilant men, all members of the Ku Klux Klan had gathered around it. Two days earlier, they had mercilessly plundered and destroyed 50 percent of the Negro community. Now they converged upon a burning cross in celebration of victory. Behind them was a trail of blood and two million dollars in property damage…

The burning cross symbolized all their hatred for the negro and emblemized the white supremacist doctrine. It so controlled them that as the flame grew into one massive blaze, also the single taunts of hate blended into the thunderous roar of a mob.”

Three generations of the Goodwin family at their country estate, Willow Lake Farm, in the 1970s

Three generations of the Goodwin family at their country estate, Willow Lake Farm, in the 1970s

Before the history books and documentaries and HBO adaptations, Jim described, in vivid detail, the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He grew up referring to this dark history as a riot. More recently the term massacre had come into favor. But when he stopped to reflect on the magnitude of the destruction, and the dark motivation at the heart of it, he thought pogrom—an organized massacre of a particular ethnic group—might be the most apt description.

Jim’s words arced far back into the past, but they also stretched into the future. They warned against the vagaries of mob violence and white supremacy, of actions and ideologies that Americans want to bury in the past but that have metastasized in recent years, like a resurgent cancer. “Here I am now, from age twenty to age eighty,” Jim said, “grappling with the same issue.” He leaned back in his chair and stroked his white, closely cropped beard. At his age, the future was no longer a mystery; he could hear the echoes of the past in today’s news clarions, see the well-worn currents of history in the chaotic stream of current events. The U.S. felt more bound to its history than it ever had before.

America’s darkest memories and its most inspiring mythologies both route their way down Greenwood Avenue, through the very land Jim had always called home. But this is a city and a country all too eager to bury its past, to drown out the story of what happened here with interstate traffic, construction crews, and the din of an easygoing day at the ballpark. The whispers of the departed grow fainter with each passing day, as the arbiters of so-called justice patiently eye the hour glass. But their understanding of time is backwards.

An untreated wound doesn’t heal as the years go by; it festers. An unpaid debt is not wiped from the books; it accrues interest. Greenwood’s ancestors, the ones who witnessed its creation and its cataclysm, must all eventually go silent. Yet their voices still stir in the voices of their descendants—and finally, people are listening.

“I’m saying to the mayor and everyone else, you cannot pave over history,” Jim says. “No matter what you do, the history of Greenwood will be forever known.”

Adapted from Victor Luckerson’s new book Built from the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street

(Time).

Prosecutor: Gunman in Pittsburgh synagogue massacre harbored 'malice and hate' for Jews.

PITTSBURGH (AP) — Prosecutors on Tuesday described how a heavily armed suspect barged into a Pittsburgh synagogue and shot every worshiper he could find in the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history.

Robert Bowers’ federal trial got underway more than four years after the shooting deaths of 11 worshipers at the Tree of Life synagogue.

Twelve jurors and six alternates — chosen Thursday after more than 200 candidates were questioned over a month — are hearing the case. They include 11 women and seven men.

“The depths of the defendant’s malice and hate can only be proven in the broken bodies” of the victims and “his hateful words,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Soo C. Song said during her opening statement.

Some of the survivors dabbed tears, while Bowers, seated at the defense table, showed no reaction.

The defense was expected to present its opening statement before the prosecution began calling witnesses.

Bowers, 50, could face the death penalty if convicted of some of the 63 counts he faces in the Oct. 27, 2018, attack, which claimed the lives of worshipers from three congregations who were sharing the building, Dor Hadash, New Light and Tree of Life. Charges include 11 counts each of obstruction of free exercise of religion resulting in death and hate crimes resulting in death.

Members of the three congregations arrived at the courthouse in a school bus and entered together.

Prosecutors have said Bowers made antisemitic comments at the scene of the attack and online.

In proceedings before and during juror questioning, the defense has done little to cast doubt on whether Bowers was the gunman and has instead focused on preventing his execution.

Bowers, a truck driver from the Pittsburgh suburb of Baldwin, had offered to plead guilty in return for a life sentence, but federal prosecutors turned him down. Bowers’ attorneys also recently said he has schizophrenia and brain impairments.

As an indication that the guilt-or-innocence phase of the trial seems almost a foregone conclusion, Bowers’ lawyers spent little time during jury selection asking how potential jurors would come to a verdict.

Instead, they focused on the penalty phase and how jurors would decide whether to impose the death penalty in a case of a man charged with hate-motivated killings in a house of worship. The defense probed whether potential jurors could consider factors such as mental illness or a difficult childhood.

The families of those killed are divided over whether the government should pursue the death penalty, but most have voiced support for it.

The trial is taking place in the downtown Pittsburgh courthouse of the U.S. District Court for Western Pennsylvania, presided over by Judge Robert Colville, an appointee of former President Donald Trump.

Prosecutors are expected to tell jurors about incriminatory statements Bowers allegedly made to investigators, an online trail of antisemitic statements that they say shows the attack was motivated by religious hatred, and the guns recovered from him at the crime scene, where police shot Bowers three times before he surrendered.

They indicated in court filings that they might introduce autopsy records and 911 recordings during the trial, including recordings of two calls from victims who were subsequently shot to death. They have said their evidence includes a Colt AR-15 rifle, three Glock .357 handguns and hundreds of cartridge cases, bullets and bullet fragments.

Bowers also injured seven people, including five police officers who responded to the scene, investigators said.

In a filing earlier this year, prosecutors said Bowers “harbored deep, murderous animosity towards all Jewish people.” They said he also expressed hatred for HIAS, founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, a nonprofit humanitarian group that helps refugees and asylum seekers.

Prosecutors wrote in a court filing that Bowers had nearly 400 followers on his Gab social media account “to whom he promoted his antisemitic views and calls to violence against Jews.”

The three congregations have spoken out against antisemitism and other forms of bigotry since the attack. The Tree of Life congregation also is working with partners on plans to overhaul its current structure, which still stands but has been closed since the shootings, by creating a complex that would house a sanctuary, museum, memorial and center for fighting antisemitism.

The death penalty trial is proceeding three years after now-President Joe Biden said during his 2020 campaign that he would work to end capital punishment at the federal level and in states that still use it. His attorney general, Merrick Garland, has temporarily paused executions to review policies and procedures, but federal prosecutors continue to vigorously work to uphold death sentences that have been issued and, in some cases, to pursue new death sentences at trial. (Associated Press).

The first Memorial Day.

The Washington Post headline below 👇 is too iffy for me. Fascinating story.

Black people may have started Memorial Day. Whites erased it from history.

On May 1, 1865, thousands of newly freed Black people gathered in Charleston, S.C., for what may have been the nation’s first Memorial Day celebration. Attendees held a parade and put flowers on the graves of Union soldiers who had helped liberate them from slavery.

The event took place three weeks after the Civil War surrender of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and two weeks after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. It was a remarkable moment in U.S. history — at the nexus of war and peace, destruction and reconstruction, servitude and emancipation.

The event took place three weeks after the Civil War surrender of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and two weeks after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. It was a remarkable moment in U.S. history — at the nexus of war and peace, destruction and reconstruction, servitude and emancipation.

But the day would not be remembered as the first Memorial Day. In fact, White Southerners made sure that for more than a century, the day wasn’t remembered at all.

It was “a kind of erasure from public memory,” said David Blight, a history professor at Yale University.

In February 1865, Confederate soldiers withdrew from Charleston after the Union had bombarded it with offshore cannon fire for more than a year and began to cut off supply lines. The city surrendered to the Union army, leaving a massive population of freed formerly enslaved people.

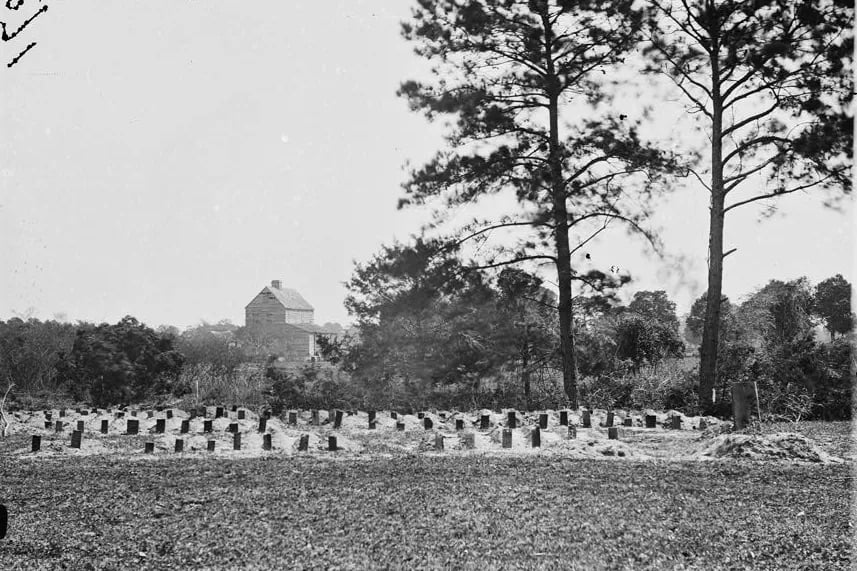

Also left in the wake of the Confederate evacuation were the graves of more than 250 Union soldiers, buried without coffins behind the judge’s stand of the Washington Race Course, a Charleston horse track that had been converted into an outdoor prison for captured Northerners. The conditions were brutal, and most of those who had died succumbed to exposure or disease.

In April, about two dozen of Charleston’s freed men volunteered to disinter the bodies and rebury them in rows of marked graves, surrounded by a wooden, freshly whitewashed fence, according to newspaper accounts from the time.

Then, on May 1, about 10,000 people — mostly formerly enslaved people — turned out for a memorial service that the freed people had organized, along with abolitionist and journalist James Redpath and some White missionaries and teachers from the North. Redpath described the day in the New-York Tribune as “such a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina or the United States never saw before.”

The day’s events began around 9 a.m. with a parade led by about 2,800 Black schoolchildren, who had just been enrolled in new schools, bearing armfuls of flowers. They marched around the horse track and entered the cemetery gate under an arch with black-painted letters that read “Martyrs of the Race Course.” The schoolchildren proceeded through the cemetery and distributed the flowers on the gravesites.

Other attendees entered the cemetery with even more flowers, as the schoolchildren sang songs including “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “John Brown’s Body.”

“When all had left,” Redpath wrote, “the holy mounds — the tops, the sides, and the spaces between them — were one mass of flowers, not a speck of earth could be seen; and as the breeze wafted the sweet perfume from them, outside and beyond, to the sympathetic multitude, there were few eyes among those who knew the meaning of the ceremony that were not dim with tears of joy.”

The dedication ended with prayers and Bible verses from local Black ministers, followed by speeches from Union officers and Northern missionaries, a picnic on the racecourse and drills by Union infantrymen, including some African American regiments. The observance didn’t end until sundown.

And then, Blight said, the event was forgotten. Not right away — but within a few decades, any recollection persisted merely as rumor, in verbal anecdotes.

The reason, he said, is that “by the middle and end of Reconstruction, the Black folks of Charleston were not creating the public memory of that city.”

The portrayal of the Civil War and its aftermath was controlled in the South by groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Ladies’ Memorial Association, as well as Confederate veterans, Blight said.

“The Daughters of the Confederacy were the guardians of that narrative,” said Damon Fordham, an adjunct professor of history at The Citadel, a military college in Charleston. “And much of that was skewed toward the Confederate point of view.”

Blight chronicled the 1865 Charleston ritual in his 2001 book “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory,” based on evidence that Fordham helped him uncover. Blight had been researching the book in 1999, in an archive of the Houghton Library at Harvard University, when he found a collection of papers written by Union veterans that contained a description of the May 1, 1865, events in Charleston.

If the description was accurate, Blight said, he knew that “that event in Charleston deserves its own full commemoration, just because of the poignancy of it, the sheer scale of it.”

But first he had to corroborate it. One of the first places he contacted was the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture at the College of Charleston. “I called up the curator there,” Blight recalled, “and I said, ‘I just found this in a collection of veterans materials. Have you ever heard of this story?’ And the guy said, ‘No. That never happened.’”

The “guy” was Fordham, who at the time was a graduate student at the college and a research assistant at Avery. Despite his doubts, Fordham knew the center had microfilm of the Charleston Courier, a daily newspaper from that time, so he checked it.

“About two hours later, he called me back, and he said, ‘Oh my God, here it is,’” Blight said. It was a Courier article from May 2, 1865, “describing this extraordinary parade on the old planters’ racecourse.”

Blight went on to find more proof, including an illustration of the fenced cemetery that was published in Harper’s Weekly in 1867. “Pretty soon I had all these sources that no one had ever bumped into, so one thing kept leading to another,” he said. “But even people in Charleston said, ‘No, never heard of it.’ That shows the power of the erasure of public memory over time.”

In the book, Blight describes a 1916 letter written by the president of the Ladies’ Memorial Association in Charleston, replying to an inquiry about the May 1, 1865, parade. “A United Daughters of the Confederacy official wanted to know if it was true that blacks and their white abolitionist friends had engaged in such a burial rite,” he wrote. “Mrs. S.C. Beckwith responded tersely: ‘I regret that I was unable to gather any official information in answer to this.’”

In the 1880s, the bodies of the Union soldiers, the “Martyrs of the Race Course,” were exhumed and moved to Beaufort National Cemetery. The horse track closed shortly after that, and the 60 acres of land became Hampton Park, named for Wade Hampton III, a Confederate general and Charleston native who became governor of South Carolina in 1876. Hampton enslaved nearly 1,000 people before the war, and his governorship was supported by the Red Shirts, a White paramilitary group that violently suppressed the Black vote.

By the end of the century, no vestige of the racecourse, the cemetery or the 1865 parade remained.

More spring graveside memorials followed the one in Charleston. Several occurred in towns across the country in the spring of 1866, and many of these places — such as Columbus, Miss., whose commemoration became annual — claim to have held the original Memorial Day observance. Officially, the nation recognizes Memorial Day as having started in Waterloo, N.Y.

In Charleston, the freed people didn’t have the power to develop an annual tradition after 1865. But the city now recognizes itself, regardless, as the holiday’s birthplace.

“On May 1, 1865, a parade to honor the Union war dead took place here,” reads a state historical marker erected in Hampton Park in 2017. “The event marked the earliest celebration of what became known as ‘Memorial Day.’” (The Washington Post).

_______________________________