Tuesday, October 7, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

Today is the 2nd anniversary of the barbaric attack by Hamas on Israel.

No words.

But the horrors of Hamas do not justify the

mass killing of the people of Gaza by Netanyahu.

Trump’s Shutdown continues.

Shutdown, Day 6: The two parties remain locked in a standoff with no end in sight.

The Supreme Court refused to hear the Appeal from Ghislaine Maxwell.

Supreme Court Rejects Appeal From Ghislaine Maxwell.

The Supreme Court on Monday declined to hear an appeal of the criminal conviction of Ghislaine Maxwell, the longtime associate of Jeffrey Epstein.

The court’s action ends Ms. Maxwell’s attempt to overturn her conviction, meaning her only chance of an early release from prison is likely to be clemency from President Trump, with whom she used to socialize in the Florida and New York party scenes.

Ms. Maxwell is currently serving a 20-year prison sentence after being convicted in 2021 on federal charges related to facilitating the crimes of Mr. Epstein. He died in 2019 in what was ruled a suicide while awaiting trial on sex-trafficking charges.

Federal prosecutors have opposed her release.

Trump may act.

NOW - Trump says he'll "speak to the DOJ" about pardoning Ghislaine Maxwell. pic.twitter.com/kBZ3uacSyr

— Disclose.tv (@disclosetv) October 6, 2025

One more thing.

Do you hear echos of Trump’s “some very fine people on both sides” about Charlottesville in 2017? 👇

https://x.com/atrupar/status/19753022800322234Where are we in the battle against Trump’s attempt to impose martial law in major American Blue Cities?

Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek, Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker. Both Oregon and Illinois are suing the Trump administration in federal court over the possible deployment of the National Guard to their states.

[Illinois.]

A federal judge on Monday declined to block the deployment of National Guard units to Illinois, a mobilization that the state’s governor, JB Pritzker, labeled an “unconstitutional invasion” by the federal government, even as President Trump threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to bypass court battles and send in the troops.

The judge’s ruling in Illinois, which allows the Trump-ordered deployment to move ahead for now, came as a military official said 200 troops from the Texas Guard were headed to Illinois. They are expected to be deployed in the Chicago area by Tuesday or Wednesday. A similar effort to send Texas troops to Portland, Ore., has been blocked for now.

[Illinois and Oregon]

Officials in Illinois and Oregon fought an intensifying legal battle on Monday to block President Trump’s deployment efforts, and both sides engaged in an increasingly caustic war of words, with the Trump administration accusing protesters of engaging in insurrection and officials in Chicago accusing federal forces of attacking their residents without provocation.

Illinois sued the president on Monday morning to stop the deployment of troops, and Mr. Pritzker said that the state would use every lever at its disposal to fight the administration. “Their plan all along has been to cause chaos, and then they can use that chaos to consolidate Donald Trump’s power,” he warned in an afternoon news conference.

Here’s what else to know:

Oregon appeal: The Trump administration asked an appeals court to let it send troops from California or Texas to Portland, Ore., despite a federal judge’s order late Sunday blocking deployments from any state to the city. The judge was appointed by Mr. Trump.

Chicago actions: Mayor Brandon Johnson said he would establish “ICE-free zones” to prevent federal agents from staging operations in Chicago without a warrant. And officials in Broadview, Ill., issued an executive order restricting protests at a federal immigration facility to daytime hours to protect demonstrators from attacks by federal agents.

“Like a war zone”: President Trump on Monday described Chicago as a crime-ridden “war zone.” In a legal filing, his administration depicted Portland as a hotbed of violence and chaos, and described protests as attempts to overthrow the government. Conditions on the ground in both cities do not match those descriptions, though clashes have turned more intense, and sometimes violent, since Mr. Trump’s escalation.

In his effort to deploy the military in major cities, President Trump threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act, which would grant him emergency powers to deploy troops, as a means to bypass court rulings that have blocked the deployments. “We have an Insurrection Act for a reason,” Trump said. “If I had to enact it, I’d do that if people were being killed and courts were holding us up, or governors or mayors were holding us up.” (New York Times)

I’m on the Senate floor to condemn the Trump Administration’s decision to send National Guard troops to Chicago. https://t.co/HV4lpcZYnx

— Senator Dick Durbin (@SenatorDurbin) October 6, 2025

Is CBS going the way of Fox News?

WHAT WILL BARI WEISS DO TO CBS NEWS?

A change in leadership at the network has been seen as part of an effort to appease Donald Trump. But there may be other motivations.

In 2018, Bari Weiss, then an opinion columnist at the Times, wrote about the so-called Intellectual Dark Web, a loose “alliance of heretics” who were “making an end run around the mainstream conversation.” Adherents were photographed for the article in literally dark settings: glowering out from under an umbrella, perched amid mossy branches, standing half-obscured by bushes. Though they came from different ideological backgrounds, Weiss wrote, these figures—including Eric Weinstein, the managing director of Peter Thiel’s venture-capital fund, who had “half-jokingly” coined the movement’s name; Joe Rogan, an “MMA color commentator and comedian” with a hugely popular podcast; and Jordan Peterson, the already best-selling philosopher—felt they had been ostracized by legacy media outlets in the Trump era for voicing reasonable opinions.

These positions ran the gamut: arguing that free speech was under attack, believing in biological gender differences, thinking that forcing Muslim women to “live their lives inside bags is wrong.” Many in the group were building channels of their own. Weiss was sympathetic, but did not quite commit to fellowship. “Having been attacked by the left,” she wrote, “I know I run the risk of focusing inordinately on its excesses—and providing succor to some people whom I deeply oppose.”

Weiss wrote this article at something like the midpoint of her Times journey. When Donald Trump won the Presidency in 2016, she was at the Wall Street Journal; the morning after the election, she sobbed at her desk, and realized that she felt too liberal for the paper and needed to leave.

In 2017, she joined the Times, where this was definitely not a problem—but, after three years of being consistently derided (not least over the I.D.W. piece), she quit, and, on the way out, publicly accused her colleagues of cowering before the orthodoxies of Twitter and “bullying” her for committing “Wrongthink.” She has said that she voted for Joe Biden in 2020.

But, by the beginning of this year, she was sounding more conciliatory about Trump, dismissing her prior anguish as “Trump derangement syndrome.” “There were two things, I think, that I didn’t know in that moment when I was crying at my desk,” she explained: “the kind of illiberalism that was born out of the reaction” to Trump, and the fact that he would enact “a lot of policies that I agreed with.”

Along the way, Weiss founded the Free Press, a news site hosted on Substack—where it is the best-selling politics offering, with roughly a million and a half subscribers, some eleven per cent of whom pay—that sits somewhere between the center and the right, without “center-right” feeling like a consistently accurate label. This was Weiss’s own end run around mainstream institutions, and the site has come to be seen, at least by its fans, as an expression of her “pro-Israel and anti-woke worldview—not to mention her broadly shit-kicking anti-establishment disposition,” as Puck’s Dylan Byers recently put it. Weiss’s many critics would dispute that she was ever “anti-establishment.”

Either way, she is indisputably back in the mainstream: the occasion for Byers’s piece was to report that David Ellison, the son of the billionaire Larry Ellison, and the freshly minted chairman of Paramount Skydance, the parent company of CBS News, was planning to put Weiss in charge of that outlet’s “editorial direction”; this morning, she was formally unveiled as its editor-in-chief. (Notably, she will report directly to Ellison.) The Free Press is coming along, too, with Ellison’s company having acquired it at a reported valuation of a hundred and fifty million dollars. According to a press release, Weiss will continue to lead the Free Press, but the site will “maintain its own independent brand and operations.”

Weiss arrives at a moment that feels almost existential for CBS News, whose owners have been widely and credibly accused, in recent months, of kowtowing to Trump. This summer, Paramount settled a risible lawsuit that Trump filed over edits to a “60 Minutes” segment about Kamala Harris that had displeased him. Shortly thereafter, the Federal Communications Commission approved Paramount’s merger with Ellison’s Skydance. More or less everyone saw these developments as connected; Stephen Colbert said—on CBS—that the settlement was a “big fat bribe,” right before his show was cancelled. (Executives denied any quid pro quo, and cited financial motivations for cutting Colbert.) Brendan Carr, the F.C.C. chair, did publicly welcome Skydance’s “commitment to make significant changes at the once storied CBS broadcast network,” including measures to “root out” what he described as bias. Paramount Skydance also promised to appoint an ombudsman to oversee CBS News, and soon did, tapping Kenneth Weinstein, a right-wing think-tank type and recent G.O.P. donor. Last month, the network said it would no longer edit interviews on its Sunday show “Face the Nation,” after the Administration complained about cuts to a pre-recorded sitdown with Kristi Noem, the Secretary of Homeland Security.

In a recent profile of Weiss in the Guardian, the progressive journalist David Klion predicted that she would act as an “ideological commissar” at CBS, helping to further “enforce compliance” with the White House line. Others share the fear that a Trumpified Weiss is storming the citadel of objective journalism. Some version of this dynamic may well play out—as I see it, neither Ellison nor Weiss has accumulated enough benefit of the doubt for us to trust any promises to the contrary. But a maga-fied CBS isn’t a guarantee. The story is a bit murkier than Manichaean talk of stormers and citadels.

One could say that the Free Press focusses on the excesses of the left to an extent that provides succor to people Weiss opposes, or, at least, used to oppose. The right-wing activist Christopher Rufo, who is often helpfully explicit about his aims, has described the site as a “beautiful off-ramp” for center-left élites whom he is trying to “radicalize” into “a kind of defector class.”

But the Free Press is not Breitbart, and Weiss is not Steve Bannon. Last year, the Free Press polled its own staff and found its support was split, somewhat evenly, between Trump, Kamala Harris, and neither; since Trump returned to power, the site has rebuked his Administration for nakedly threatening Jimmy Kimmel, to name one example. Last week, Byers wrote that Weiss is “more consistently centrist than her critics care to acknowledge,” and that “it’s quite likely that her first brush with controversy will come when her free speech absolutism” puts CBS in conflict with Trump. Given the crêpe-paper quality of Trump’s skin, you don’t have to think that Weiss is a centrist or a free-speech absolutist (and I certainly don’t believe she is either) to see this as a plausible collision.

Trump’s return to power is, at minimum, essential context for Ellison’s takeover of CBS News and hiring of Weiss, in ways that are specific—Trump’s recent pressure campaign against the network and the role of his regulators in approving the Skydance deal; his apparent closeness to the Ellison family—and in the more general sense that he has exerted a rightward gravitational pull on the concept of what it means for media to be “mainstream.” (The denizens of the Intellectual Dark Web, it’s safe to say, would not be depicted hiding in a forest today.) Ellison will, perhaps, need to stay in the Administration’s good graces as he seeks approval for other deals, including a possible bid for Warner Bros. Discovery, which owns CNN. Even if Ellison seems to care more about Warner Bros.’ entertainment properties—and Paramount’s, for that matter—than he does about news, it’s plausible that he sees hiring Weiss as throwing a bone to Trump while maintaining deniability in politer company. (Again, she’s not Bannon.) Publicly, Ellison has pledged to prioritize “truth” and “trust” at CBS, and said that he won’t politicize the network. At least some staffers say they already view this promise as worthless.

And yet it’s easy to imagine a world in which Harris won, and Ellison acquired CBS and hired Weiss anyway, to similar howls from the left. (His deal for the network was struck in the summer of 2024.) Though CBS might pivot toward Trump under her leadership, it’s a safer bet that her biggest impact will be on the stories that seem to animate her most—campus protests and Israel—whether or not Trump is involved with them. Ellison’s family is close to Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s Prime Minister, and Ellison was reportedly attracted to Weiss’s pro-Israel politics. (Not that the pair’s presence will invent tensions over Israel at CBS; prior to Ellison’s takeover, Shari Redstone, Paramount’s controlling shareholder, repeatedly intervened to disparage editorial decisions that she felt were insufficiently sympathetic to the country’s cause.)

Ultimately, Weiss appears to be beloved of very powerful people who are distressed by the rise of wokeness, and who for some reason see themselves as “besieged outsiders,” as The Nation’s Jack Mirkinson argued recently. To read a profile of Weiss is to be slapped around the face by the names of élite admirers; those now include the Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett and the Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, whose Saturnalian wedding Weiss attended in Venice this year. It’s often fair to describe such figures as pro-Trump, but not always, and I’ve previously argued that Bezos’s recent behavior—at least as expressed through the rightward tilt of the op-ed page at the Post, which he owns—has been driven more by a mix of self-interest and the self-mythologizing that Mirkinson describes than any doctrinaire commitment to Trump. The G.O.P. pollster Frank Luntz told the Times last year that Weiss “doesn’t just speak to the 1 percent” but to “the one-hundredth of 1 percent. And they’ll listen.” Ellison fits this description, and then some. He probably didn’t need the pretext of Trump to listen, or to act.

Some of the coverage of Weiss’s hiring at CBS has highlighted the apparent gulf between her opinionated, fairly small-scale digital-media business and the “quintessential traditional” TV behemoth that she is about to inherit. Various articles have cited the towering legacies of the CBS anchors Edward R. Murrow, who has been lionized for taking on McCarthyism, and Walter Cronkite, who would famously sign off from the “Evening News” with the line, “And that’s the way it is.” Some staffers at CBS have suggested that they will give Weiss a chance, but others have compared her to Michael Scott, and predicted that she will quickly be chewed up and spat back out. “Is Bari Weiss considered objective or a journalist?” one source asked rhetorically, in an interview with the Independent. “Cronkite and Murrow would absolutely not think she is and would have tossed her out of the newsroom inside an hour.”

Maybe so—and a coming wave of insider stories attesting to Weiss’s difficulties in asserting her authority strikes me as the most inevitable outcome of this affair. But the mythology of CBS’s storied journalistic past belies a more nuanced reality. (Some of Murrow’s own colleagues thought that he was late to the battle with McCarthy, for instance.) And, while there is, to be sure, a difference between straight news and overt opinion, the line where those genres meet is fuzzy, and inevitably subjective. Even if CBS staffers (rightly) see the Free Press as opinionated, it might not see itself that way; indeed, the site claims simply to be covering the world the way it is, when mainstream newsrooms have abandoned that role. (Already, in the press release announcing her appointment, Weiss promised to make CBS News “the most trusted news organization of the 21st Century.”) This isn’t to say that everything is relative. But the truth rarely just reveals itself. The choices journalists make in seeking it inevitably inform the stories they tell.

Sometimes, the truth is viciously fought over. Trump and Weiss have certainly long been in combat mode, even if they might not always be on the same team. When Trump took on CBS earlier this year, its journalists did not back down from the stories they wanted to tell, either: one segment on “60 Minutes,” for example, quoted a source likening Trump’s intimidation of law firms to the behavior of a Mob boss, drawing another legal threat from the President; after Bill Owens, the show’s executive producer, quit, a correspondent said, bluntly, on air, that Owens felt he’d lost his independence from management amid the settlement and merger sagas. We’ll have to see what shape the fight takes from here. I don’t think that Trump has won just yet. I don’t think Weiss has, either. ♦︎ (New Yorker)

An overlooked hero.

Overlooked No More: Bessie Margolin, Lawyer Who Turned Workers’ Hopes Into Law

Her streak of Supreme Court victories, which began during the New Deal era, benefited millions of workers and continue to shape labor rights today.

Bessie Margolin around 1954 ascending the steps of the Supreme Court in Washington.Credit...U.S. Department of Labor, via Malcolm Trifon.

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

It was March 1945. Bessie Margolin, a Labor Department lawyer helping to defend New Deal reforms, stood before the United States Supreme Court to argue her first case. She was by all measures an oddity in those hallowed chambers: a woman in a predominantly male legal world, a Jew whose presence in pedigreed institutions was often scowled at, and a newcomer with an unconventional upbringing (she grew up in a Southern orphanage, and her first job involved peddling encyclopedias in Baton Rouge).

Opposite her was the patrician Joseph B. Ely, a former Massachusetts governor whose political roots ran nine generations deep. He had a preacher’s voice that lifted crowds to their feet at political rallies. And though he was a Democrat like Franklin D. Roosevelt, he hated the president’s efforts to enact wide-reaching economic, social and political reforms. A year earlier, he had tried to block Roosevelt’s nomination for an unprecedented fourth term as a way to curb his party’s leftward drift.

Now, as counsel to big industry, Ely was aiming to throttle a New Deal law known as the Fair Labor Standards Act, which gave the country a 40-hour workweek and a minimum wage and banned forms of child labor that were considered too dangerous for the underaged to handle. (The law was amended in 1963 to also protect against wage discrimination based on gender.)

Though Margolin was a neophyte to that political veteran, she unfurled all that she had in court: her wit, her silver tongue and her first-class ability to unknot legal complexities.

She won.

The court’s ruling in the case, Phillips, Inc. v. Walling, set a precedent for limiting corporate attempts to evade the fair labor law.

Margolin was “crisp in her speech and penetrating in her analyses,” Justice William O. Douglas, who witnessed all of her 24 Supreme Court arguments, wrote in his autobiography, “The Court Years: 1939 to 1975” (1980).

Margolin in 1954 with Stuart Rothman, a solicitor of the Labor Department.Credit...U.S. Department of Labor, via Malcom Trifon

Through a decades-long career defending the fair labor law in court, Margolin helped protect workers from abusive employers (preventing teenagers, for example, from having to lift 400-pound tubs of milk by hand crane) and ensured that laborers’ wages would cover incidental tasks like changing into a protective factory garment as part of a work shift.

Margolin in 1972 at her retirement celebration with Chief Justice Earl Warren. She had argued before him 15 times.Credit...U.S. Department of Labor, via Malcolm Trifon.

From 1939 to 1972, when she retired, her legal successes benefited tens of millions of workers. On her retirement, Chief Justice Earl Warren, before whom she argued 15 times, said Margolin had defended legislation that “would have been wholly inadequate without the implementation she forged in the courtrooms of our land.”

Bessie Margolin — her name was spelled Becy Margolyn on her birth certificate and later corrected — was born on Feb. 24, 1909 (some records say Feb. 25), in Brooklyn. She was the middle child of Harry and Rebecca (Goldschmidt) Margolin, who had fled religious persecution in Russia and resided briefly in New York before resettling their family in Memphis.

Harry Margolin in 1913 with his children, from left, Bessie, Jacob and Dora. Harry’s wife, Rebecca, had died the year before. He put the children in an orphanage. Credit...via Malcolm Trifon.

When Rebecca died of an illness in 1912, Harry, a traveling salesman, decided that Bessie and her siblings Dora and Jacob would be better off living at the Jewish Orphans’ Home in New Orleans, a prominent institution where Bessie was said to have flourished. Her teachers praised her for her verbal agility, and she was offered a scholarship to Tulane University when she was 16.

She graduated in 1930 with both a bachelor’s and a law degree, ranking second in her law class of otherwise all men.

Around this time, she faced a difficult choice between raising a family or embarking on a career. She chose the latter, turning down a marriage proposal from a peer at Tulane. (She never married, even turning down a proposal at age 72).

But she struggled to find professional work as a woman, and her Jewish background was an impediment as well. Before she was hired for a research position at Yale, her former dean at Tulane had to reassure the registrar in a letter that Margolin possessed “none of the characteristics that mark some of the people of that race as offensive.”

There were so few women in the legal profession in her day that Margolin’s comings and goings in the field could make headlines. This 1931 article in a New Orleans newspaper reported that she had been hired as a research assistant to an esteemed law professor at Yale University.Credit...New Orleans Times-Tribune.

Though she went on to impress Yale’s brightest minds and win a Sterling fellowship for a law doctorate in 1932 (the first woman to do so), private law firms closed their doors to her. She instead found opportunities in government.

After six years at a New Deal agency charged with lifting up the impoverished Tennessee Valley, Margolin joined the Labor Department under Secretary Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet; Perkins had helped pass the Fair Labor Standards Act. The legislation needed all the help it could get: Its predecessor, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, lasted only two years before the Supreme Court struck it down.

So few women were members of the bar in her day that Margolin’s mere appearance in a courtroom, never mind the Supreme Court, could generate headlines. One newspaper blared, “New Orleans Girl Represents U.S. at Hearing.” She nevertheless accumulated an impressive number of wins.

Of her 150 circuit court fights, Margolin won 114, said Marlene Trestman, who wrote “Fair Labor Lawyer” (2016), a biography of her. Seven of the cases she lost were reversed by the Supreme Court.

Margolin’s total of 24 arguments before the Supreme Court was a record that only two other women and relatively few men achieved in her time. She prevailed in all but three of the case she brought before the justices.

One circuit judge, in a note to a colleague in the 1970s, likened her tactics to a “game of judicial blackjack.”

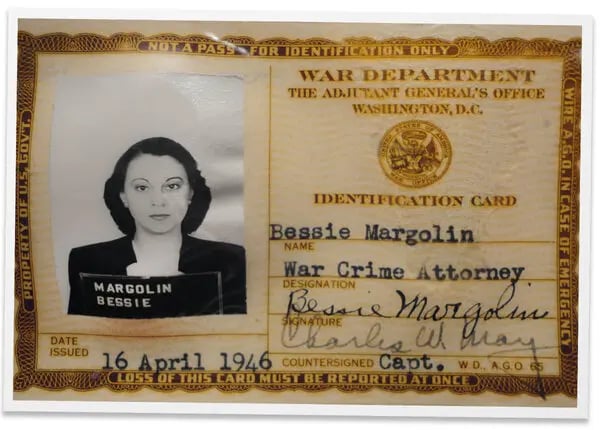

In 1946, after World War II, Margolin took a leave to participate in the Nuremberg war-crimes trials. There, in that bombed-out German city rife with the smell of decay, she was staggered to learn of the millions who had perished in Nazi extermination camps. It was “a profound awakening,” Trestman wrote.

In a letter to a colleague, Margolin wrote of the Nazis, “Human life apparently was the cheapest commodity on earth in their view and human dignity nonexistent.”

She helped build the legal scaffolding for some of the Nuremberg proceedings and helped recruit judges to preside over them.

In 1946, after World War II, Margolin took a leave to help build the legal scaffolding of the Nuremberg war-crimes trials. Credit...via Malcolm Trifon.

In April 1947, stateside once more, Margolin argued a Supreme Court case that would reshape how the country defined “employee” under labor law. The dispute involved Rutherford Food Corp.’s meat boners, the men and women who sheared carcasses to the bone. The company claimed that they were independent contractors, not employees, and that therefore they were not eligible for overtime pay.

Margolin countered that it was the nature of the work, not the contract, that defined an employee. Meat boners, integrated as they were into the factory’s production line, were employees, by and large, she argued.

The court sided with her.

Margolin in the 1950s. The Seattle Daily Times called her “the nation’s number one fighter for equal pay for women.”Credit...U.S. Department of Labor, via Malcolm Trifon.

More than eight decades later, the Department of Labor continues to revisit this debate. “One of the most important issues facing the D.O.L. is who is an employee subject to the Fair Labor Standards Act and who is an employee subject to its protections,” M. Patricia Smith, the solicitor of labor from 2010 to 2017, wrote in an email. “Many of her cases are the foundational cases that are always cited by D.O.L.”

In 1966, three years after President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act into law, Margolin took on a case against Wheaton Glass, a New Jersey company that made pharmaceutical wares. The lawsuit centered on the factory’s paying women less than men performing the job, as bottle packers.

After a nearly five-year fight, she won the women the same wages as the men, plus back pay for having earned about 22 cents less per hour than they had received (about $2.20 today).

In total, 300 equal pay lawsuits, filed in nearly every state, were won under Margolin’s watch, leading to roughly $4 million in back wages (about $40 million today).

She was, as The Seattle Daily Times called her in 1968, “the nation’s number one fighter for equal pay for women.”

Margolin’s high school senior yearbook picture from 1925. She was offered a scholarship to Tulane University when she was 16.Credit...Isidore Newman School Pioneer

Margolin died of a stroke on June 19, 1996, in Arlington, Va. She was 87. But her name and reputation continued to resound in legal circles — and at the Supreme Court.

Trestman recalled receiving a letter from one particular admirer who had just finished reading her biography. It was from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“Although Bessie’s path and mine have never crossed, I had heard much about her,” Ginsburg wrote. “Thank you for enabling me and legions of other lawyers to appreciate what a front-runner she was.” (Overlooked, New York Times)