Tuesday, June 10, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

All eyes on Los Angeles.

Brennan Center - The Posse Comitatus Act Explained

The Posse Comitatus Act bars federal troops from participating in civilian law enforcement except when expressly authorized by law. This 143-year-old law embodies an American tradition that sees military interference in civilian affairs as a threat to both democracy and personal liberty. However, recent events have revealed dangerous gaps in the law’s coverage that Congress must address.

What does the term “posse comitatus” mean?

In British and American law, a posse comitatus is a group of people who are mobilized by the sheriff to suppress lawlessness in the county. In any classic Western film, when a lawman gathers a “posse” to pursue the outlaws, they are forming a posse comitatus. The Posse Comitatus Act is so named because one of the things it prohibits is using soldiers rather than civilians as a posse comitatus.

What are the origins of the Posse Comitatus Act?

The Posse Comitatus Act was passed in 1878, after the end of Reconstruction and the return of white supremacists to political power in both southern states and Congress. Through the law, Congress sought to ensure that the federal military would not be used to intervene in the establishment of Jim Crow in the former Confederacy.

Despite the ignominious origins of the law itself, the broader principle that the military should not be allowed to interfere in the affairs of civilian government is a core American value. It finds expression in the Constitution’s division of power over the military between Congress and the president, and in the guarantees of the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments, which were in part reactions to abuses committed by the British army against American colonists.

Today, the Posse Comitatus Act operates as an extension of these constitutional safeguards. Moreover, there are statutory exceptions to the law that allow the president to use the military to suppress genuine rebellions and to enforce federal civil rights laws.

What does the Posse Comitatus Act say?

The Posse Comitatus Act consists of just one sentence: “Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.”

In practice, this means that members of the military who are subject to the law may not participate in civilian law enforcement unless doing so is expressly authorized by a statute or the Constitution.

Are all members of the military covered by the Posse Comitatus Act?

No, only federal military personnel are covered. While the Posse Comitatus Act refers only to the Army and Air Force, a different statute extends the same rule to the Navy and Marine Corps. The Coast Guard, though part of the federal armed forces, has express statutory authority to perform law enforcement and is not bound by the Posse Comitatus Act.

Members of the National Guard are rarely covered by the Posse Comitatus Act because they usually report to their state or territory’s governor. That means they are free to participate in law enforcement if doing so is consistent with state law. However, when Guard personnel are called into federal service, or “federalized,” they become part of the federal armed forces, which means they are bound by the Posse Comitatus Act until they are returned to state control.

What are the main statutory exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act?

There are many statutory exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act, but the most important one is the Insurrection Act. Under this law, in response to a state government’s request, the president may deploy the military to suppress an insurrection in that state. In addition, the Insurrection Act allows the president — with or without the state government’s consent — to use the military to enforce federal law or suppress a rebellion against federal authority in a state, or to protect a group of people’s civil rights when the state government is unable or unwilling to do so.

What are the constitutional exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act?

There are no constitutional exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act. The law allows only for express exceptions, and no part of the Constitution expressly empowers the president to use the military to execute the law. This conclusion is consistent with the law’s legislative history, which suggests that its drafters chose to include the language about constitutional exceptions as part of a face-saving compromise, not because they believed any existed.

This has not stopped the Department of Defense from claiming that constitutional exceptions to the law exist. The Department has long claimed that the Constitution implicitly gives military commanders “emergency authority” to unilaterally use federal troops “to quell large-scale, unexpected civil disturbances” when doing so is “necessary” and prior authorization by the president is impossible. In the past, the department also claimed an inherent constitutional power to use the military to protect federal property and functions when local governments could not or would not do so. The validity of these claimed authorities has never been tested in court.

What are the weak points in the Posse Comitatus Act?

Events in 2020 and 2021 have highlighted two loopholes in the Posse Comitatus Act. The first involves the District of Columbia National Guard. Unlike all other state and territorial National Guards, the DC Guard is always under presidential control. Despite this, the Department of Justice has for years asserted that the DC Guard can operate in a non-federal, “militia” status, in which it is not covered by the Posse Comitatus Act. By this interpretation, presidents can use the DC Guard for law enforcement whenever they choose.

Another weakness in the Posse Comitatus Act arises from the law that allows the National Guard to operate in “Title 32 status.” In Title 32 status, a middle ground between purely state operations and federalization, Guard personnel are paid with federal funds and may perform missions requested by the president, but they remain under state command and control. That means they are not subject to the Posse Comitatus Act, even though they are serving federal interests.

How have these loopholes in the Posse Comitatus Act been exploited?

In the summer of 2020, President Trump deployed the DC National Guard into Washington to police mostly peaceful protests against law enforcement brutality and racism. Simultaneously, over the objections of DC’s mayor, the administration asked state governors to deploy their own Guard personnel into Washington in Title 32 status, and 11 governors did so. Although these out-of-state forces were nominally under their governors’ control, it was later revealed that they were reporting up through the DC Guard’s chain of command for “coordination” purposes. That meant they were ultimately taking orders from the president. In this way, the Trump administration brought a large, federally controlled military force into Washington and used it for civilian law enforcement, all while skipping over the procedures in the Insurrection Act and evading the political costs of invoking it. That is exactly what the Posse Comitatus Act is meant to prevent.

Moreover, the deployment of non-federalized, out-of-state Guard forces into a jurisdiction without its consent represents another threat to the Posse Comitatus Act. When operating in Title 32 status, Guard forces are exempt from the Posse Comitatus Act because they are under state command and control. A key part of that control is the governor’s right to decline a particular federal mission. That right is meaningless if the president can simply approach a different governor and ask her to deploy her state’s Guard into the unwilling governor’s state. In this scenario, the cooperating governor becomes a fig leaf for the president to use the military as a police force anywhere in the country, free from the constraints of the Posse Comitatus Act.

How should the Posse Comitatus Act be reformed?

Congress should pass three reforms to help close these loopholes in the Posse Comitatus Act. First, it should transfer control over the DC National Guard from the president to the mayor of Washington. The president would still be able to take command of the DC Guard when necessary by federalizing it, but it would then be subject to the Posse Comitatus Act, just like all other federally controlled military forces.

Second, Congress should clarify that governors may not send their National Guard forces into another state or territory without the latter jurisdiction’s consent. This will stop future presidents who want to use the military domestically, but do not want to follow the laws established by Congress, from going from governor to governor until they find one who is willing to do their dirty work.

Third, Congress should enact a law clarifying that the Posse Comitatus Act applies to National Guard forces whenever they report through a federal chain of command, regardless of whether they have officially been called into federal service. This will ensure that form is not elevated over substance and will more fully realize the principle behind the law. (Brennan Center for Justice, published Oct. 14, 2021).

One more thing.

The Insurrection Act has not been invoked without a state request since 1965, when LBJ invoked it to protect civil rights marchers as they traveled from Selma to Montgomery AL.

Federalizing the California National Guard.

President Trump's Saturday night "memorandum" federalizing 2000 California National Guard troops is a tentative step toward abusing authorities for domestic use of the military, but a dangerous one.

From Steve Vladeck, Law professor, Georgetown University and editor and author of the Supreme Court newsletter, “One First.”

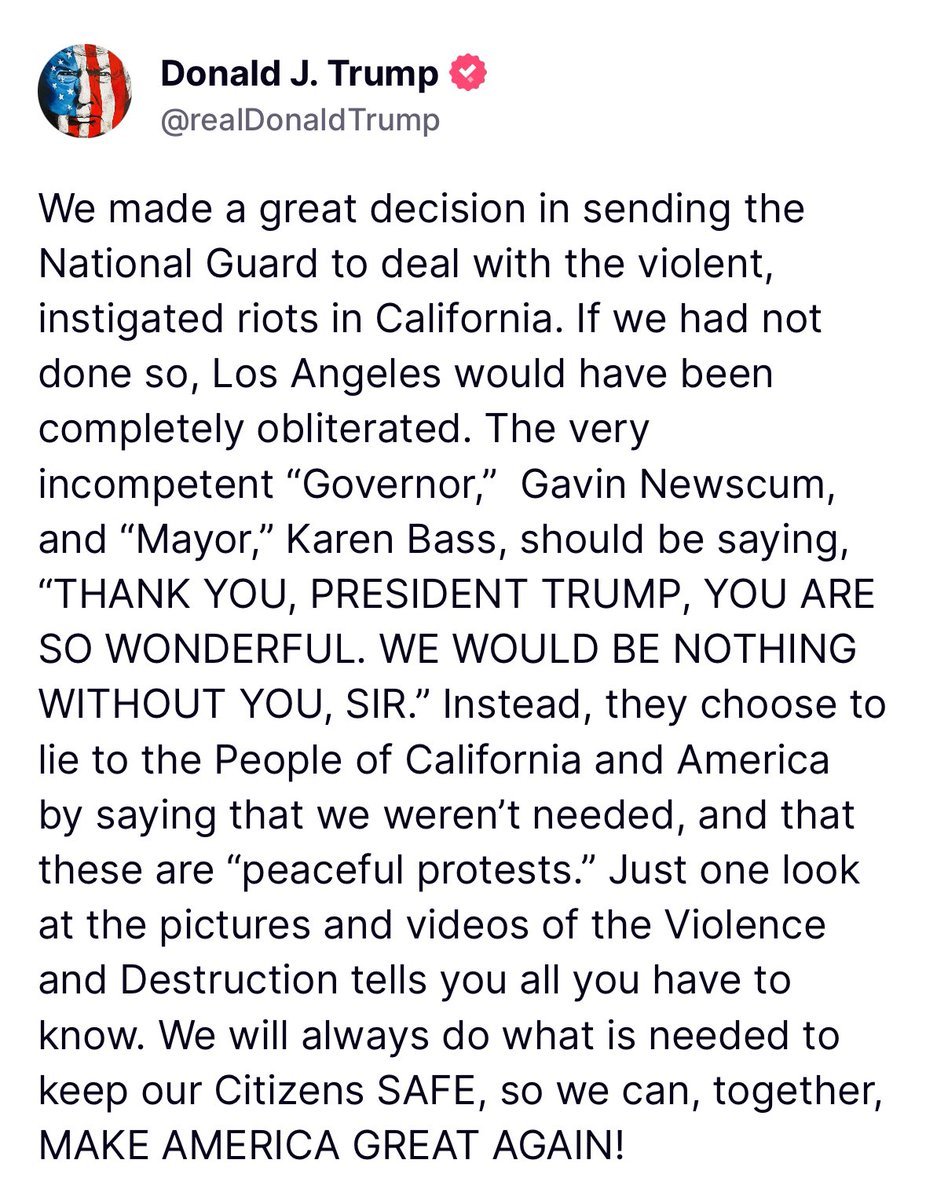

I wanted to put out an extra issue this evening in response to a “Presidential Memorandum” signed by President Trump, which federalizes 2000 members of the California National Guard and directs them to support Department of Homeland Security activities (i.e., ICE raids) in and around Los Angeles. All of this is in response to protests against those very ICE raids today that, in several cases, turned violent (with at least some evidence that the violence came principally from federal officers).

There are a lot of misunderstandings and misinformation out there about what Trump has and hasn’t done, and given that I’ve covered these topics before, it seemed worth a quick explainer on why this move is a big deal—but why it also is not as drastic an escalation (or abuse) as many had feared, at least not yet.

The TL;DR here is that Trump has not (yet) invoked the Insurrection Act, which means that the 2000 additional troops that will soon be brought to bear will not be allowed to engage in ordinary law enforcement activities without violating a different law—the Posse Comitatus Act. All that these troops will be able to do is provide a form of force protection and other logistical support for ICE personnel. Whether that, in turn, leads to further escalation is the bigger issue (and, indeed, may be the very purpose of their deployment). But at least as I’m writing this, we’re not there yet.

I. What Trump Did (and Didn’t) Do.

Back in April, I went into some detail on the key authorities authorizing (and limiting) domestic use of the military. In a nutshell, the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 generally bars domestic use of federal (but not state) troops for civilian law enforcement, but it has a couple of exceptions—the most well-known of which is the Insurrection Act. My April post goes into much more detail about the history, scope, and controversy surrounding the Insurrection Act (which has not been invoked by any President since 1992); the key point for present purposes is that President Trump has not invoked it here.

Instead, President Trump has federalized 2000 National Guard troops pursuant to 10 U.S.C. § 12406, which provides, among other things, that “when the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States . . . [he] may call into Federal service members and units of the National Guard of any State in such numbers as he considers necessary to . . . execute those laws.”1

As the brevity of this statute should make clear, this provision provides no additional substantive authority that the federal government did not already possess. There’s nothing these troops will be allowed to do that, for example, the ICE officers against whom these protests have been directed could not do themselves. And because of the Posse Comitatus Act, the reverse is not true; there is plenty that these troops cannot legally do that the ICE officers can (once they are federalized, National Guard troops become functionally indistinguishable from federal regulars for purposes of the Posse Comitatus Act).

Thus, nothing that the President did Saturday night would, for instance, authorize these federalized National Guard troops to conduct their own immigration raids; make their own immigration arrests; or otherwise do anything other than, to quote the President’s own memorandum, “those military protective activities that the Secretary of Defense determines are reasonably necessary to ensure the protection and safety of Federal personnel and property.”

On its face, then, the memorandum federalizes 2000 California National Guard troops for the sole purpose of protecting the relevant DHS personnel against attacks. That’s a significant (and, in my view, unnecessary) escalation of events in a context in which no local or state authorities have requested such federal assistance. But by itself, this is not the mass deployment of troops into U.S. cities that had been rumored for some time.

II. Why the Memorandum is Still Alarming…

That said, there are still at least three reasons to be deeply concerned about President Trump’s (hasty) actions on Saturday night:

First, there is the obvious concern that, even as they are doing nothing more than “protecting” ICE officers discharging federal functions, these federalized troops will end up using force—in response to real or imagined violence or threats of violence against those officers. In other words, there’s the very real possibility that having federal troops on the ground will only raise the risk of escalating violence—not decrease it.

Second, and related, there is the possibility that that’s a feature, and not a bug—that this is meant as a precursor, with federalizing a modest number of National Guard troops today invoked, some time later, as a justification for more aggressive responses to anti-ICE protests, including, perhaps invocation of the Insurrection Act. In other words, it’s possible that this step is meant to both be and look modest so that, if and when it “fails,” the government can invoke its failure as a basis for a more aggressive domestic deployment of troops. What happens in and around Los Angeles in the next few days will have a lot to say about this.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, as I wrote in April, “domestic use of the military can nevertheless be corrosive—to the morale of the troops involved, all of a sudden, in policing their own; to the relationship between local/state governments and the federal government; and to the broader relationship between the military and civil society.” Even uses of the military for relatively modest purposes can have those corrosive effects—especially where, as here, it seems so transparently in service of the President’s policy agenda, and not necessarily the need to restore law and order on the streets of America’s second largest city.

Even as someone who thinks the federal government has both the constitutional and statutory authority to override local and state governments when it comes to law and order (see, e.g., President Eisenhower sending troops into Little Rock to enforce Brown), it seems to me that there is something deeply pernicious about invoking any of these authorities except in circumstances in which their necessity is a matter of consensus beyond the President’s political supporters. The law may well allow President Trump to do what he did Saturday night. But just because something is legal does not mean that it is wise—for the present or future of our Republic.

A lot depends on what happens next. For now, the key takeaways are that there really isn’t much that these federalized National Guard troops will be able to do—and that this might be the very reason why this is the step the President is taking tonight, rather than something even more aggressive.

What happened to states’ rights, Kristi? pic.twitter.com/fih8a8J9u7

— MeidasTouch (@MeidasTouch) June 8, 2025

BREAKING: In shocking footage of Trump in 2020 that is now going viral, Trump says it’s against the law for a president to call in the National Guard on his own: “We can't call in the National Guard unless we're requested by a governor.” MAGA = 🤡.

— CALL TO ACTIVISM (@CalltoActivism) June 9, 2025

pic.twitter.com/cxYMfYEqay

See how quickly the National Guard can be called into action?...

— GingerSpice❄️💙 (@thedesertginger) June 8, 2025

What was the excuse January 6? pic.twitter.com/IaFGghP0RZ

Sunday.

Today in Paramount, California. Just another day in Trump’s America.

— Republicans against Trump (@RpsAgainstTrump) June 7, 2025

pic.twitter.com/rY4VdHkm6k

Tom Homan, the head of ICE, confirmed to NBC News that he would arrest Gov. Gavin Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass if they interfered with immigration raids. https://t.co/U3fpr1f1Ev

— HuffPost (@HuffPost) June 8, 2025

For Trump, This Is a Dress Rehearsal

Ordering the National Guard to deploy in Los Angeles is a warning of what to expect when his hold on power is threatened.

Yesterday, President Donald Trump ordered the National Guard to quell disorderly protests against immigration-enforcement personnel in Los Angeles. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth declared his readiness to obey Trump by mobilizing the U.S. Marines as well. These threats look theatrical and pointless. The state, counties, and cities of California employ more than 75,000 uniformed law-enforcement personnel with arrest powers. The Los Angeles Police Department alone numbers nearly 9,000 uniformed officers. They can surely handle some dozens of agitators throwing rocks, shooting fireworks, and impeding vehicular traffic.

If and when those 75,000 uniformed personnel feel overmatched by the agitators, California can request federal help of its own volition. When California has asked for needed federal help—during the wildfires earlier this year, for example—Trump has begrudged that help and played politics with it. Trump is now forcing help that the city and state do not need and do not want, not to restore law but to assert his personal dominance over the normal procedures to enforce the law.

But if the Trump-Hegseth threats have little purpose as law enforcement, they signify great purpose as political strategy. Since Trump’s reelection, close observers of his presidency have feared a specific sequence of events that could play out ahead of midterm voting in 2026:

Step 1: Use federal powers in ways to provoke some kind of made-for-TV disturbance—flames, smoke, loud noises, waving of foreign flags.

Step 2: Invoke the disturbance to declare a state of emergency and deploy federal troops.

Step 3: Seize control of local operations of government—policing in June 2025; voting in November 2026.

Some of Trump’s most fervent supporters urged him to follow this plan in November 2020. But in 2020, they waited too long—until after the votes were cast. Using the military to overturn an election already completed was too extreme a step for a Department of Defense headed by a law-respecting Cabinet secretary such as Mark Esper. Trump looked to the courts instead. Only after the courts disappointed him did Trump attempt violence, and then the only available tool of violence was the lightly armed mob he summoned to Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021. Harrowing as those events were, they never stood much chance of success: Without the support of any element of the military, Trump’s rioters could not impose the outcome Trump wanted.

But the methods Trump threatened in Los Angeles this weekend could be much more effective in November 2026 than the attempted civilian coup of January 2021.

If Trump can incite disturbances in blue states before the midterm elections, he can assert emergency powers to impose federal control over the voting process, which is to say his control. Or he might suspend voting until, in his opinion, order has been restored. Either way, blue-state seats could be rendered vacant for some time.

Precedents do exist for such action. In autumn 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant imposed martial law on counties in South Carolina to suppress Ku Klux Klan disturbances that were interfering with legal voting. More recently, the governor of the U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands delayed elections, including the election of the islands’ nonvoting delegate in the United States House of Representatives, after Saipan was struck by a super-typhoon in October 2018. In that same month, Trump himself claimed that a caravan of undocumented immigrants heading north toward the U.S. constituted a “national emergency” that would justify suspending civil authority and deploying the military in border states.

In his first term, Trump repeatedly talked more radically than he acted. He was usually constrained by his own appointees. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley rebuffed Trump’s suggestion during the George Floyd unrest that the military shoot protesters, which sufficed to dissuade Trump from upgrading the suggestion into a direct order.

But instead of Esper and Milley, the second Trump administration’s military is headed by a former talk-show host facing troubling allegations of heavy drinking and sexual misconduct. (He denies these claims.) Hegseth owes everything to Trump. The Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation are likewise headed by radical partisans with dubious records, abjectly beholden to Trump. This Trump administration is sending masked agents into the streets to seize and detain people—and, in some cases, sending detainees to a prison in El Salvador without a hearing—on the basis of a 1798 law originally designed to defend the United States against invasion by the army and navy of revolutionary France. The presidency of 2025 has available a wide and messy array of emergency powers, as the legal scholar Elizabeth Goitein has described.

Second-term Trump and his new team are avidly using those powers in ways never intended or imagined.

Since Trump’s return to the presidency in January, many political observers have puzzled over a seeming paradox. On the one hand, Trump keeps doing corrupt and illegal things. If and when his party loses its majorities in Congress—and thus the ability to protect Trump from investigation and accountability—he will likely face severe legal danger. On the other hand, Trump is doing extreme and unpopular things that seem certain to doom his party’s majorities in the 2026 elections. Doesn’t Trump know that the midterms are coming? Why isn’t he more worried?

This weekend’s events suggest an answer. Trump knows full well that the midterms are coming. He is worried. But he might already be testing ways to protect himself that could end in subverting those elections’ integrity. So far, the results must be gratifying to him—and deeply ominous to anyone who hopes to preserve free and fair elections in the United States under this corrupt, authoritarian, and lawless presidency. (David Frum, The Atlantic).

Reminder: In his first term, Trump ordered then Sec Def Esper to shoot protestors.

— Maine (@TheMaineWonk) June 8, 2025

Esper refused.

Gee I wonder how Hegseth would respond to that order…pic.twitter.com/wbEOTACsVP

https://x.com/gavinnewsom/status/1931565409440088175?s=61&t=I_Od53CbnPTsbLcD0baXPg

I have formally requested the Trump Administration rescind their unlawful deployment of troops in Los Angeles county and return them to my command.

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) June 8, 2025

We didn’t have a problem until Trump got involved. This is a serious breach of state sovereignty — inflaming tensions while… pic.twitter.com/tOtA5dcfxc

Big point that is being missed: without the insurrection act, the activated Guard troops are now federal army and cannot

— Adam Kinzinger (Slava Ukraini) 🇺🇸🇺🇦 (@AdamKinzinger) June 8, 2025

Do law enforcement.

Period

Newsom responds to Homan statement on possibly arresting him: He's a tough guy. Why doesn't he do that? He knows where to find me. Lay your hands off four year old girls that are trying to get educated. Come and arrest me. Let’s just get it over with tough guy. I don’t give a… pic.twitter.com/KbHAQalmUh

— Acyn (@Acyn) June 9, 2025

This is exactly what Donald Trump wanted.

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) June 9, 2025

He flamed the fires and illegally acted to federalize the National Guard.

The order he signed doesn’t just apply to CA.

It will allow him to go into ANY STATE and do the same thing.

We’re suing him.pic.twitter.com/O3RAGlp2zo

Monday.

https://x.com/harryjsisson/status/1932201719410143236

https://x.com/allenanalysis/status/1932224941572641093

The United States Marines are not trained to deescalate a protest. They are trained to fight & win wars.

— Maxwell Alejandro Frost (@MaxwellFrostFL) June 9, 2025

Trump is sending a Marine battalion to LA because he wants to escalate the situation to the point where people could get shot. https://t.co/TSWENQkqvs

New York Times Editorial

Trump Calling Troops Into Los Angeles Is the Emergency

The National Guard is typically brought into American cities during emergencies such as natural disasters and civil disturbances or to provide support during public health crises — when local authorities require additional resources or manpower. There was no indication that was needed or wanted in Los Angeles this weekend, where local law enforcement had kept protests over federal immigration raids, for the most part, under control.

Guard members also almost always arrive at the request of state leaders, but in California, Gov. Gavin Newsom called the deployment of troops “purposefully inflammatory” and likely to escalate tensions. It had been more than 60 years since a president sent in the National Guard on his own volition.

Which made President Trump’s order on Saturday to do so both ahistoric and based on false pretenses and is already creating the very chaos it was purportedly designed to prevent.

Mr. Trump invoked a rarely used provision of the U.S. Code on Armed Services that allows for the federal deployment of the National Guard if “there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the government of the United States.” No such rebellion is underway. As the governor’s spokesman and others have noted, Americans in cities routinely cause more property damage after their sports teams win or lose.

The last time this presidential authority was used over a governor’s objections was when John F. Kennedy overruled the governor of Alabama and sent troops to desegregate the University of Alabama in 1963. Supporters of states’ rights and segregation howled at the time and, in the usual corners, are still howling about it.

“To the extent that protests or acts of violence directly inhibit the execution of the laws, they constitute a form of rebellion against the authority of the government of the United States,” Mr. Trump wrote in an executive order, which is not a law but rather a memo to the executive branch. Yet the closest this nation has come to such a definition of rebellion was when Mr. Trump’s own supporters (whom he incited, then mostly pardoned) sacked the U.S. Capitol in 2021.

Past presidents, from both parties, have rarely deployed troops inside the United States because they worried about using the military domestically and because the legal foundations for doing so are unclear. Congress should turn its attention to such deliberations promptly. If presidents hesitate before using the military to assist in recovery after natural disasters but feel free to send in soldiers after a few cars are set on fire, the law is alarmingly vague.

Some legal experts note that Mr. Trump’s order goes even further. He “has also authorized deployment of troops anywhere in the country where protests against Immigration and Customs Enforcement are occurring or are likely to occur, even if they are entirely peaceful,” Liza Goitein, the senior director at the liberty and national security program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said in a social post. “That is unprecedented and a clear abuse of the law.”

There is, however, a long tradition of political protest making America stronger. And protesters will do nothing to further their cause if they resort to violence. But Mr. Trump’s order establishes neither law nor order. Rather it sends the message that the administration is interested in only overreaction and overreach. The scenes of tear gas in Los Angeles streets on Sunday underscored that point: that Mr. Trump’s idea of law and order is strong-handed, disproportionate intervention that adds chaos, anxiety and risk to already tense situations.

In 2020 it was Gen. Mark Milley, Defense Secretary Mark Esper and Attorney General William Barr who stepped in and overruled Mr. Trump in his pursuit of using active-duty troops to bring a violent end to demonstrations in Lafayette Square, much to the president’s frustration. His current attorney general, Pam Bondi, and secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth, have shown little reservation about potentially putting troops in a position where they might have to decide whether to follow an illegal or immoral order or unnecessarily endanger civilians. These are men and women who have sworn an oath to something more powerful than the current commander in chief: the Constitution. With little leadership, it appears they themselves will have to become students of the law and ethics that should guide their conduct. One can only hope they choose the right path.

The biggest challenge posed by Mr. Trump federalizing the National Guard is this: What’s the limiting principle? Could any president order federalized combat troops to enforce his or her whims? And ultimately, who and what is the U.S. military in service to — the American public or the president’s political agenda?

With this Trump White House, there’s a strong guarantee that the answer will not be sought in the rule of law, longstanding values or established norms. Instead, it will come down to — as it always does with this administration — whatever most serves the president’s interests and impulses.

(New York Times)

Trump deranged authoritarianism affecting the news media.

All eyes are on California but don’t turn your eyes from Trump’s newest attacks on the press.

The consequences of this go beyond Trump barring the @AP from the White House press pool. By this logic, a future Democratic president will be able to bar conservative media outlets that want to ask about, say, his advancing age or his son's business activities.

— Peter Baker (@peterbakernyt) June 7, 2025

Former 60 Minutes Host Scott Pelley continues his powerful warning and fight against Trump’s attack on a free press.

BREAKING: Former 60 Minutes Host Scott Pelley just hammered legacy media for allowing the rise of Trump. This is powerful. pic.twitter.com/Xg9jIbNUkX

— Democratic Wins Media (@DemocraticWins) June 8, 2025

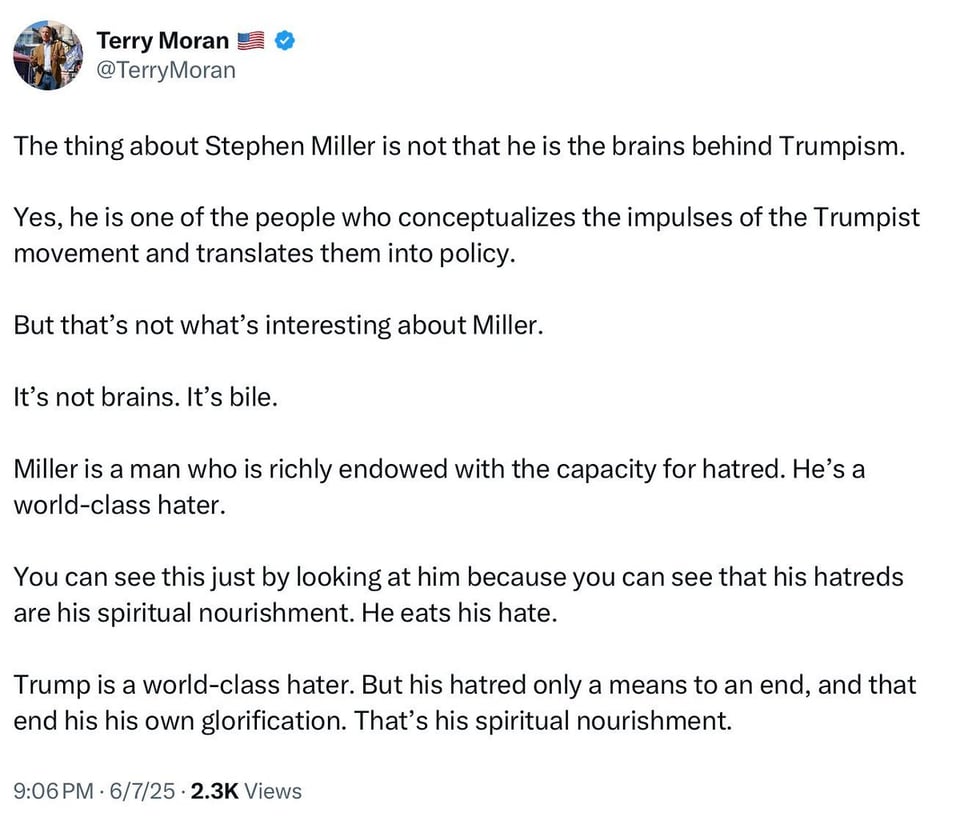

ABC caved immediately over the weekend when Trump attacked Terry Moran.

Terry Moran was suspended at ABC News after posting Stephen Miller is a "world-class hater."

— DonkConnects ♻️™ (@donkoclock) June 8, 2025

Drop a 💙 for @TerryMoran! Let's show him our support. pic.twitter.com/kxVmVvycFn

America’s strongman continues to get ready for his parade.